How To Sell Technology to the Government

A short framework for thinking about selling technology to DoD

Table of contents

- Intro

- Dev-Bur-Ops

- What About the Valley of Death?

- Bridging the Valley of Death

- Understanding Your (Real) Customer

- Building Runway

- Where Does Program Funding Come From?

- Shortcuts in GovCon

- You Can't Have Money Without a Contract

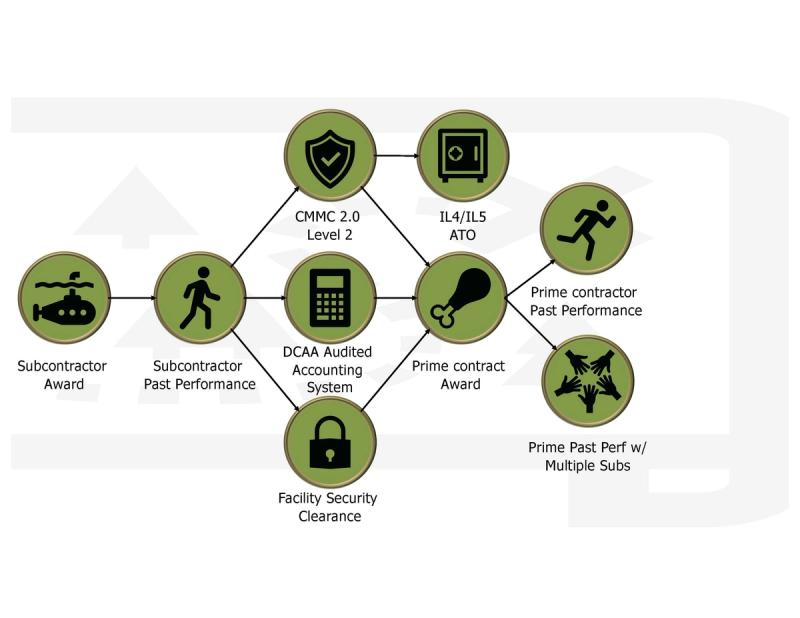

- Collect Them Merit Badges

- Subcontract Awards

- Subcontract Past Performance

- DCAA Audited Accounting System

- CMMC and NIST 800-171

- Facility Security Clearance

- Prime Contract Award

- IL4/IL5 ATO (for cloud products)

- Prime Past Performance

- Large Scale Projects with Multiple Subcontractors

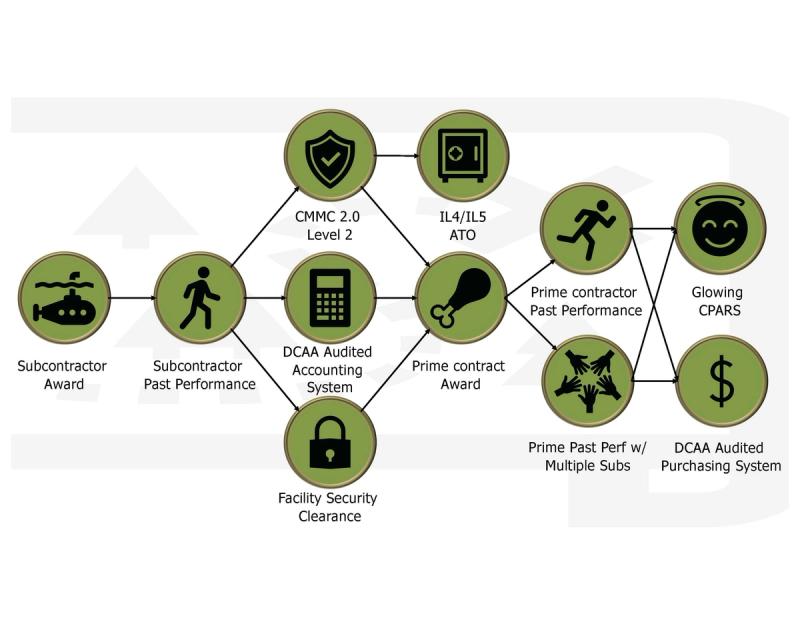

- Glowing CPARS

- DCAA Audited Purchasing System

- Bonus Badges

- MAC ID/IQ Contracts WITH TOs

- CPFF (Cost Plus Fixed Fee) Past Performance

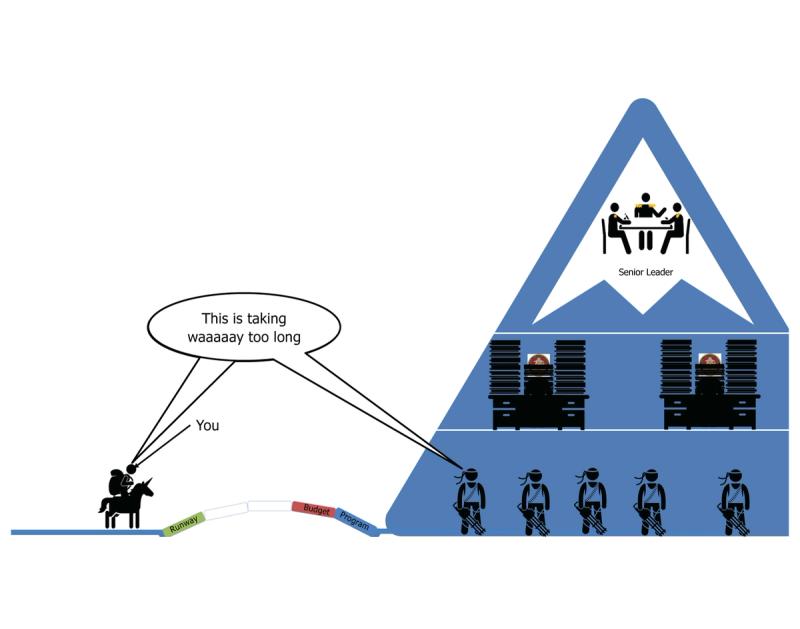

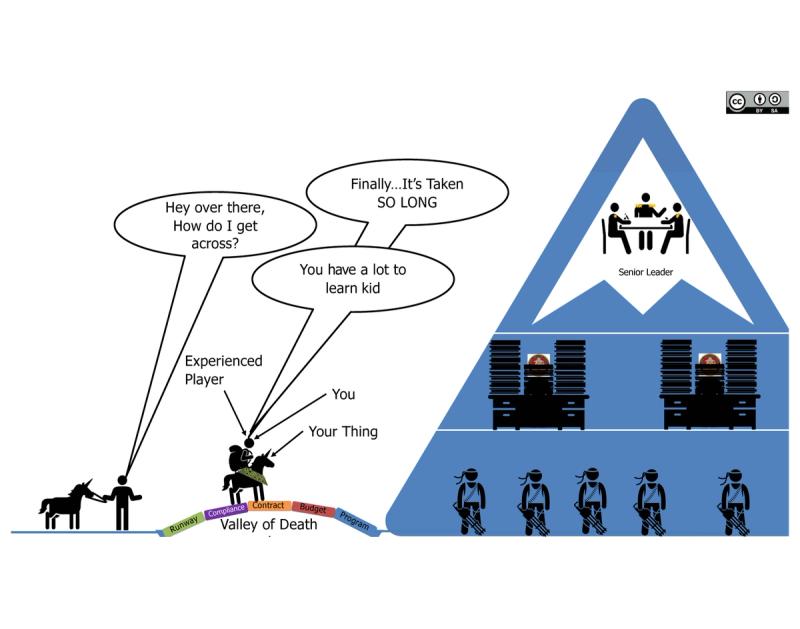

- This Is Going to Take SOOOO Long

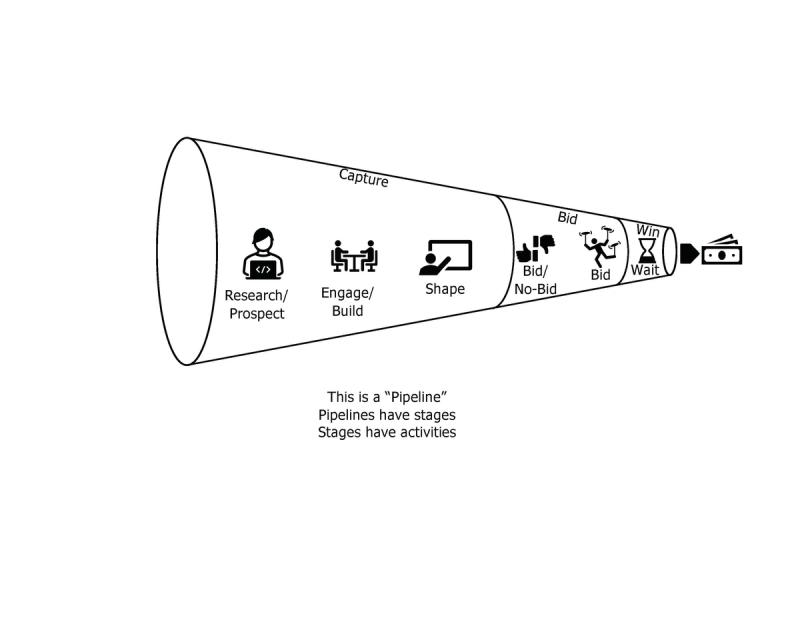

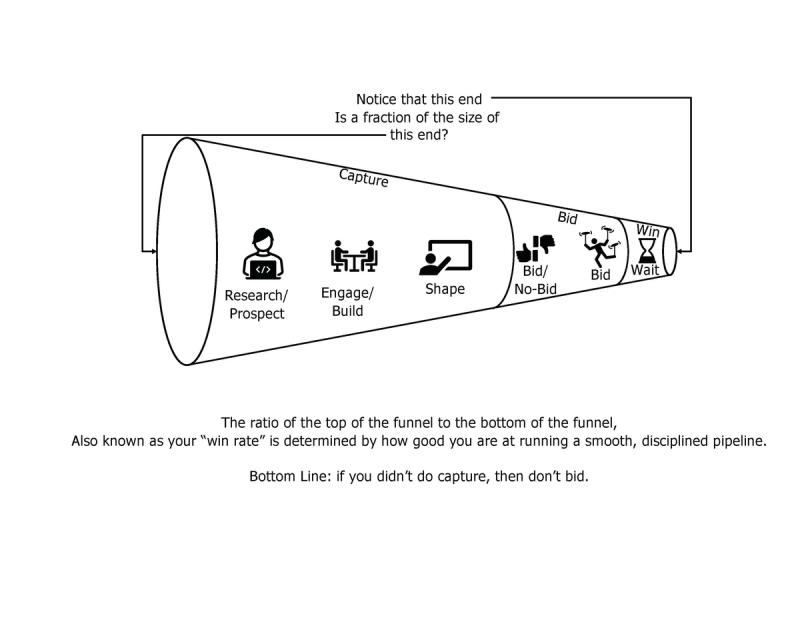

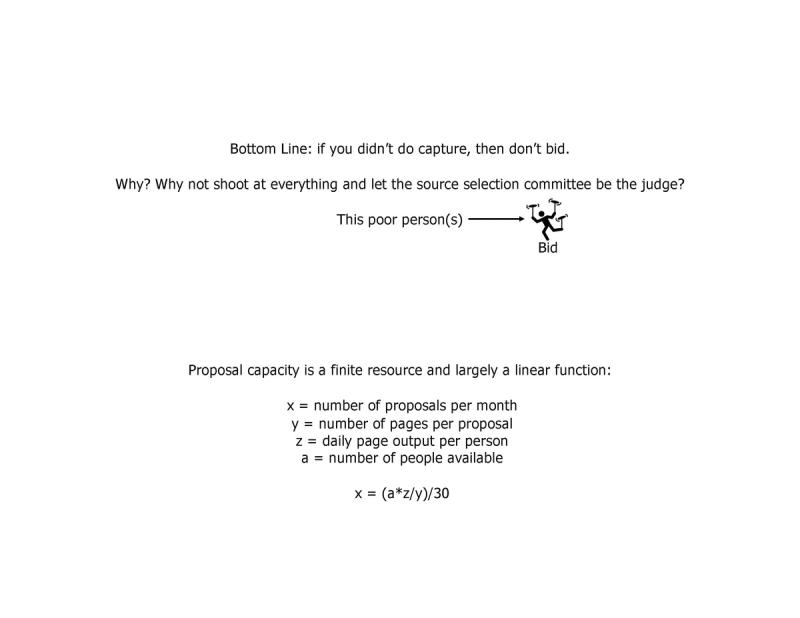

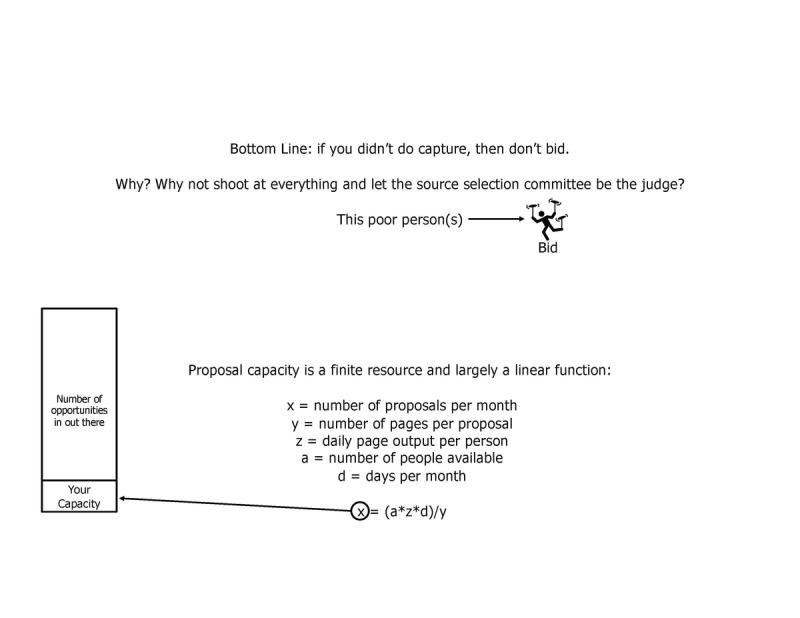

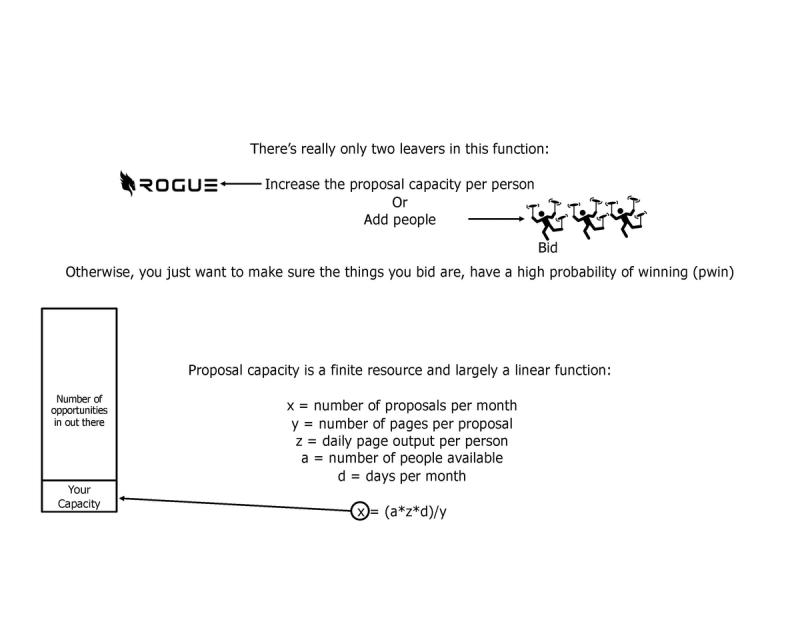

- Let's Talk About Sales

- VC: "How do I know if they're a unicorn or a Shetland pony?"

Intro

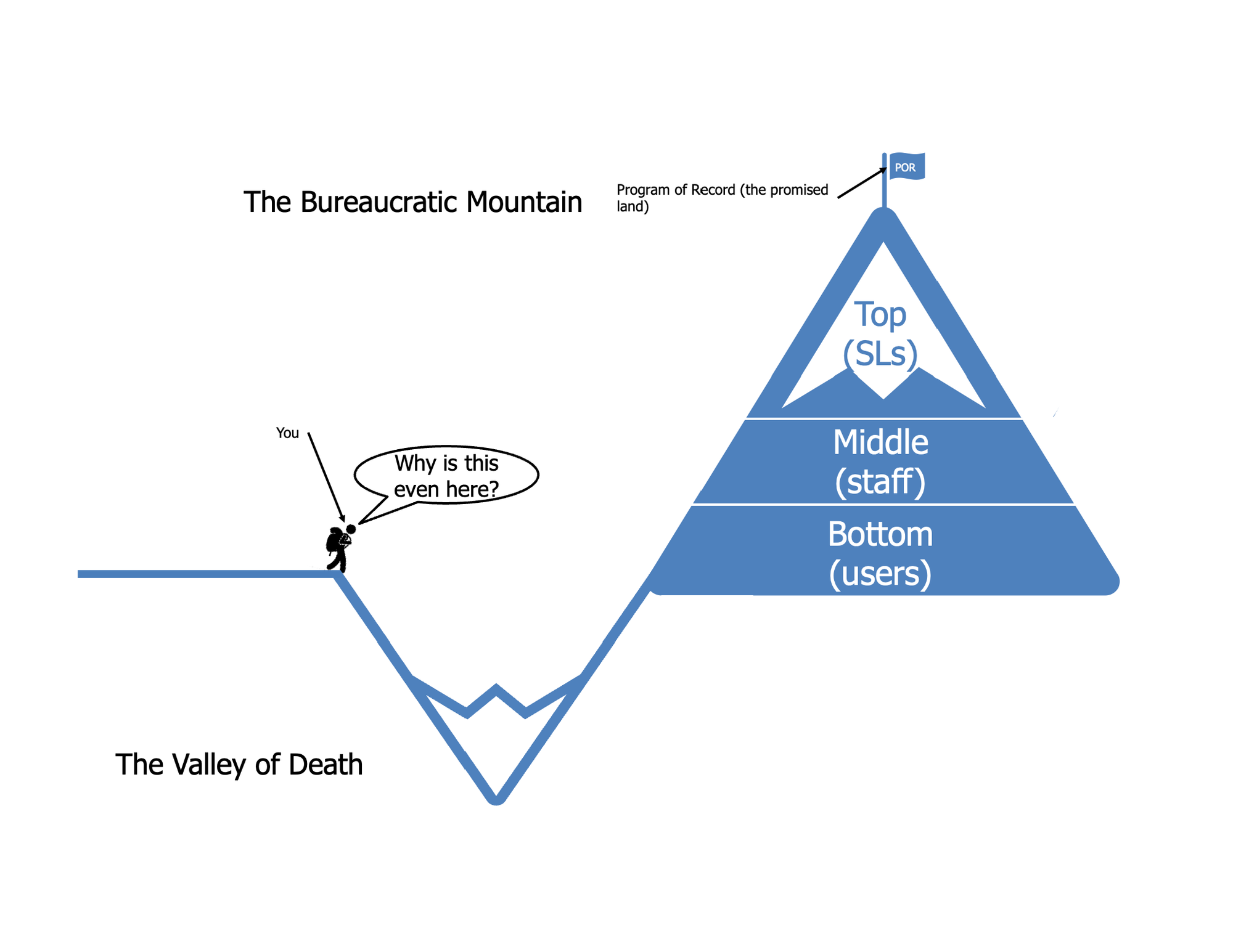

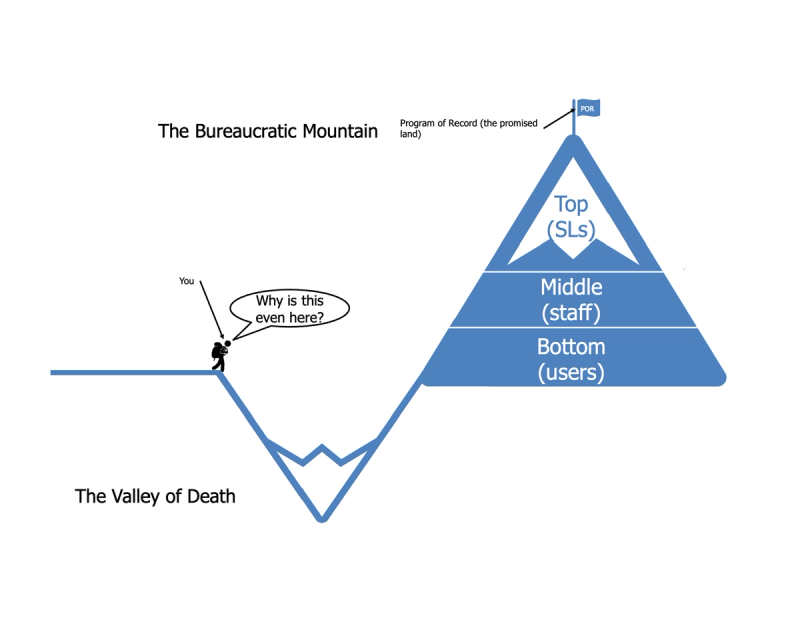

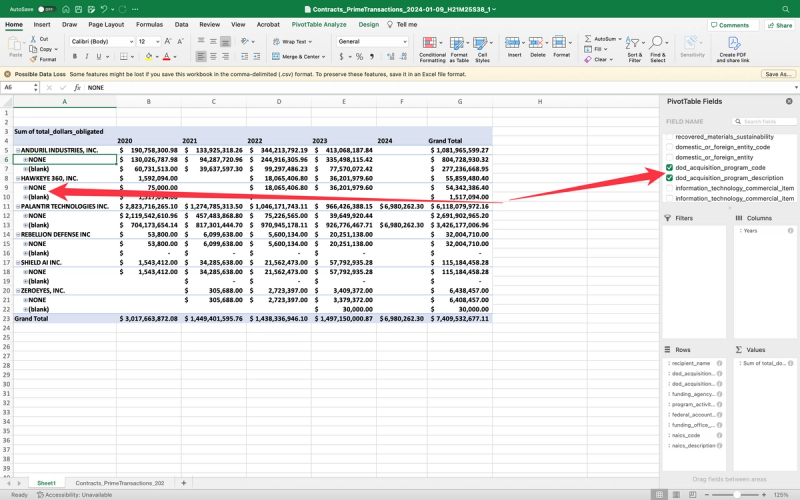

So you decided you want to sell to the Department of Defense. You have a new technological marvel that will revolutionize the way we fight and win wars. Great, you are now at the foot of a mountain.

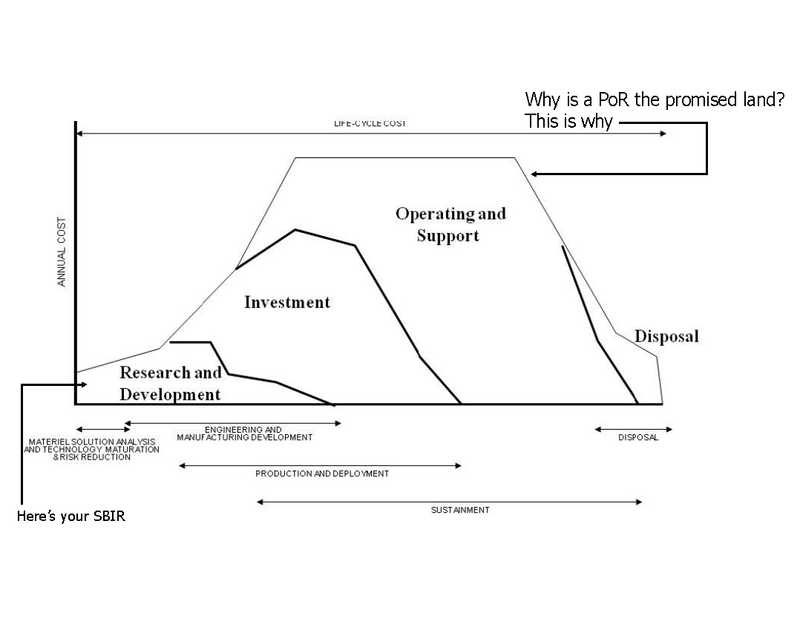

At the top of the mountain is inclusion in a Program of Record (PoR). Why do you want to be in a PoR?

1. That's where the (base-funded) budget dollars are. Without going into POM/BES and the rest, if you want a sustainable business that sells a decent amount of product, you want the dollars to come from a PoR

2. That's where the sustainment is. Sure, there's RDT&E investment dollars out there, someone might send you a few million to build a prototype and that's fine for your topline. But, if you want your widget to be issued to warfighters, if you want replacement parts to be ordered, you want any "Procurement" or "Operations and Maintenance" money (and trust me, you do) that all comes out of PoRs

3. That's where the moat is. It's a whole lot easier to sell 100 more units to a Program Manager who already has you written into their than to sell your first unit to a stranger.

Dev-Bur-Ops

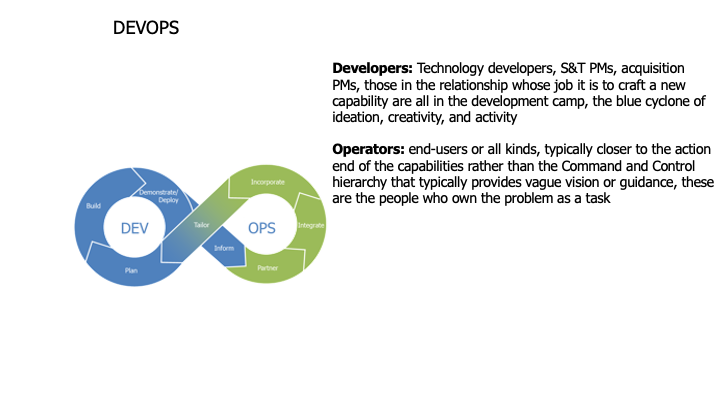

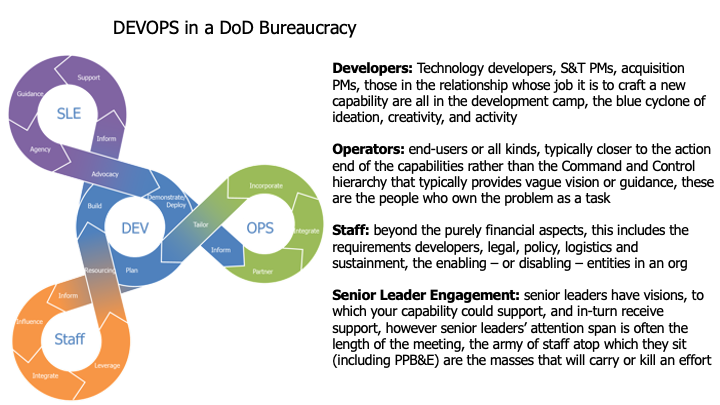

Selling tech to the civilian world is comparatively simple (simple, not easy), and there's a framework called DevOps where you find a customer, figure out what they need, and iterate through product-market fit and off to the promised land of sustainable growth, hockey sticks, etc.

We have these people in DoD too, they're called "end-users"; soldiers, sailors, airmen, marines, guardians who actually do the business of war. In general terms your thing will be used by them to do the business.

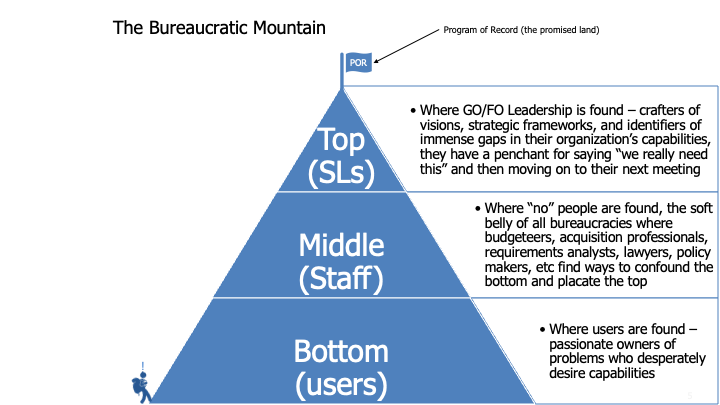

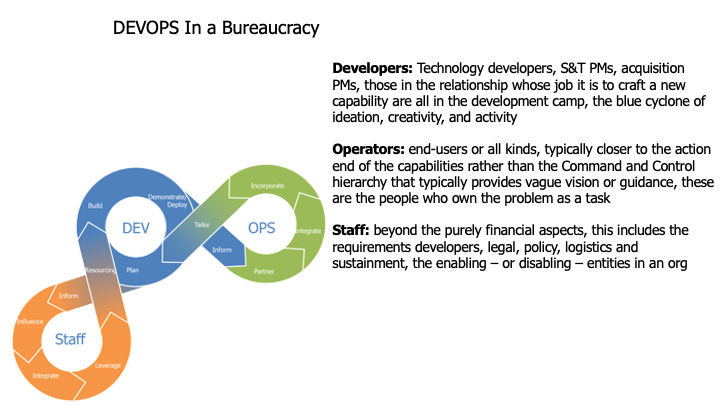

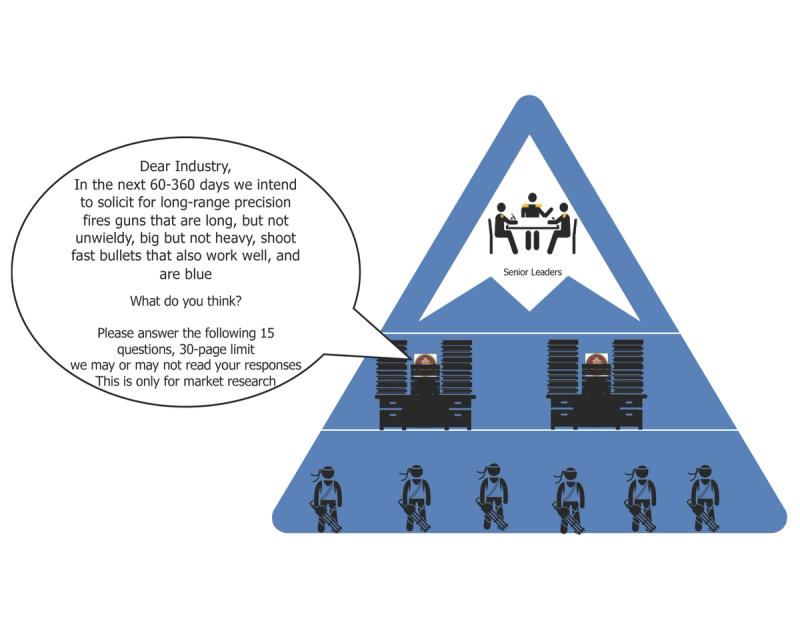

But you picked DefTech, which is neither simple nor easy, because DoD has a sprawling bureaucracy. You knew this getting into, but you probably didn't fully realize that the "staff" has a huge say in whether your customer ever gets to touch your product.

In DoD there's a third category of people who get a vote: senior leaders. They get a vote because your users inherently don't do anything unless they're told (this is the military after all.

So here you have Development-Bureaucracy-Operations, how you really successfully get tech into the hands of end users and into the coveted program of record.

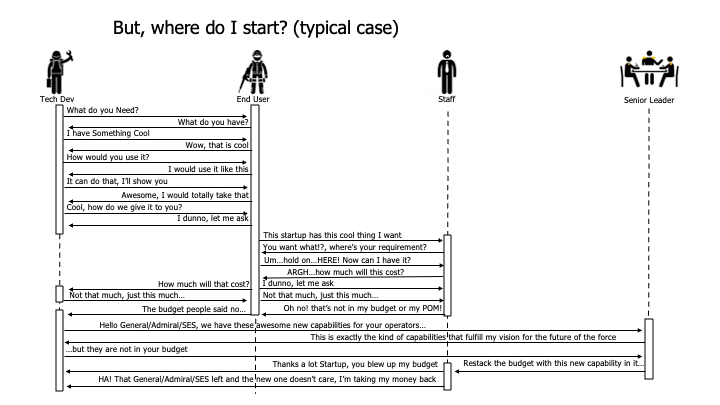

The way MOST developer folks do this (poorly) is they start with the end user, and they think that will work. There's good reason for this; developers are told by the DoD to "engage with us" and "talk to our end-users, they drive out requirements", which is true. So developers dutifully go to demo events, and expos, etc. End-users likewise reciprocate, they like new things, particularly those which promise to make their lives better. But there's a hitch: end-users don't BUY ANYTHING, the bureaucracy does.

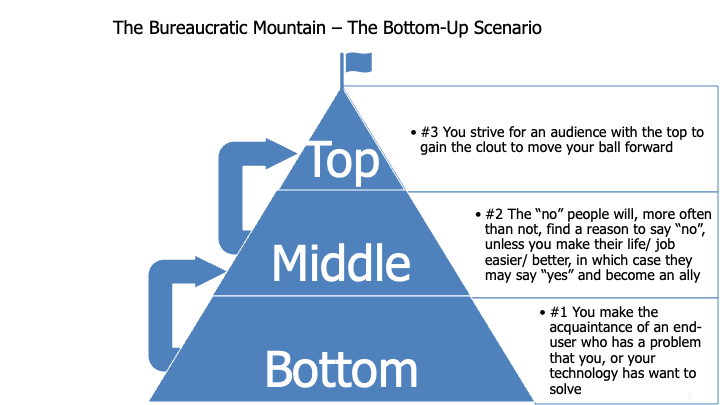

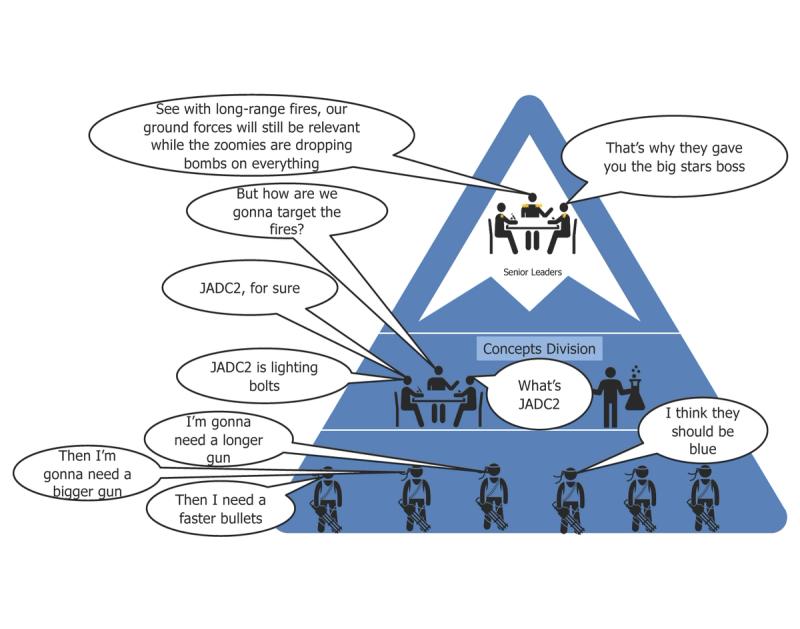

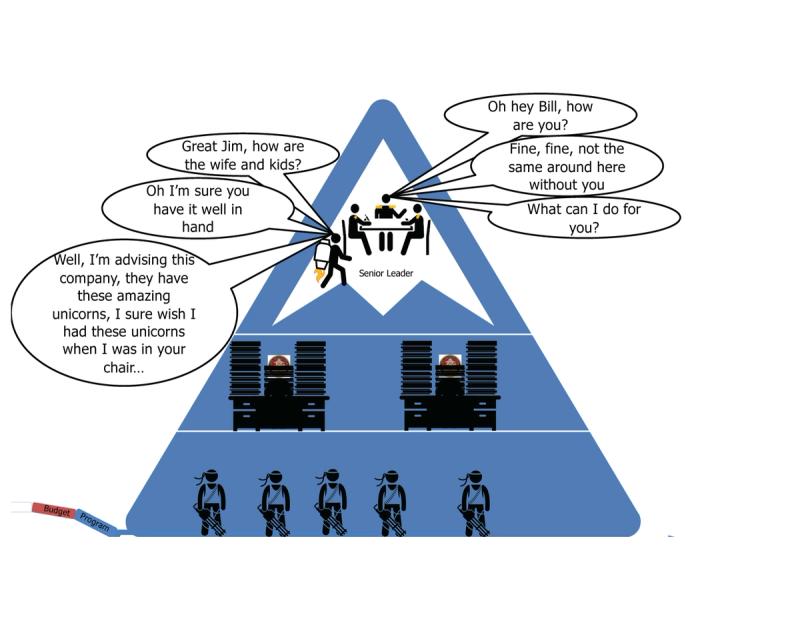

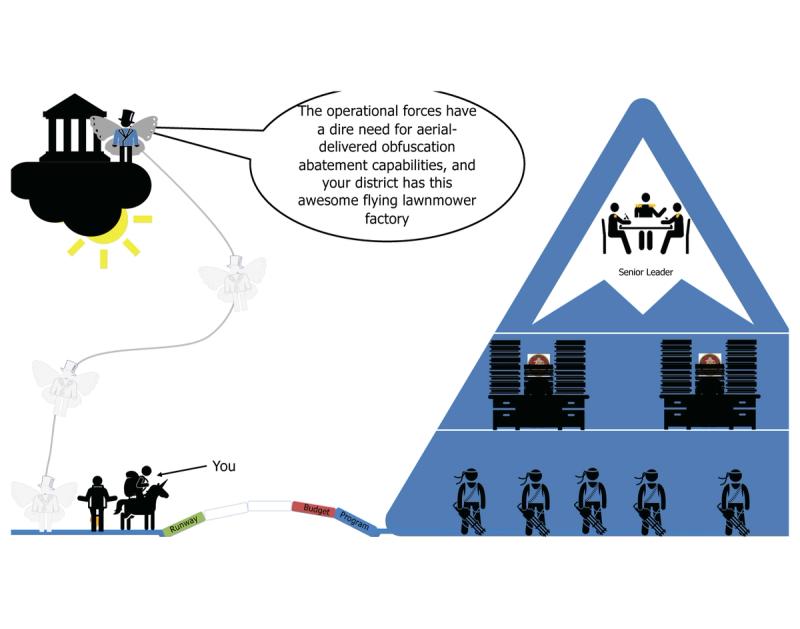

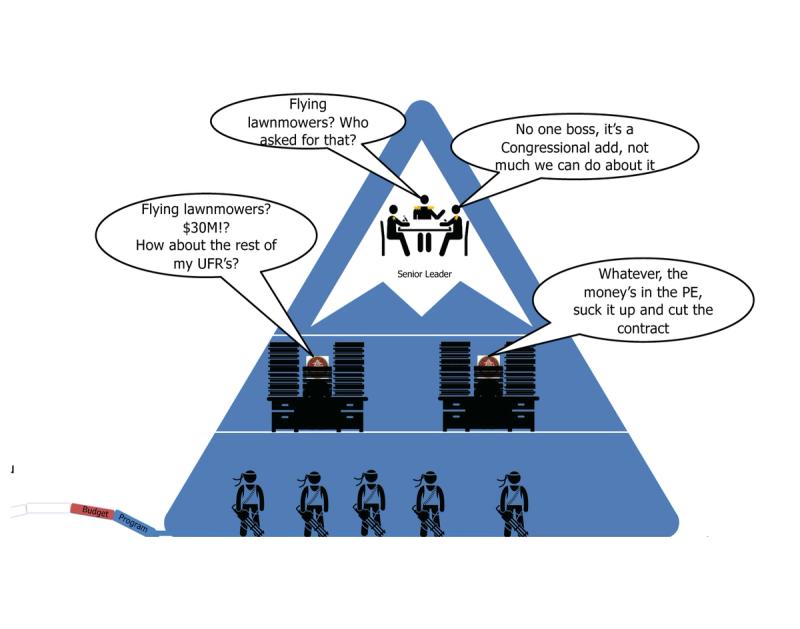

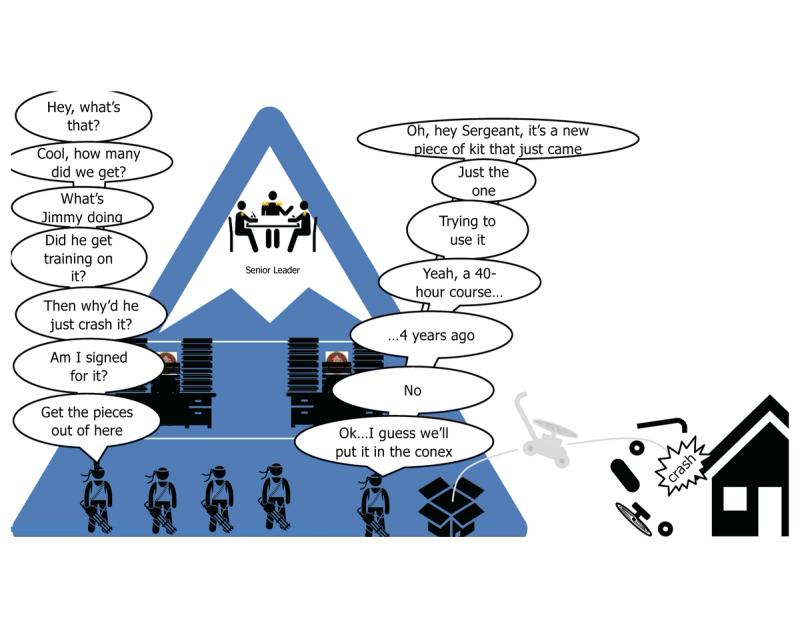

So here's what typically happens:

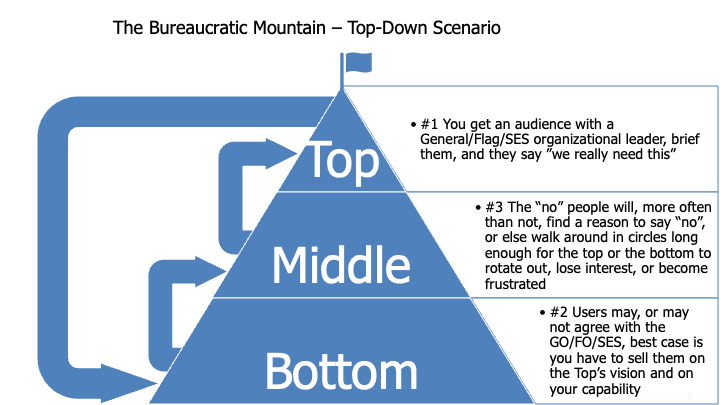

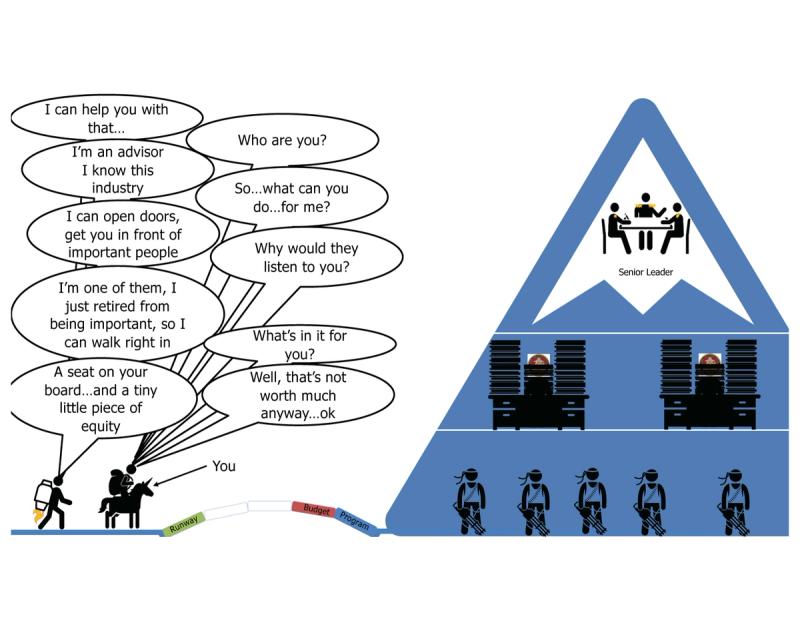

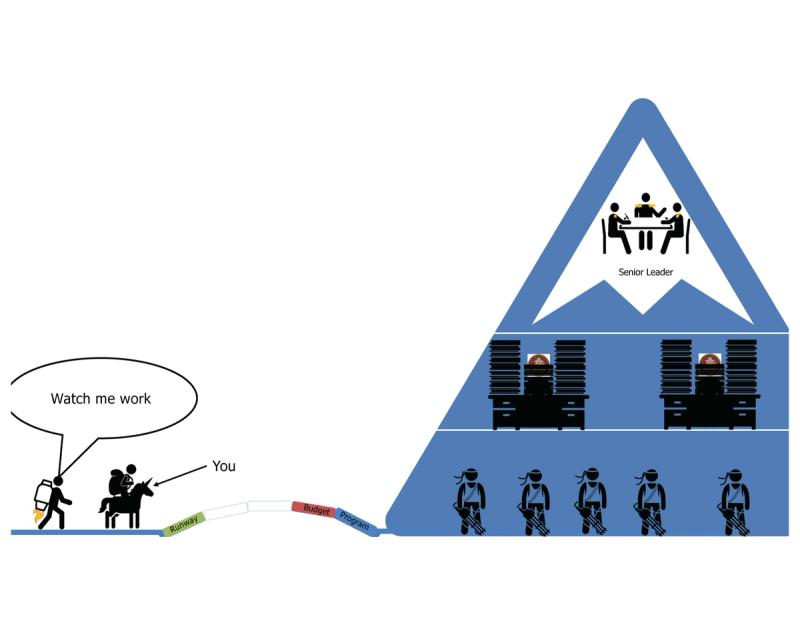

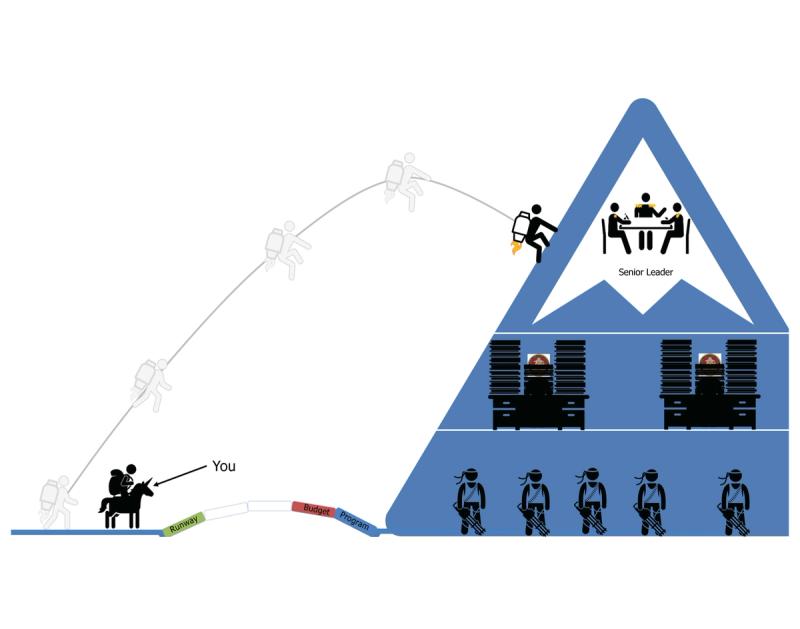

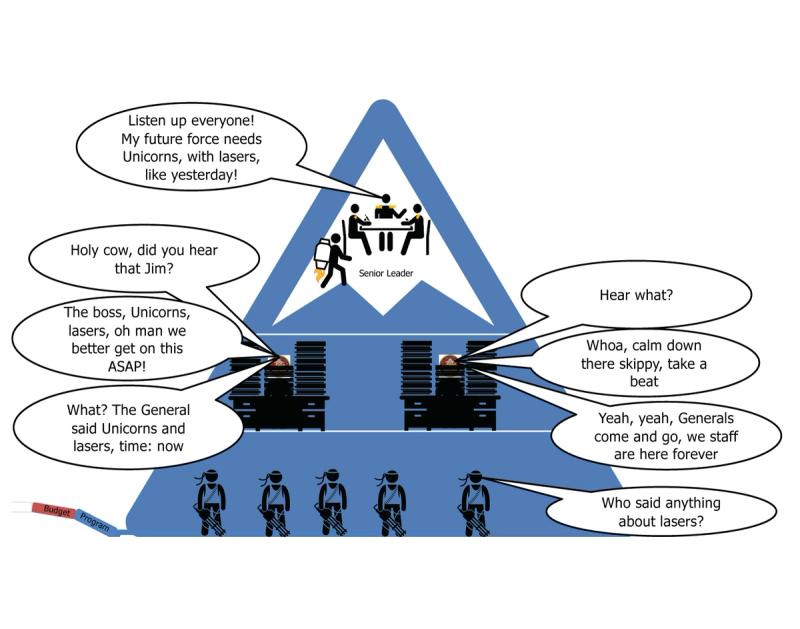

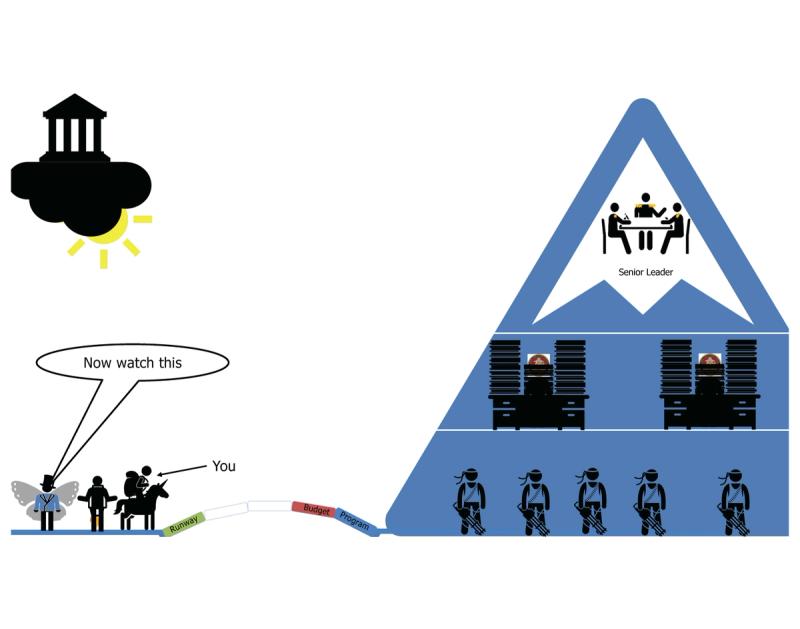

There are variations of this model, there's the top-down approach, for those lucky enough to talk to a General Officer/Flag Officer (GO/FO):

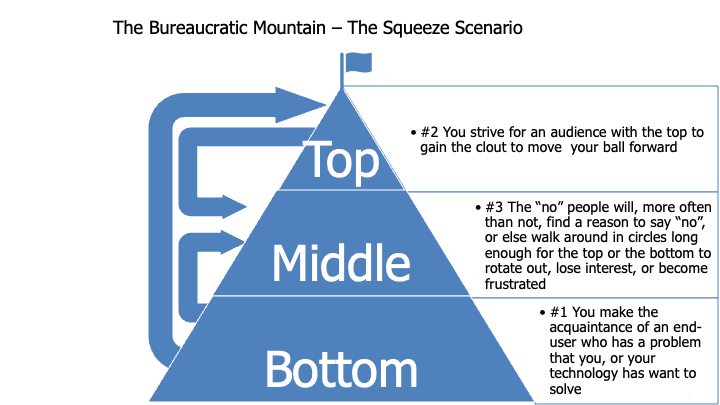

There's also the middle squeeze, for those who have a connection to the top and the bottom:

The least common (because it's hardest and slowest) is the mountain climb:

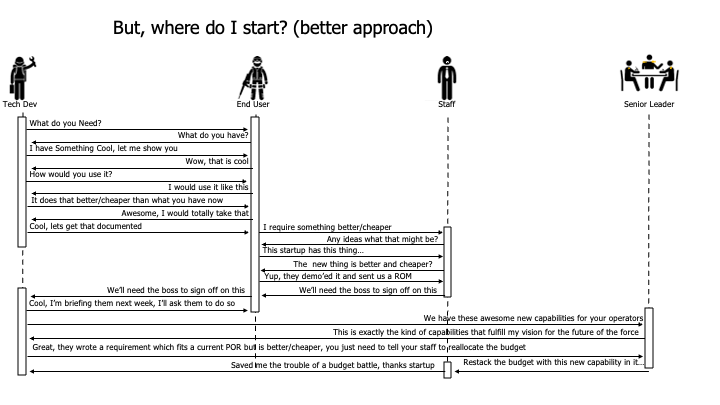

But here's the thing, there's no shortcut to a real win, this is how you want things to go if you want to end up in a PoR:

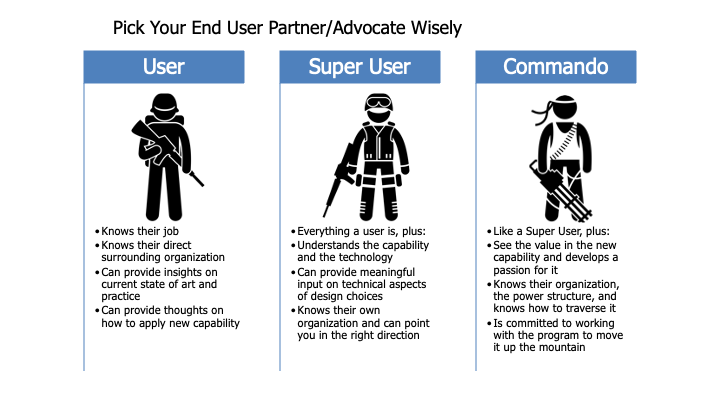

Keep in mind, you'll likely need and end-user both to inform your product development and to advocate for your capability. But not all end-users are created equal. Ideally you want one who knows their job (can inform your development), who is passionate about new capabilities (is willing to spend their free time advocating for your capability), AND knows their organization (knows who to advocate with). These end users are admittedly few and far between.

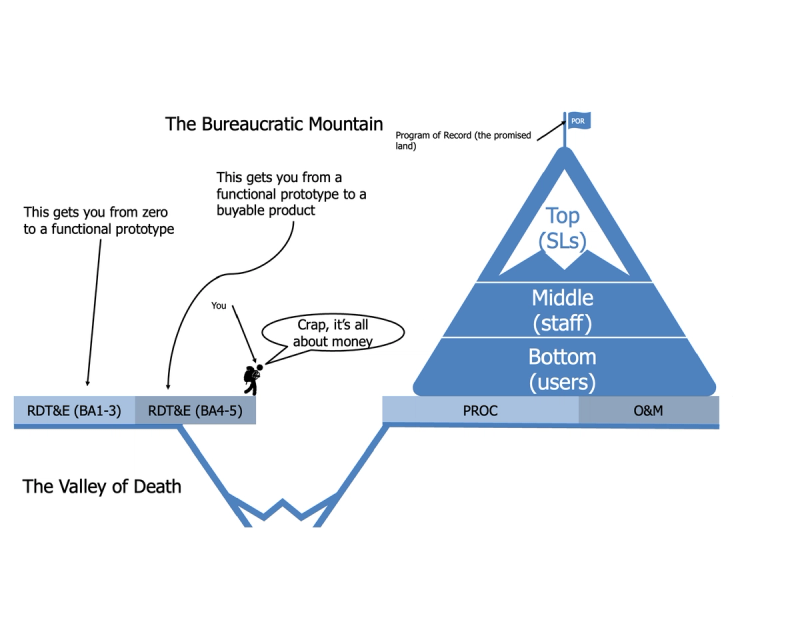

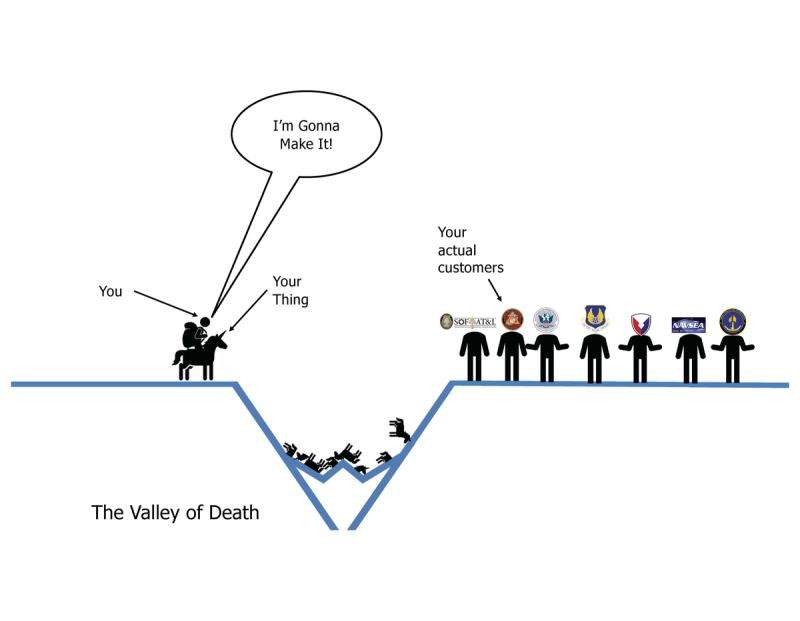

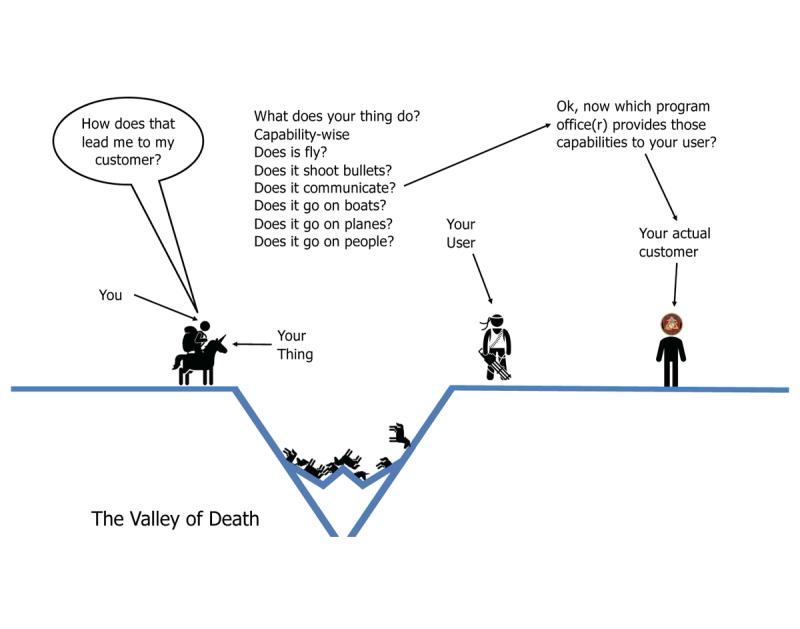

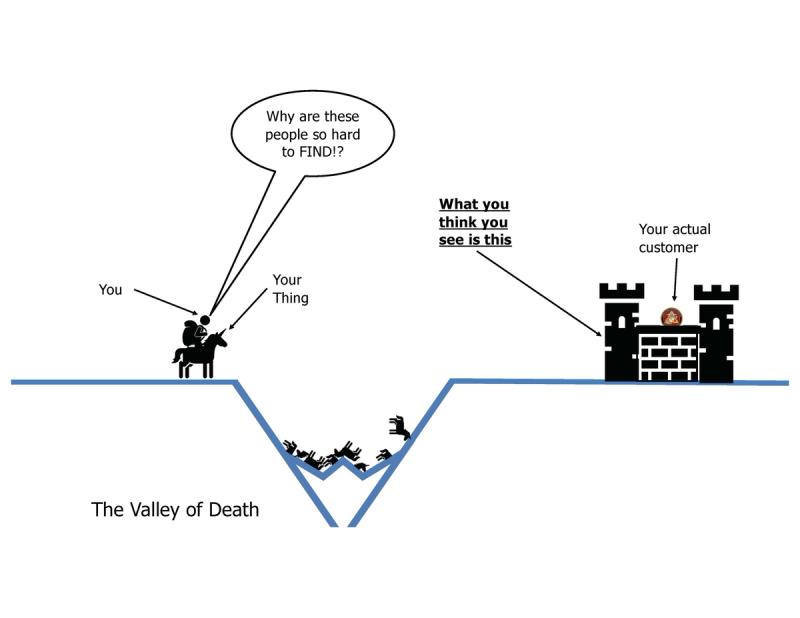

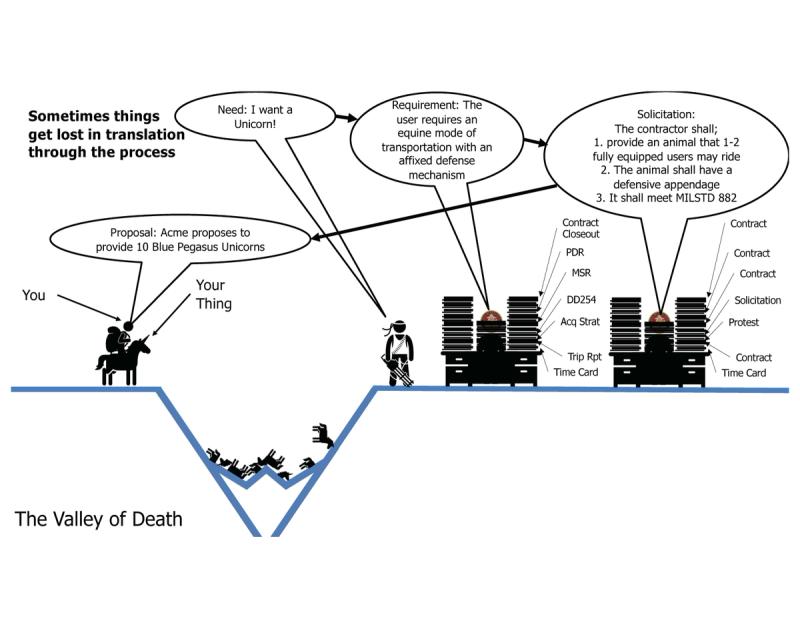

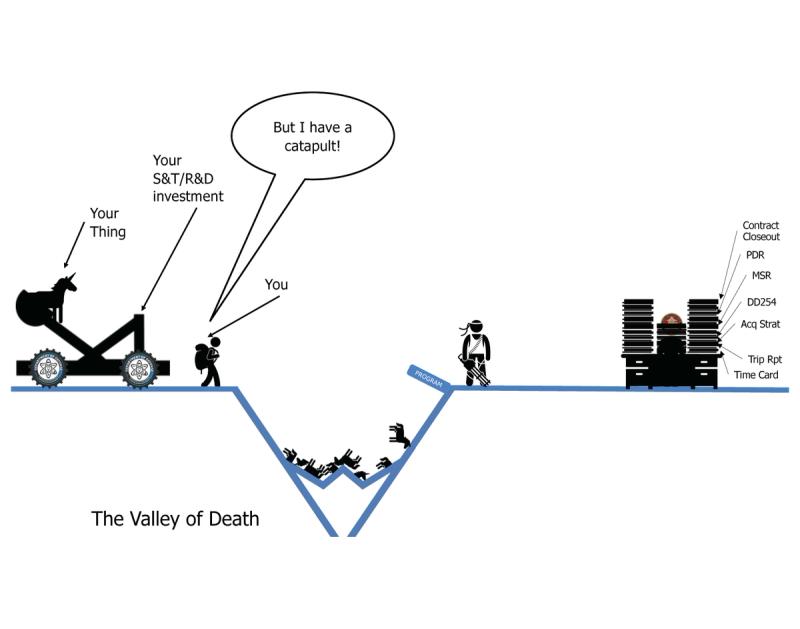

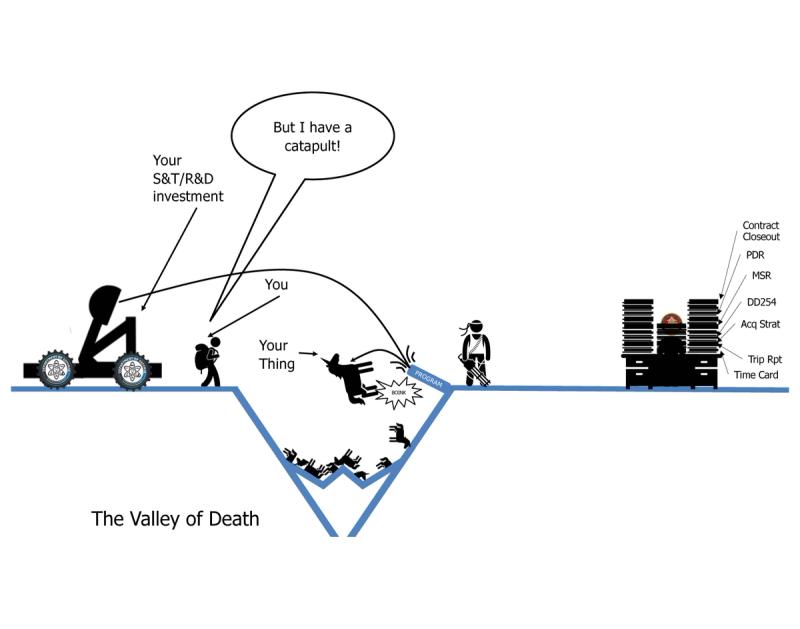

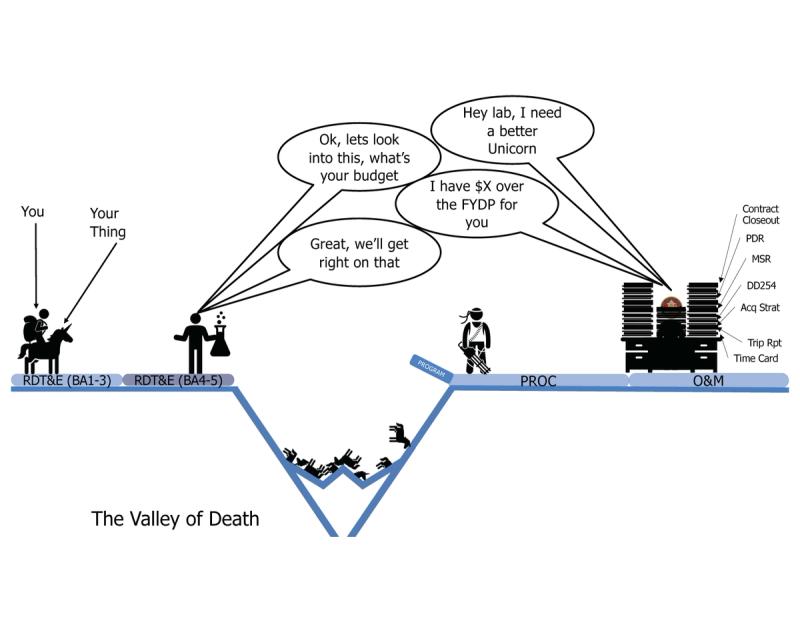

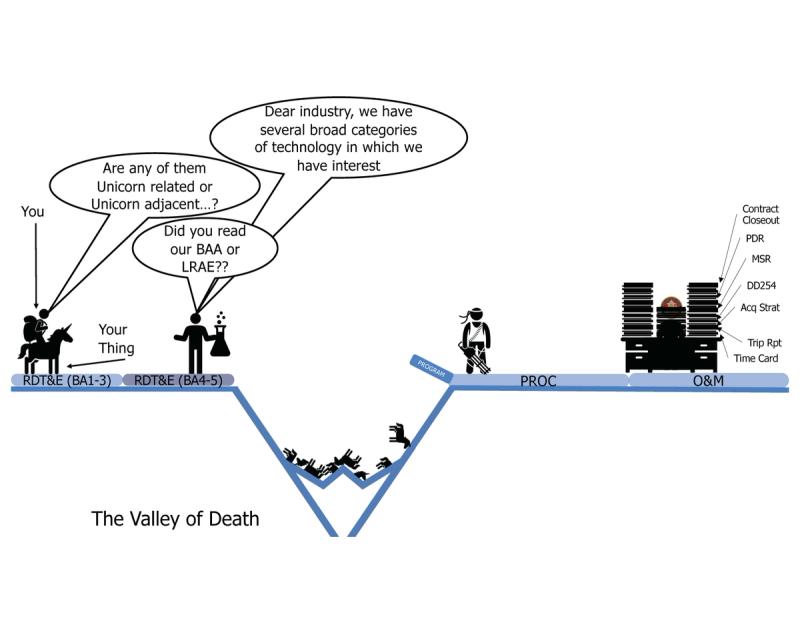

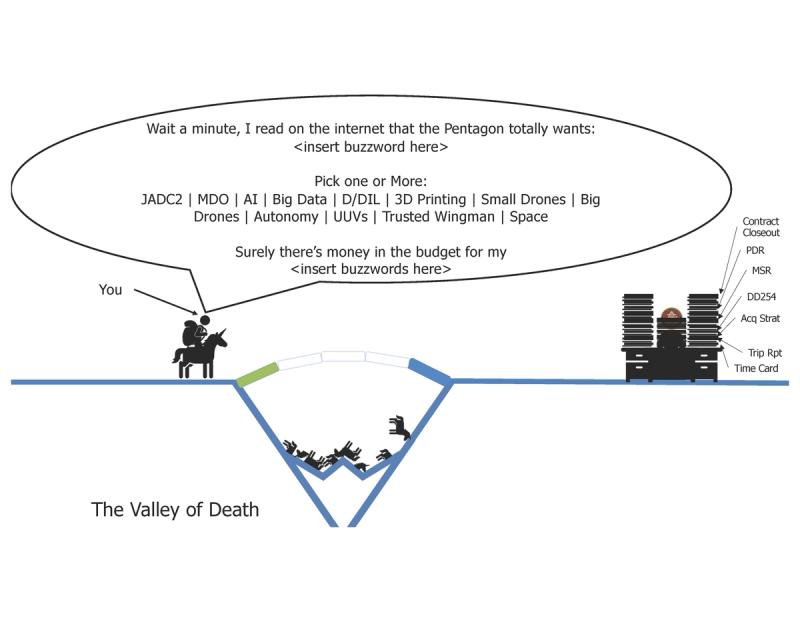

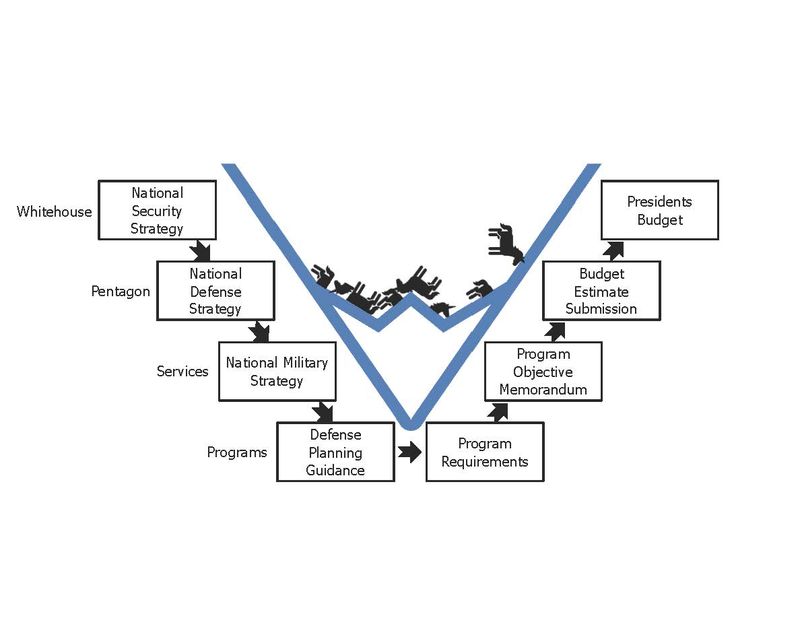

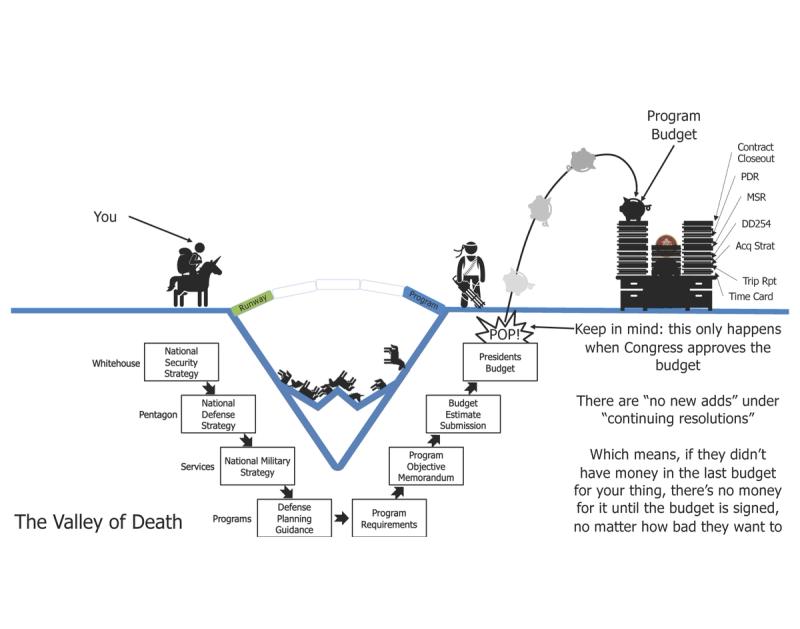

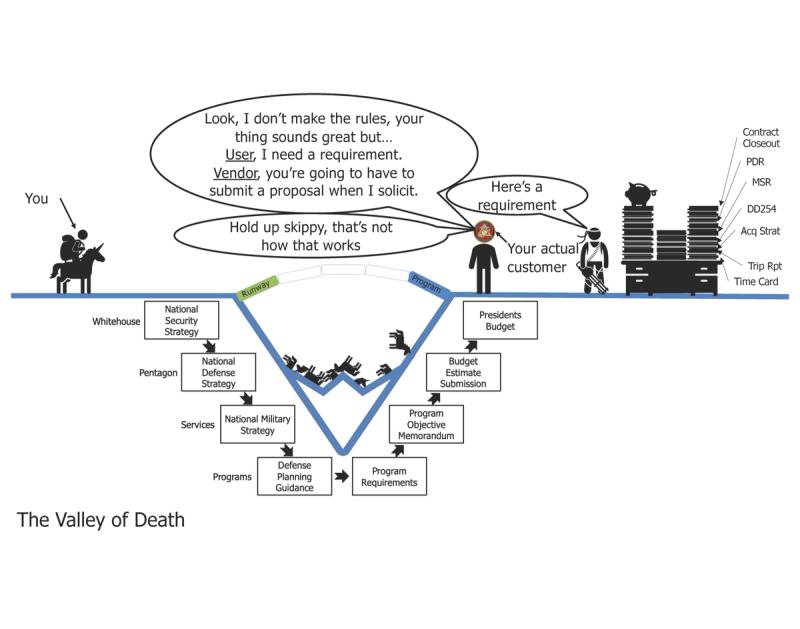

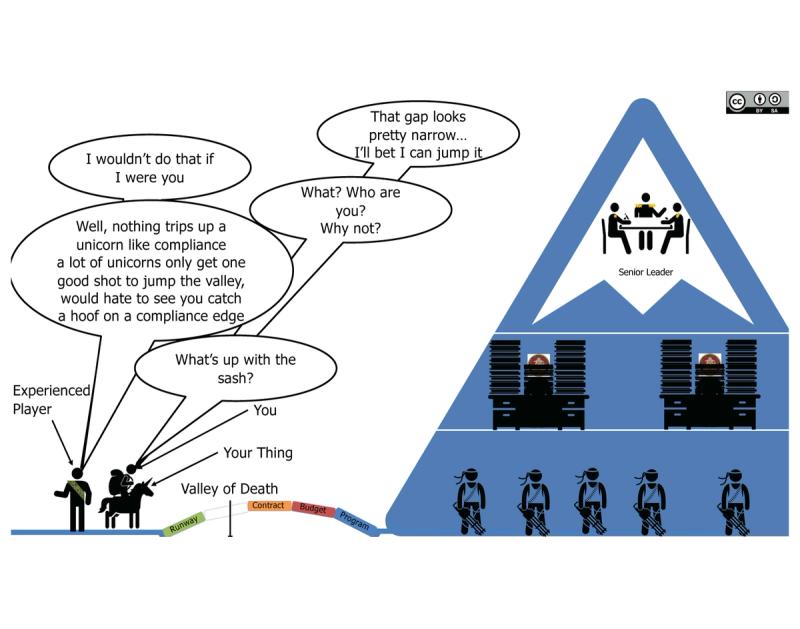

What About the Valley of Death?

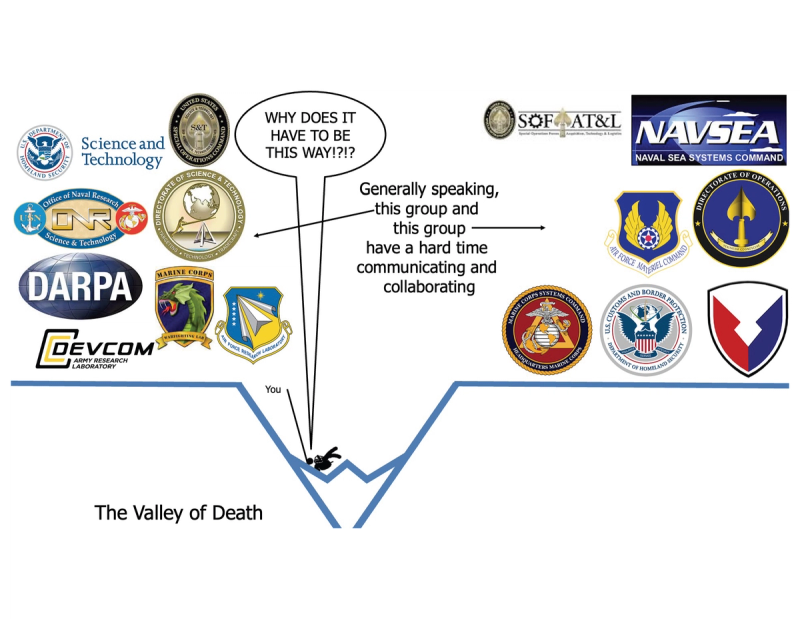

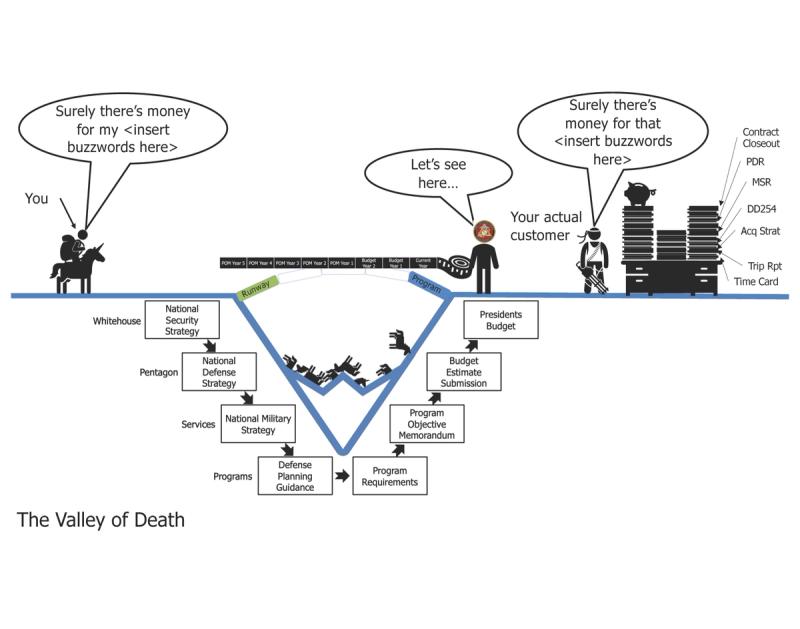

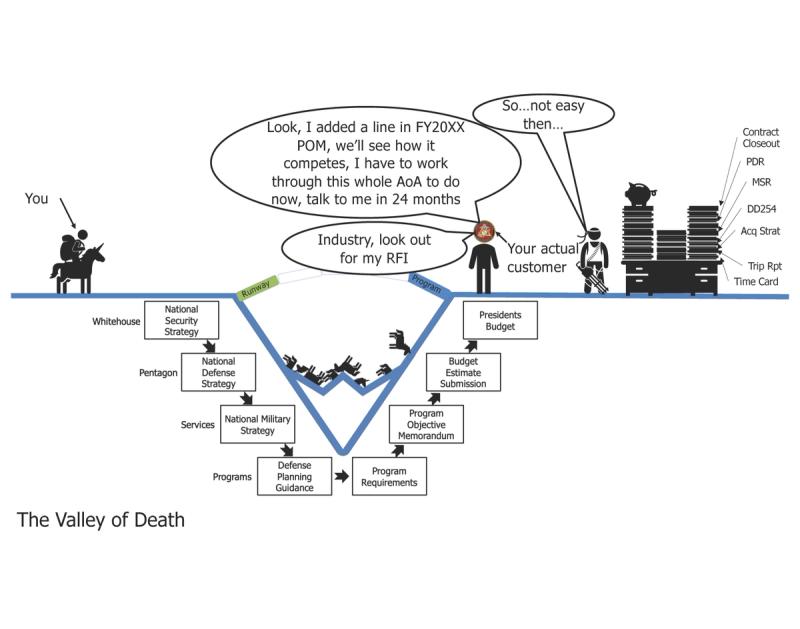

The valley of death is the chasm of technology transition from S&T/R&D organizations and the acquisition organizations they are built to serve.

Why does the valley of death exist? That's a big question with many answers, the central answer is the process.

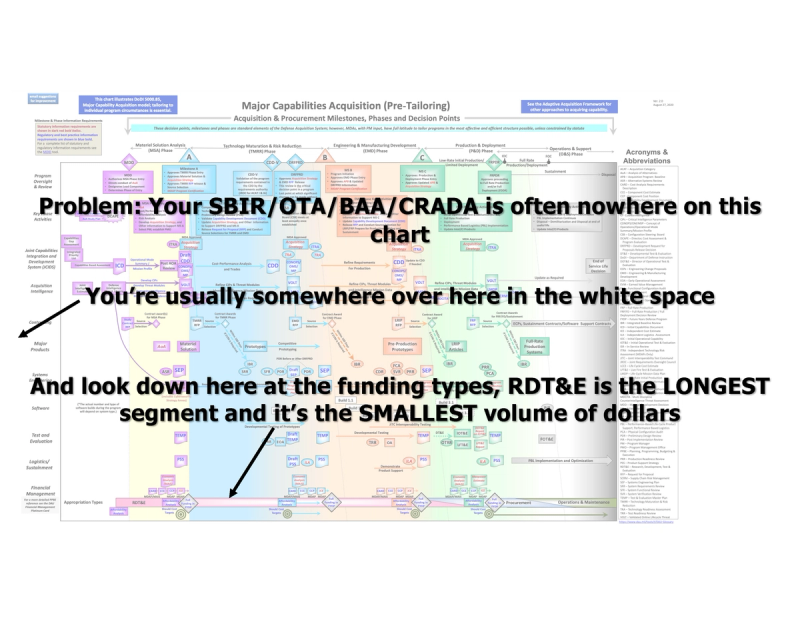

If you haven't looked at "The Chart" you may not be familiar with the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS), that's ok, it'll take you hours and hours to wrap your head around it.

The bottom line goes like this:

Every 4 years there's a national security strategy.

From that comes the national defense strategy

From that comes an assessment of how well the DoD will meet the specified strategy.

From that the military Services determine what they need to build and buy.

From that, the RDT&E shops are supposed to do research to deliver the future capabilities needed.

From those, the acquisition program managers are supposed to pluck the tech they need to achieve the strategy.

Problem is, that takes forever, and everyone is impatient to be more technologically advanced NOW.

So there's a ton of bootstrapped R&D programs out there investing in emergent tech.

Sure, there's the Adaptive Acquisition Framework where you can shortcut the long process, let me know if that works for you. Chances are, if you're reading this, you've experienced the reality of things taking really long because of the legacy process that everyone is trying to bootstrap around.

Mind you, there are plenty of R&D shops that make a decent living by winning DARPA contracts and building tech they have no intention to productize.

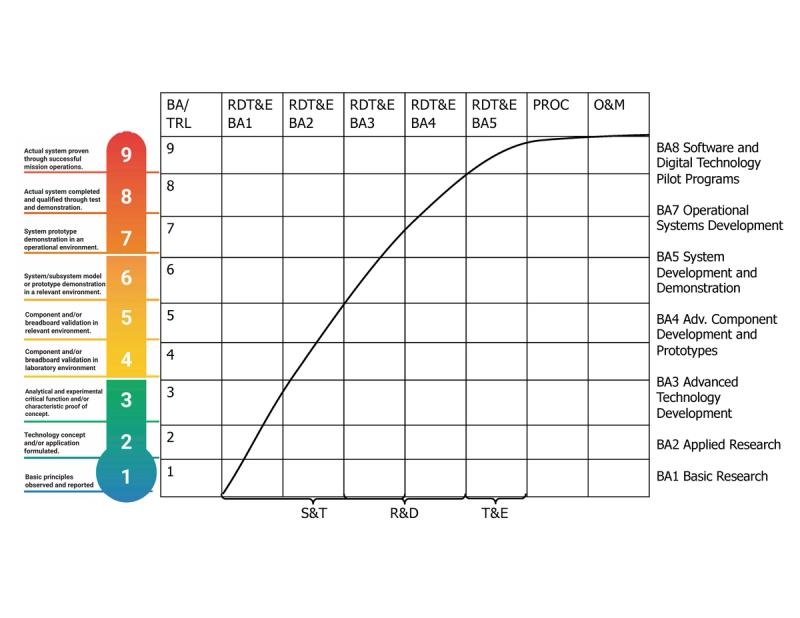

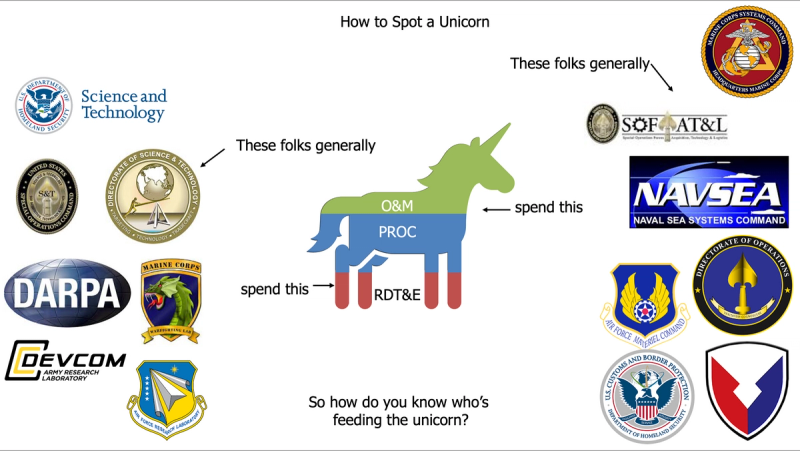

However, if you're a startup, you and your investors are looking for a big exit, so you want to get the big dollars from Procurement (PROC) and Operations and Maintenance (O&M), and those come from a program of record.

So, again, why is there a valley of death???

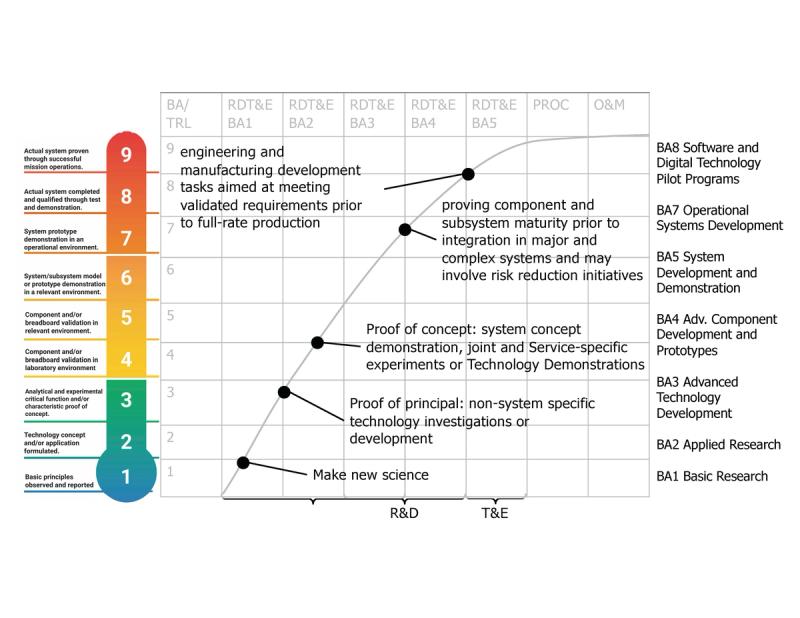

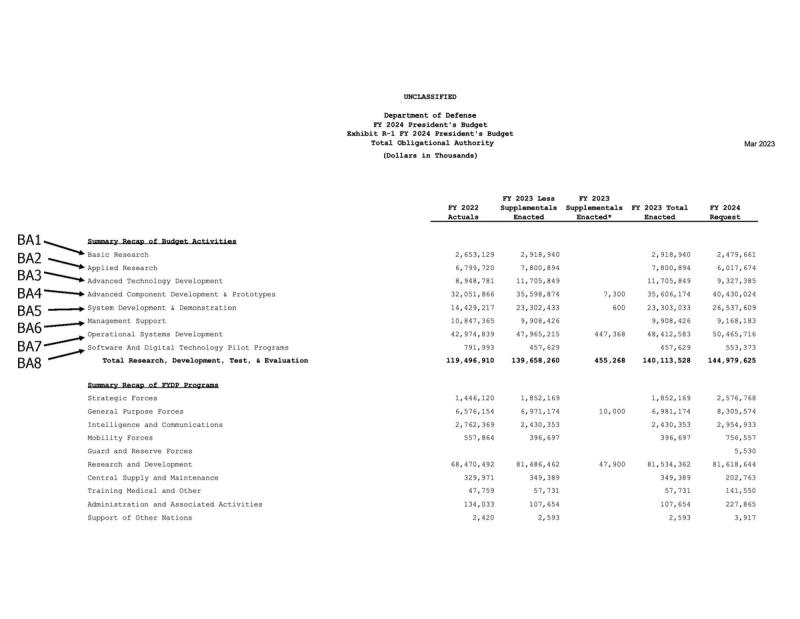

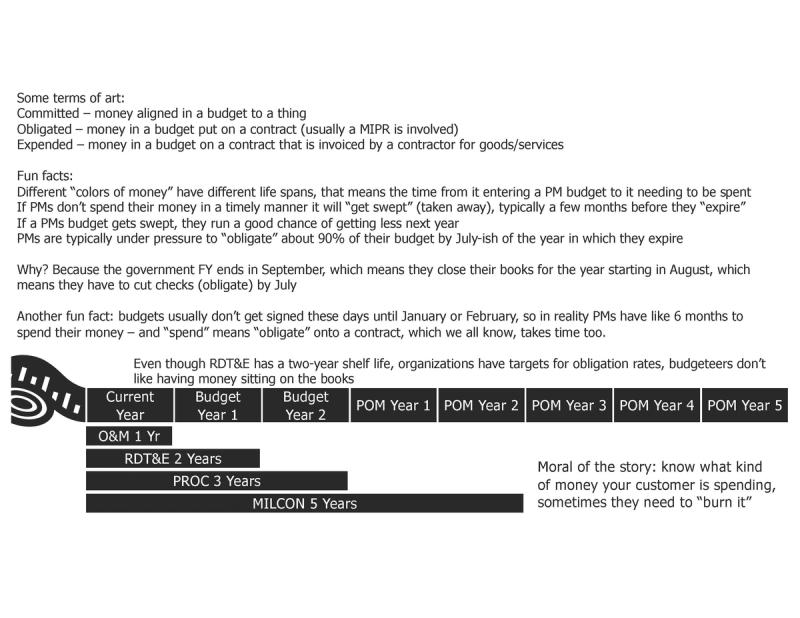

Money is AN ANSWER. There are different "colors of money", the one that funds all the development and experimentation is RDT&E.

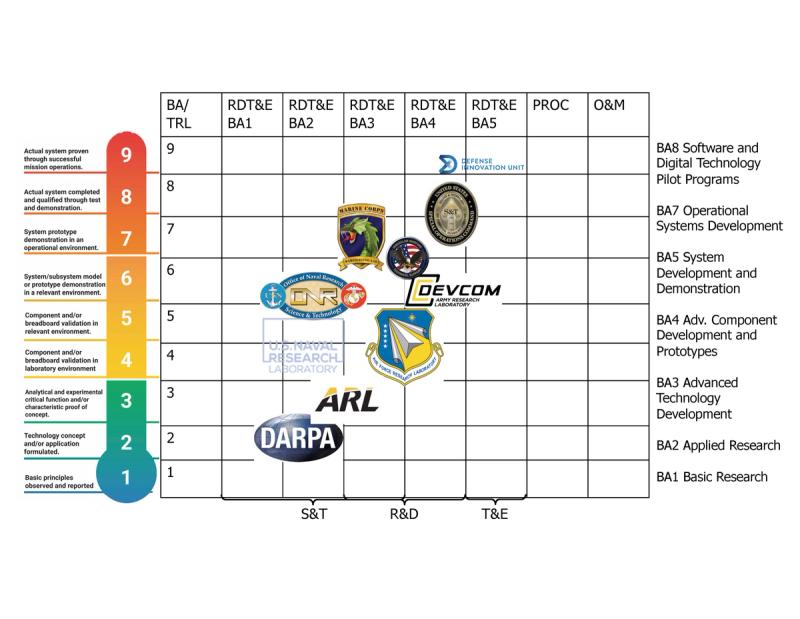

And there are different "Budget Activities", some fund for fundamental research, others fund prototype maturation. Different organizations have different pots of RDT&E, for instance, DARPA doesn't have BA 4 and 5, SOCOM S&T does, so not all S&T orgs are the same.

In general though, the folks who spend RDT&E are different from hose who spend PROC and O&M.

The real challenge is that these folks don't communicate or collaborate very well. Bottom line.

It's not their fault necessarily, they each have jobs to do and they are very different.

R&D Program Managers need to be out there doing cutting edge science stuff, finding the next big thing, managing and buying down technical risk, proving the realm of the possible.

Acquisition Program Mangers need to be out there fielding capabilities, making sure they get the right number of units out of a producer, make sure they get delivered to the right place at the right time.

R&D Program Managers only really need to talk to Acquisition Program Managers when they have a new things that's actually going to work, which is not all the time.

Acquisition Program Managers really only need to talk to R&D Program Managers when the things they're fielding are no longer sufficient for the force, which is not all the time.

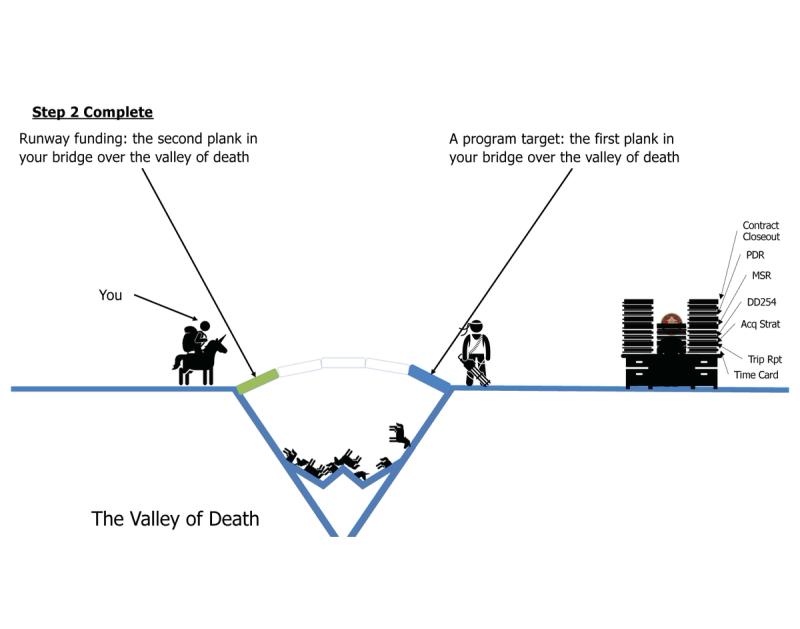

So what do you do about it? You gotta build the bridge, like it or not that's how you win. Let's talk about that.

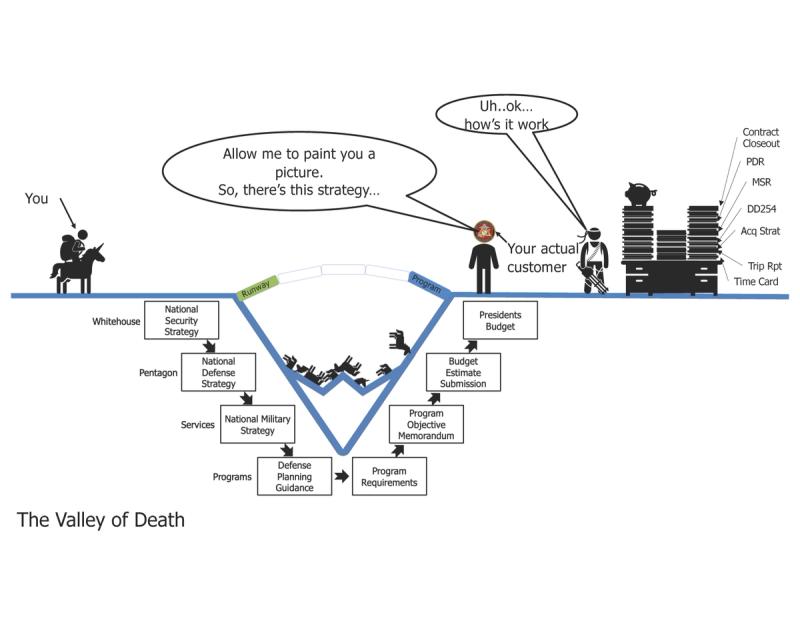

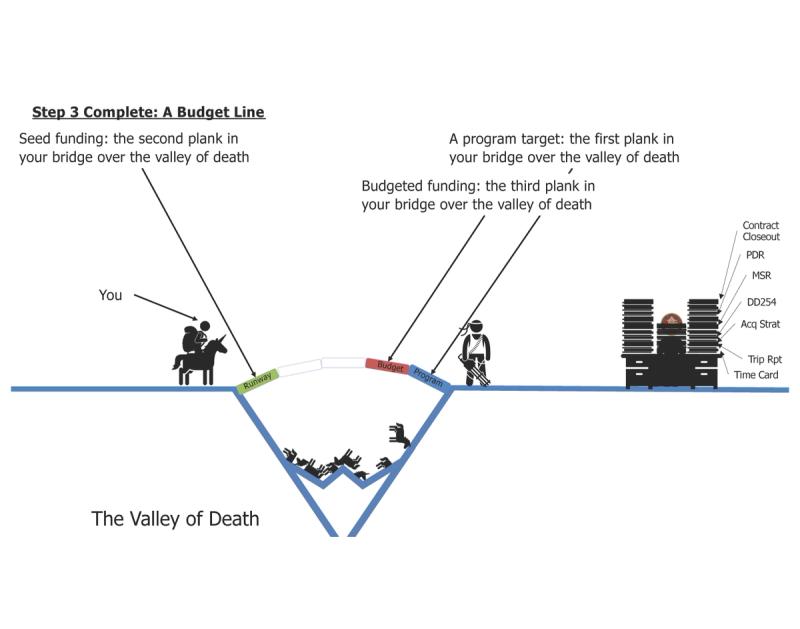

Bridging the Valley of Death

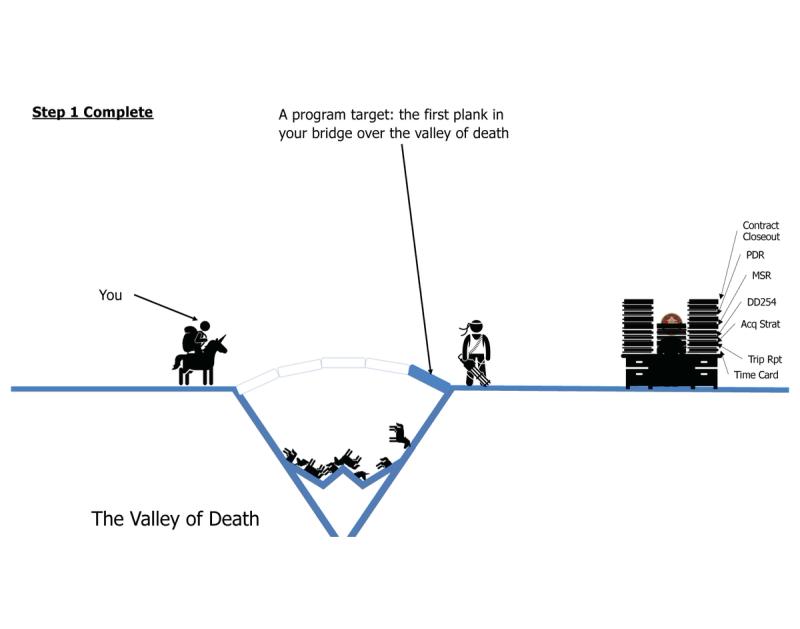

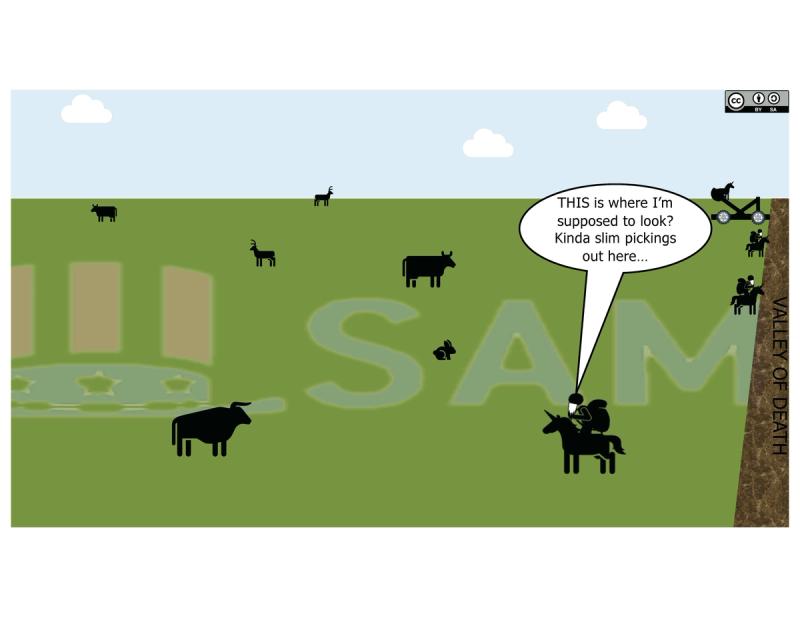

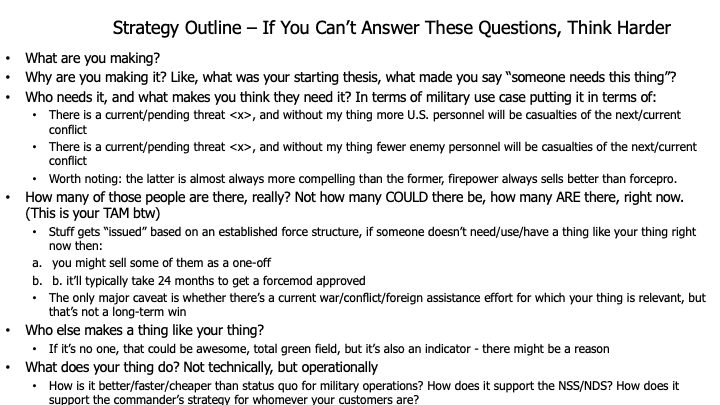

Step 1: Spot Your Landing

The valley of death is wide and full of unicorns like yours, but it’s wider in some spots than others, and it’s infinitely wide if you’re not looking for the other side of the chasm. To put it plainly, if you’re not sure what you’re really selling, who wants it or needs it, or worse you try selling to the wrong person, then you’re going to fail.

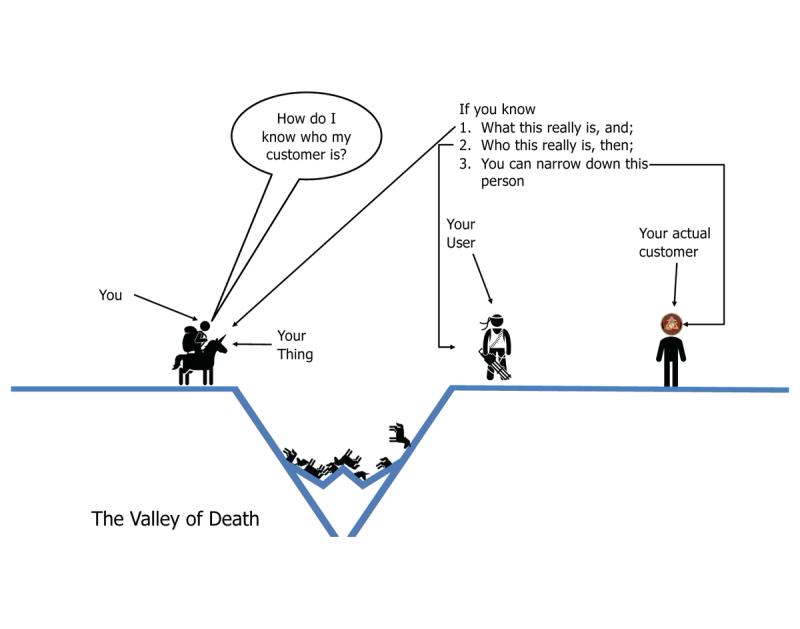

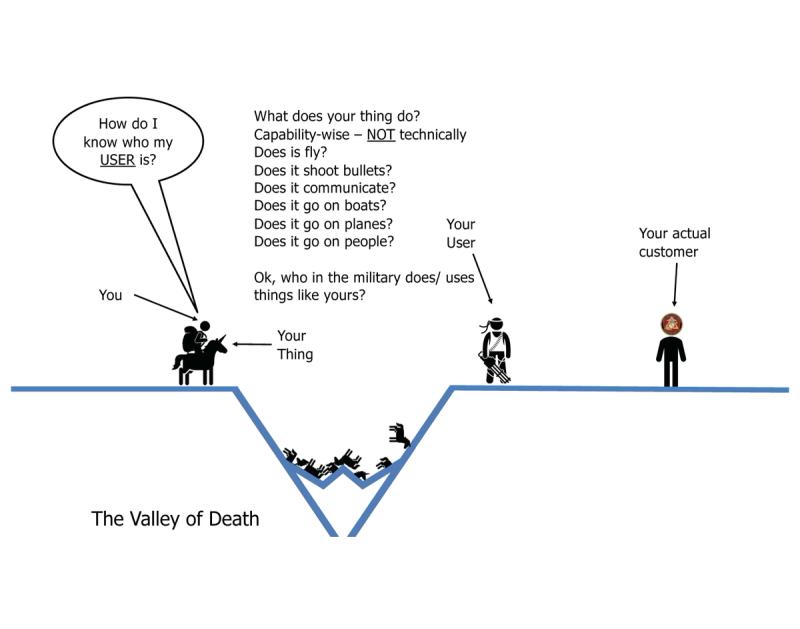

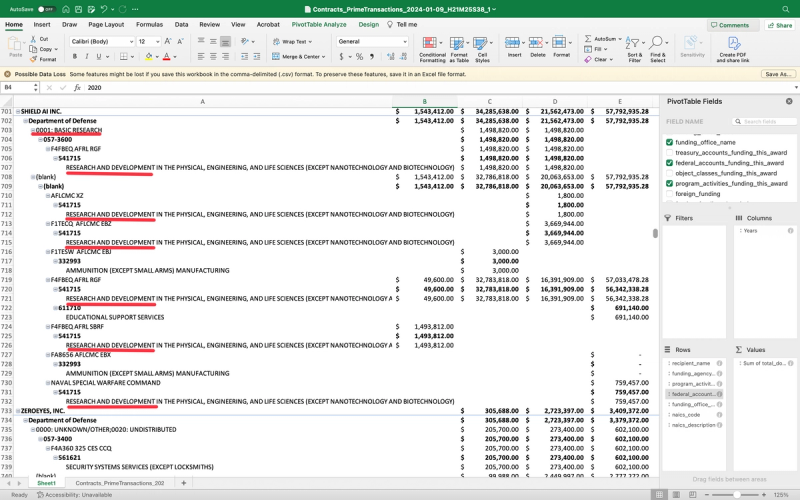

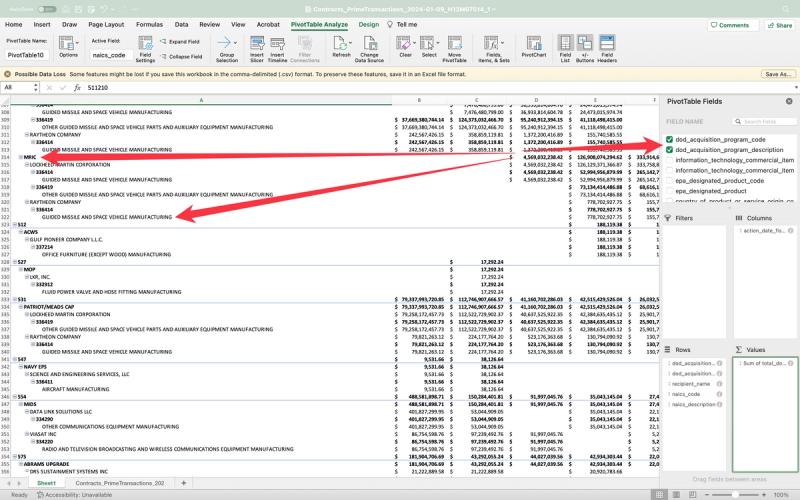

So let’s start with the super simple business question, what are you making?

To be clear, you need to answer this question two ways:

- That is the category of the thing (communications, lethality, mobility, jammers, jets, rocket ships, whatever).

- The capability of your thing (what value does it add to the user).

Why do we differentiate this?

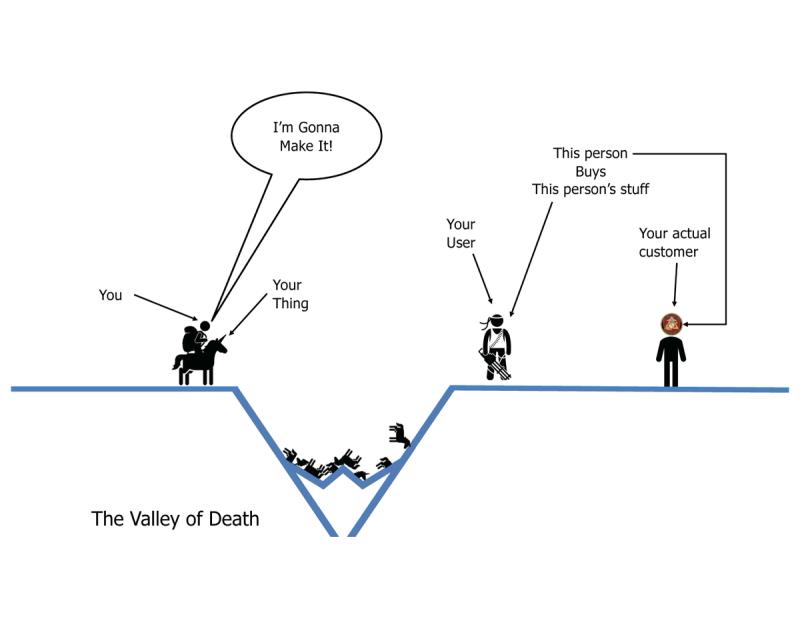

Well, #1 is for the PM’s (your actual customers), and number #2 is for the users.

While you're at it, you might ask yourself why are you making it? Like, what was your starting thesis, what made you say “someone needs this thing”? To me this sounds like a silly question, but objectively I know there’s a lot of solutions out there looking for problems.

Bottom line, end-users don't buy things, acquisition program managers do. So you can talk to users until you're blue in the face, but if you don't get in contact with a PM, you're probably going to have a bad time.

BUT! you do need to START with the end users, because that plus what you're building will determine which PM to contact.

So lets talk about end users...

Who (do you think) needs what you're making, and what makes you think they need it? In terms of military use case putting it in terms of:

There is a current/pending threat <x>, and without my thing more U.S. personnel will be casualties of the next/current conflict

There is a current/pending threat <x>, and without my thing fewer enemy personnel will be casualties of the next/current conflict

Worth noting: the latter is almost always more compelling than the former, firepower always sells better than forcepro, and training sells worst of all. Ironically there’s often a pile of training money left over at the end of the fiscal year but it seldom goes towards technology investment, it’s a whole color of money thing, just take my word for it.

How many of those people are there, really? Not how many COULD there be, how many ARE there, right now. (This is your TAM btw)

Stuff gets “issued” based on an established force structure, if someone doesn’t need/use/have a thing like your thing right now then:

you might sell some of them as a one-off

b. it’ll typically take 24 months to get a forcemod approved

The only major caveat is whether there’s a current war/conflict/foreign assistance effort for which your thing is relevant, but that’s not a long-term win

Who else makes a thing like your thing?

If it’s no one, that could be awesome, total green field, but it’s also an indicator - there might be a reason

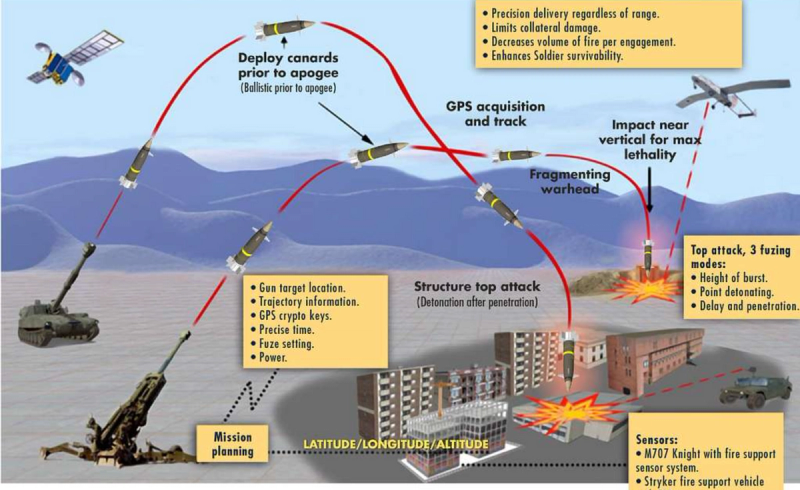

What does your thing do? Not technically, but operationally

How is it better/faster/cheaper than status quo for military operations? How does it support the NSS/NDS? How does it support the commander’s strategy for whomever your customers are?

Word to the wise: don’t build tech for the last war.

Seriously, avoid the following tech if you can help it: counter-IED, anything to do with door kicking and direct action, stuff that’s hyper niche to Special Operations, fixed-wing ISR. Just a suggestion. If you don’t know what problems you should tackle, look up some strategy documents like “Army 2035”.

Why all this focus? Because what you’re building and for whom you’re building it determines who foots the bill, bottom line. If you cant answer the above question then you cant figure out the answer to this golden question.

Who are these mythical PMs, its pretty simple actually.

Army

JOINT PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE ARMAMENTS & AMMUNITION

JPEO Armaments & Ammunition leads the development, procurement, and delivery of lethal armaments and ammunition providing joint warfighters with overmatch capabilities to defeat current and future threats. https://jpeoaa.army.mil/jpeoaa/

JOINT PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE CHEMICAL, BIOLOGICAL, RADIOLOGICAL AND NUCLEAR DEFENSE

JPEO-CBRND is the Joint Service’s lead for the development, acquisition, fielding, and life cycle support of CBRN defense equipment and medical countermeasures. https://www.jpeocbrnd.osd.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE ASSEMBLED CHEMICAL WEAPONS ALTERNATIVES

PEO ACWA is responsible for the safe destruction of the remaining U.S. chemical weapons stockpile in Colorado and Kentucky. https://www.peoacwa.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE AVIATION

PEO Aviation supports Army commanders by delivering capabilities to the Combat Aviation Brigade. The organization supports Army Readiness by leading and executing life cycle management for all Army aviation weapons systems. https://www.army.mil/PEOAviation

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE COMBAT SUPPORT AND COMBAT SERVICE SUPPORT

PEO CS&CSS is responsible for the life cycle of approximately 20% of the Army’s total equipment programs spanning the Engineer, Ordnance, Quartermaster, and Transportation portfolios. https://www.peocscss.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE COMMAND, CONTROL, COMMUNICATIONS-TACTICAL

PEO C3T is supporting the Army’s new network modernization by delivering a tactical network designed to integrate unified network transport, deliver a common operating environment, enable Joint and coalition interoperability, and develop more mobile and expeditionary command posts. https://peoc3t.army.mil/c3t/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE ENTERPRISE INFORMATION SYSTEMS

PEO EIS provides and manages the information technology network and day-to-day business systems that directly support every domain, branch, unit, and Soldier in the Army. https://www.eis.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE GROUND COMBAT SYSTEMS

PEO GCS is responsible for providing world-class affordable, relevant, and sustainable ground combat equipment to Soldiers. https://www.peogcs.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE INTELLIGENCE ELECTRONIC WARFARE & SENSORS

PEO IEW&S delivers capability to Soldiers now through affordable and adaptable programs that pace the threat. https://peoiews.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE MISSILES AND SPACE

PEO MS delivers integrated offensive and defensive fires materiel solutions to defeat the threats of today and tomorrow. https://www.msl.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE SIMULATION, TRAINING AND INSTRUMENTATION

PEO STRI develops, acquires, provides, and sustains simulation, training, testing, and modeling solutions to optimize warfighter readiness. https://www.peostri.army.mil/

PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE SOLDIER

PEO Soldier rapidly delivers agile and adaptive, leading-edge Soldier capabilities to provide combat overmatch today and be more lethal tomorrow. https://www.peosoldier.army.mil/

Navy

PEO Aircraft Carriers focuses on the design, construction and delivery, and life-cycle support of all aircraft carriers and the integration of systems into aircraft carriers.

PEO Integrated Warfare Systems develops, delivers and sustains operationally dominant combat systems for Sailors.

PEO Ships manages acquisition and complete life-cycle support for all U.S. Navy non-nuclear surface ships. These ships range from frontline combatants to amphibious ships that transport Marines and their equipment to supply and replenishment cargo ships. For these and all other non-nuclear surface craft, PEO Ships maintains “cradle to grave” responsibility including research, development, acquisition, systems integration, construction and lifetime support.

PEO Attack Submarines aligns Virginia-class efforts under one Flag officer.

PEO Strategic Submarines (formerly PEO Columbia) proactively manages the Ohio-to-Columbia transition, including strategic shore infrastructure and industrial base capacity, to ensure uninterrupted sea-based strategic deterrent coverage into the 2080s.

PEO Undersea Warfare Systems enables the delivery of enhanced combat capability, with improved cybersecurity and resiliency, to all submarine platforms.

PEO Unmanned and Small Combatants designs, develops, builds, maintains and modernizes the Navy's expanding family of unmanned maritime systems, mine warfare systems, and Small Surface Combatants by employing the full arsenal of acquisition authority to develop and deliver innovative solutions and technologies to support the Navy.

Now the Marine Corps is part of the Department of the Navy, so there's some shared PEOs for things like IT

Program Executive Officer Land Systems (PEO LS):

It's the only Program Executive Office in the Marine Corps. It focuses on developing, delivering, and sustaining lethal capabilities worth over $8 billion across five program offices.

Subordinate Program Offices:

Advanced Amphibious Assault (PM AAA): Manages Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV) and Assault Amphibious Vehicle (AAV).

Air Command Control and Sensor Netting (PM AC2SN): Oversees systems like Common Aviation Command and Control System (CAC2S) and Composite Tracking Network (CTN).

Ground/Air Task Oriented Radar (PM G/ATOR): Handles G/ATOR system.

Ground-Based Air Defense (PM GBAD): Manages systems like Light Marine Air Defense Integrated System (L-MADIS) and Marine Air Defense Integrated System (MADIS).

Light Armored Vehicles (PM LAV): Focuses on Light Armored Vehicle (LAV) and Advanced Reconnaissance Vehicle (ARV)

Marine Corps Systems Command (MCSC):

Subordinate Program Offices and Systems:

Command & Control Systems: Delivers interoperable C2 systems to the Fleet Marine Forces.

Communications Systems: Focuses on communication technologies for the Marine Corps.

Intelligence Systems: Dedicated to intelligence-related systems.

Infantry Weapons: Manages the development and deployment of infantry weapons.

Fire Support Systems: Oversees the fire support capabilities.

Long Range Fires: Focuses on long-range fire support technologies.

Engineer Systems: Handles engineering-related systems and technologies.

Light Tactical Vehicles: Manages light tactical vehicle programs.

Medium/Heavy Tactical Vehicles: Focuses on medium and heavy tactical vehicles.

Supply and Maintenance Systems: Responsible for supply and maintenance related systems.

Air Force

Air Force Lifecycle Managment Center

Air Force Security Assistance & Cooperation Directorate (AFSAC) - (WF): This directorate is responsible for managing the Air Force's Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. It facilitates the sale of defense articles, services, and training to foreign partners and allies to bolster security cooperation and policy objectives.

Agile Combat Support Directorate (ACS) - (WN): ACS provides life cycle management for agile combat support systems and services, including logistics, sustainment, and deployment capabilities for Air Force operations.

Armament Directorate (EB): This directorate oversees the development, acquisition, testing, deployment, and sustainment of air-delivered weapons. It focuses on ensuring that combat forces are equipped with reliable and effective munitions.

Bombers Directorate (WB): The Bombers Directorate manages the Air Force's fleet of bomber aircraft. It ensures these strategic assets are supported throughout their life cycle with modernization, maintenance, and upgrades to sustain their long-range strike capabilities.

Business and Enterprise Systems Directorate (BES) - (GB): BES is tasked with providing and maintaining IT systems and solutions that support the management of the Air Force's resources, including finances, supply chains, and human resources.

Command, Control, Communications, Intelligence & Networks Directorate (C3I&N) - (HN): This directorate focuses on acquiring and sustaining C3I and network systems that support global Air Force operations, ensuring effective communication and information dominance.

Digital Directorate (HB): Formerly known as the Battle Management Directorate, this unit is responsible for digital transformation and modernizing software development and acquisition processes across the Air Force.

Fighters and Advanced Aircraft Directorate (WA): This office manages the life cycle of the Air Force's fighter aircraft portfolio. It includes the development, acquisition, and sustainment of current and future tactical fighter and advanced aircraft systems.

Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Special Operations Forces Directorate (ISR/SOF) - (WI): The ISR/SOF Directorate provides acquisition support for the Air Force's ISR and SOF platforms, including drones, reconnaissance aircraft, and related systems.

Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) - (WJ): This directorate represents the Air Force's interests in the multi-service F-35 Lightning II program. It manages integration, production, and sustainment efforts for the F-35 within the Air Force.

Mobility & Training Aircraft Directorate (WL): Responsible for the acquisition and support of air mobility and training aircraft, this directorate ensures that platforms like transport planes and trainers meet Air Force needs.

Presidential and Executive Airlift Directorate (WV): This directorate provides acquisition and sustainment for aircraft used in the Presidential Airlift Group and other executive transport, ensuring that these high-priority assets are mission-capable.

Propulsion Directorate (LP): The Propulsion Directorate focuses on the acquisition, development, and sustainment of propulsion systems, including engines for various Air Force aircraft.

Rapid Sustainment Office (RSO) - (RO): RSO aims to increase the readiness of Air Force aircraft by rapidly fielding sustainment innovations and harnessing new technologies for maintenance and logistics.

SOCOM

PEO Fixed Wing (FW): Manages the acquisition and development of fixed-wing aircraft and related systems for special operations.

PEO Maritime: Responsible for maritime platforms, including surface and sub-surface vessels tailored for special operations.

PEO Rotary Wing (RW): Oversees rotary-wing aircraft (helicopters) programs, including development and modifications specific to special operations needs.

PEO SOF Warrior: Concentrates on the equipment and combat gear used directly by special operations forces, including tactical equipment and weapons systems.

PEO Special Operations Forces Support Activity: Likely manages the support structure for special operations forces, which may include logistics and sustainment operations.

PEO SOF Digital Applications: Focuses on the development and integration of digital applications, software, and cyber capabilities for special operations forces.

PEO Services: Handles acquisition programs related to services that may encompass training, mission support, and operational services for SOF.

PEO Tactical Information Systems: Manages the acquisition of tactical information systems that provide communication and data exchange capabilities for special operations forces.

Space Force

Space Domain Awareness and Combat Power: SSC provides ground and space-based systems that are essential for the identification, tracking, and deterrence of threats to national security and allied commercial space systems.

Battle Management Command, Control & Communications: SSC integrates technologies and systems to optimize space-based battle management command, control, and communications (BMC3) capabilities across the Department of Defense's (DoD) entire ground, sea, air, and space enterprise.

Space Sensing: SSC is at the forefront of acquisition, development, and sustainment of missile warning, tracking, and defensive (MW/T/MD) systems, space-based environmental monitoring (SBEM), and other strategic and tactical sensing capabilities.

Military Communications & Positioning, Navigation and Timing: This enhances the capabilities and resilience of GPS, SATCOM, and PNT satellites, receivers, and user equipment.

Assured Access to Space: SSC provides launch and on-orbit capabilities used by joint warfighters, combatant commands, intelligence, and civil services, advancing commercial space industry involvement.

Space Systems Integration: This function aligns efforts across partnerships to prevent duplication and ensure interoperability across the spectrum of space systems.

Commercial, Government, and Allied Partnerships: SSC facilitates through supporting offices, which streamline access to commercial services for a greater international partnership on sovereign requirements for space capabilities.

Innovation and Prototyping: SSC engages in robust innovation to ensure the rapid development and capability acquisition is aligned and integrated with combatant command requirements and exercises.

This is far from an exhaustive list, do your own research, it's all available online.

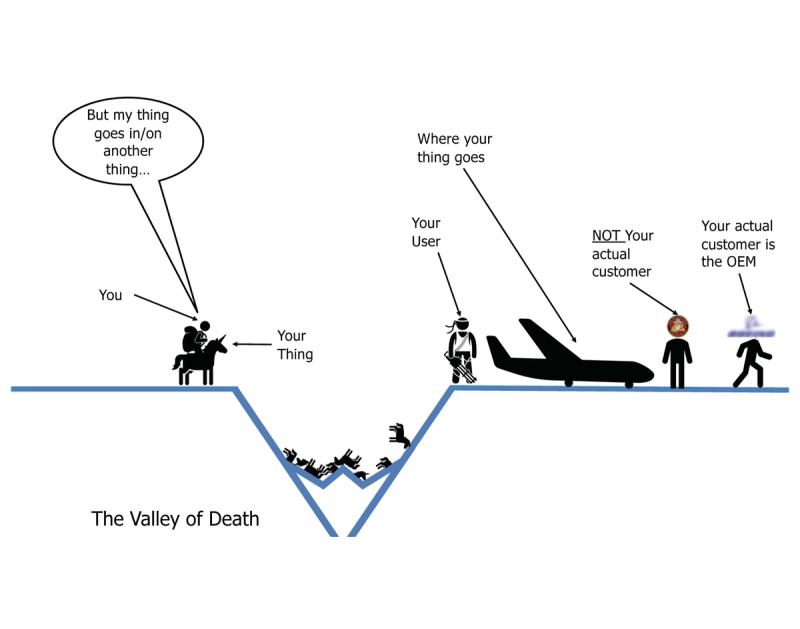

One huge caveat: if you're building a subcomponent or an enhancement to a fielded system that's made by someone else, like say a dongle that plugs into the 1553 bus of an F35, your customer is not the program office.

If your thing is an enhancement to a current system, then your customer is actually the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM). Now, if your thing literally bolts on, as in you bolt a radio into a Humvee or you put a standalone laptop on a bridge, then this typically does not apply. But if you plan to ENHANCE a current capability/system with your thing, so that it does IT'S thing better, then you have to sell to the OEM.

Why? because that how the system works. THAT company is on contact to deliver their thing, according to a spec in a requirement. So you either have to

a. convince the program office to change their requirement and write YOUR thing into the spec AND THEN pay for the engineering AND the cost of your thing, or:

b. you have to convince the OEM that they really need your thing to fulfill the spec they already have, for some reason.

In either case, there's a fair economic disincentive for the OEM to use your thing, it's usually in their best interests (for reputation, profit margin, IP rights, etc) reasons to fill that spec with their thing, or the thing of someone they already have on contract.

So, you've been warned.

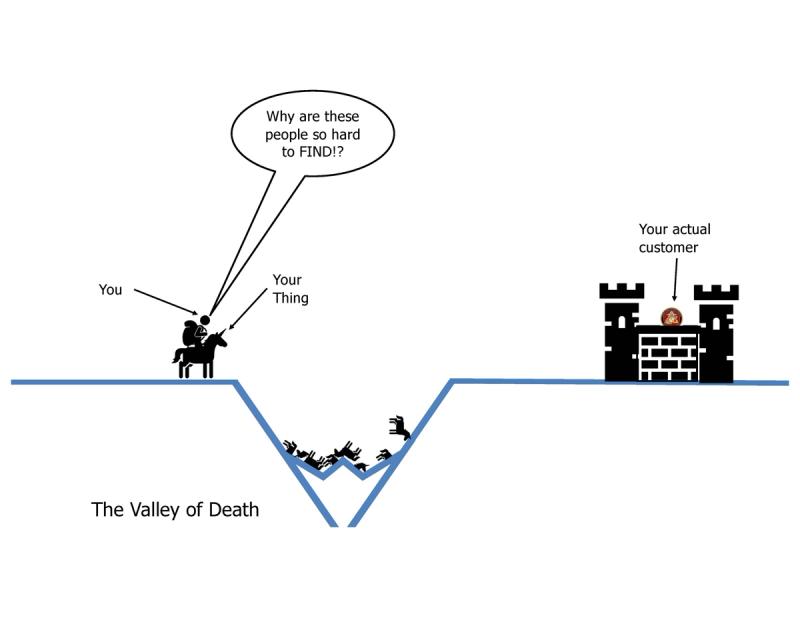

So let's get down to brass tacks, I'm here telling you that you need to go talk to PMs in program offices, right?

But guess what, they're not always easy to find.

SOME OF THEM:

- Put thier phone numbers in their email blocks

- Go to conferences

- Respond to emails

- Answer the phone when their local small business advocate calls them

- Host industry days

- Seek out meaningful conversations with industry

But not all of them.

Why?

BECASUE THESE PEOPLE ARE BUSY!

Also, you and 1,000 of your competitors are constantly calling, emailing, and trying to corner them at conferences. Have some empathy, these people have demanding jobs.

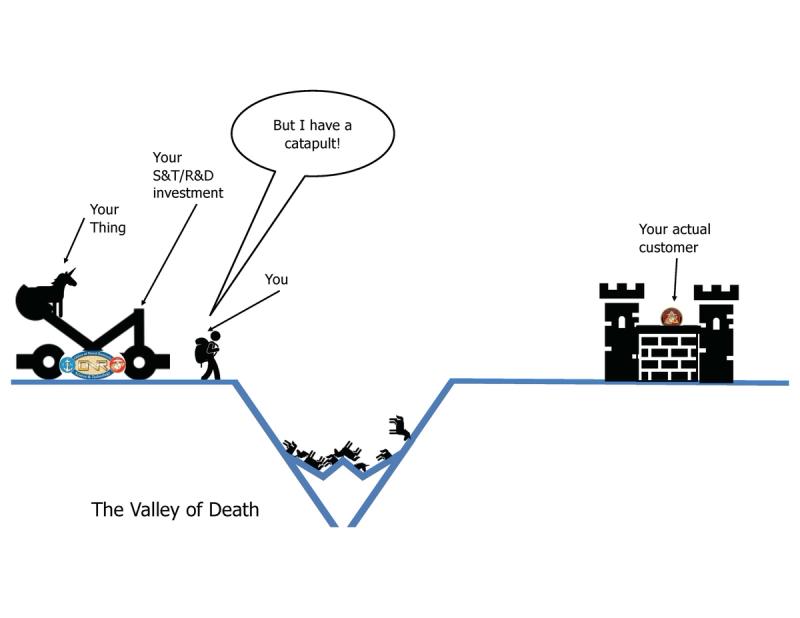

"But I have a catapult" you say, you got some whiz bang S&T money, your R&D PM bought down all the risk, you're TRL 9, they would be foolish not to take your stuff, it's practically free chicken.

I love your energy, but lets talk about that...

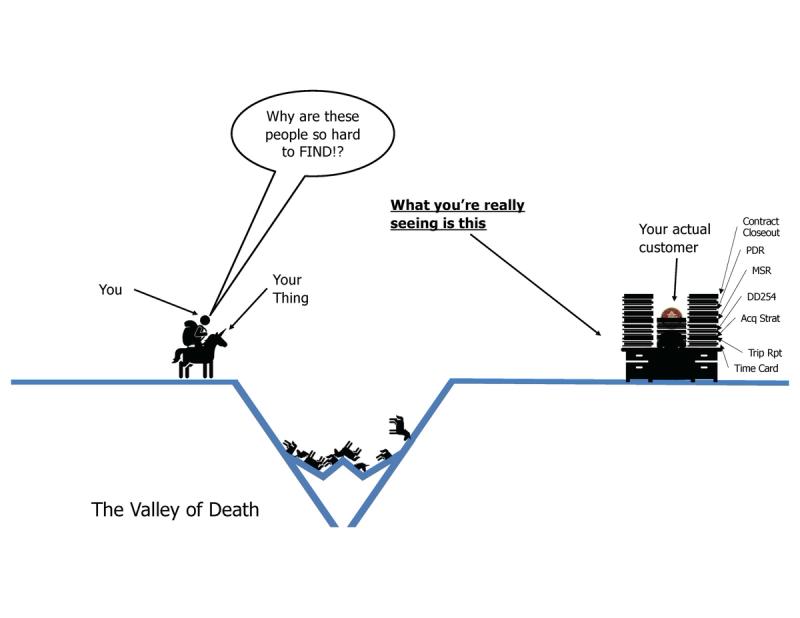

Understanding Your (Real) Customer

Lets talk about your actual customer, the Program Manager, the person who’s job it is to “own” a particular piece of technology, to oversee the requirements development and validation, look for updates and upgrades to their thing, budget and fund development, delivery, training, the whole thing.

They are often hard to get a hold of, some of them don’t put their phone numbers in their signature blocks (yeah we notice), they may not attend conferences, they may be elusive at industry days, some of them seem downright reclusive.

Again, have some empathy, these folks have a lot going on. The have delivery schedules, contracts issues, cost/schedule/performance targets, etc. Add to that, many PMs (at least the military folks) didn’t sign up to be acquisition professionals when they joined the military, they may have gone from being a ground pounder or a pilot and by a twist of fate and branch management, found themselves managing the next generation water filtration system.

Now, if you’re doing your job, chances are good that you found some end user, someone who would actually use your thing. You convinced them that your thing is mana from heaven.

Good.

If they actually want to capture that mana, they have to tell someone, they need to express that need to someone who can do someone about it, someone with a budget, and a delivery schedule, someone like a PM.

Now, as we mentioned earlier, not all end users are created equal. MOST have NO IDEA who manages the programs that provide the things they use. It’s not their fault, they have day jobs.

But, if you did your homework, like we suggested earlier, you probably figured out to whom they need to express their needs.

But be forewarned, most don’t know how to express themselves properly. More on that in a minute.

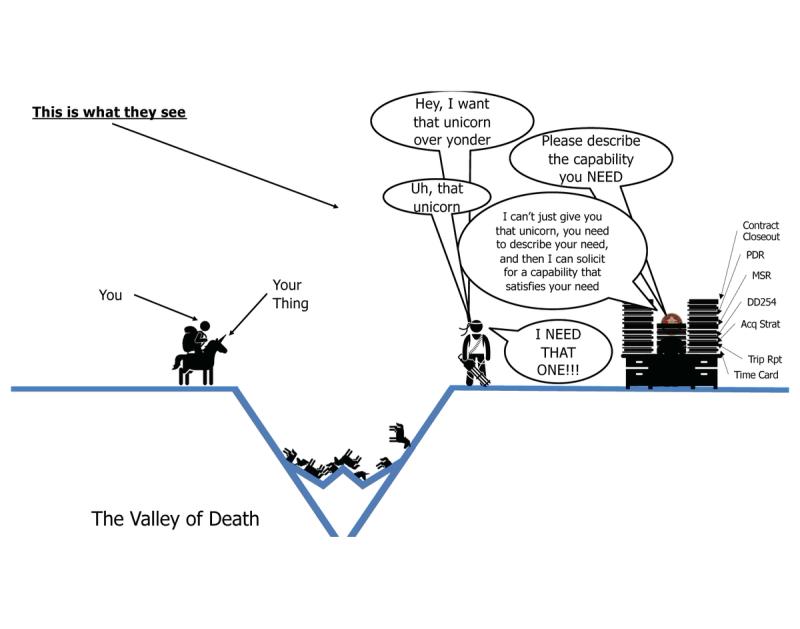

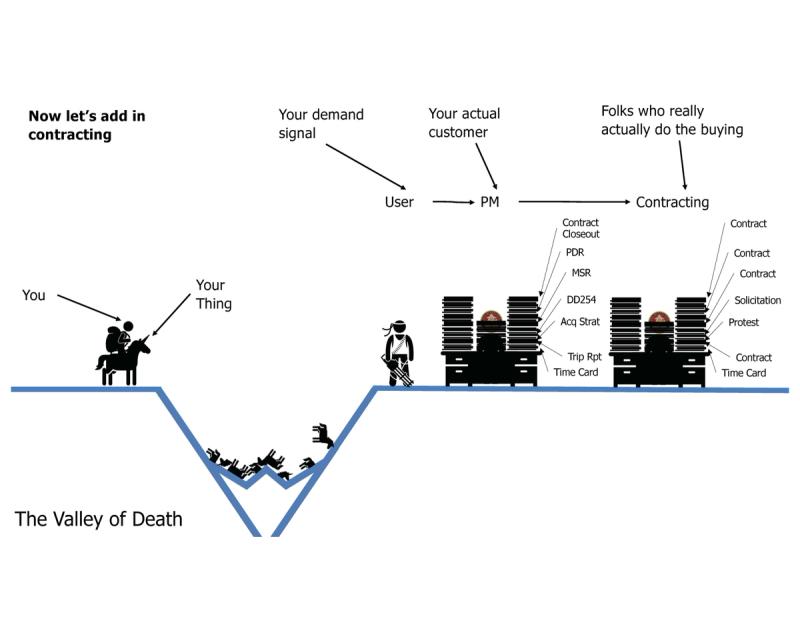

Let us add another level of complexity, the PM does not actually perform the act of buying, they don’t have the authority to obligate the government to pay anything, only a Contracting Officer (KO) can do that. So even if your end user wants your unicorn, and the PM is open to buying it, they have to give their program funding to a KO to actually cut the contract, through which they spend the money. So the PM is the customer of the KO, and the end user is the customer of the PM. See how the layers make things tough sometimes.

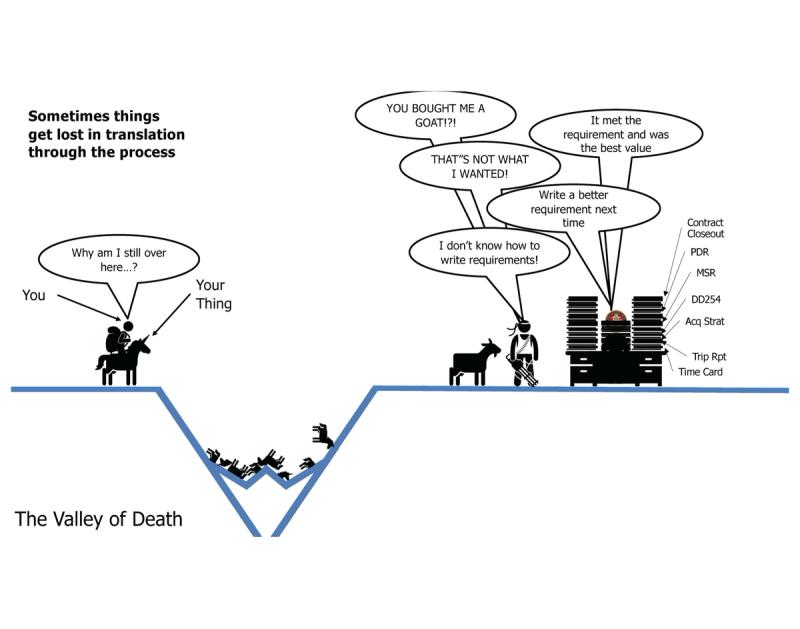

As I said, acquisition professionals (PMs) work with “descriptive” requirements, not “prescriptive” requirements. Your unicorn may be the best on the market, it may be the best value for the money, BUT your customer should not ask for your thing, they can’t “prescribe” what fills their requirement, they must “describe” what they require. Ideally/typically they should also describe WHY they need it, in the context of their operational mission, and why they unicorn they have isn’t good enough “I want an Acme Unicorn, Pegasus Model, in blue”. They have to articulate a requirements for a horned equine mode of transportation, with the capability to fly short distances that has camouflage for maritime environments.

To add another layer in the acquisition telephone game, the KO then has to convert that into a solicitation “we want to buy unicorns” document to solicit unicorn proposals from industry. Industry like you.

There are “requirements” and there are “desirements” – and the two are not created equal. If your customer wants you, they need to describe you in a way that you have a good chance of winning the solicitation, and not some who sells something that seems similar. Otherwise, they get what they get and they don’t get upset. Can they write it so hyper targeted that it’s clear that only your thing could possibly satisfy the requirement? No. A decent KO will shoot that down a mile away. (I know, I know, sole source J&A’s, good luck with that).

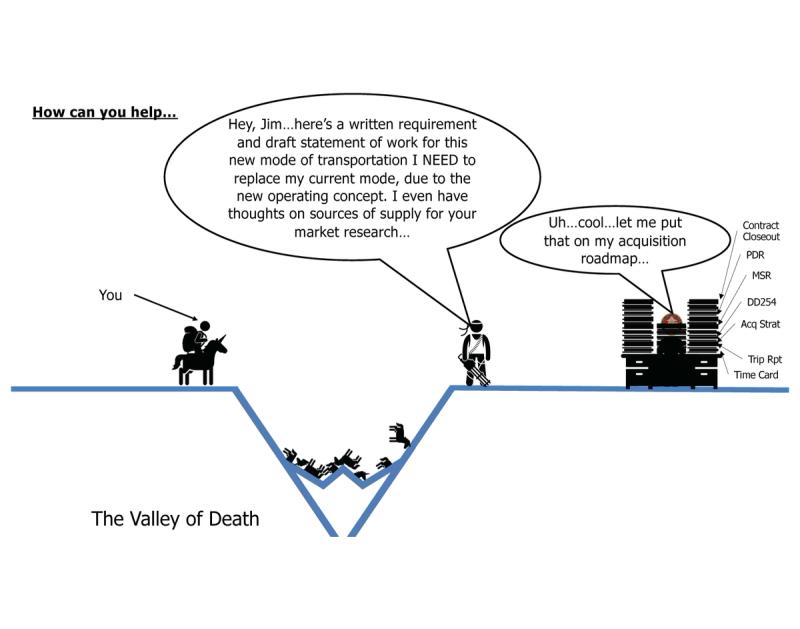

But they can do themselves a big favor by doing the PM a big favor.

But don’t stop there, PMs and Kos have to do a ton of work just to get a solicitation on the street. They need a valid requirement that’s tied to a mission, most of the time they need to justify the new thing (your thing) over the old thing – ideally that it’s better/faster/cheaper. They’ll need to write a Statement of Work or Statement of Objectives for the solicitation, they’ll have to do market research and clear the rule of two and choose a set-aside if applicable.

Guess what, you can do all that for them. You know the end-user’s mission, you know the technology, you know what they’re currently using, you know what the difference is between your thing and their current thing, you know who your competitors are. So package all of that useful knowledge up and give it to them, or give it to your end user to give to them. Save them the time.

Do they have to use your stuff? No.

In fact, if they're worth their salt they shouldn't use just your stuff, they should go out and do thier own due diligence. But if help them get started, you have much better odds of getting what you want.

If you don’t know all of those things, frankly, go figure it out, because that’s just basic business.

The objective end result is to have the PM say “I have a budget for this and I want to buy it in the future.

At this point, you have a target, a base-funded landing point on the other side of the valley.

Is this easy?

NO! It’s hard.

You will probably fail several times before you find a customer/PM who is able and willing to write your thing (or something that sounds a lot like it) into their program plan.

But what’s the alternative?

Be the 97% of tech that doesn’t jump the valley.

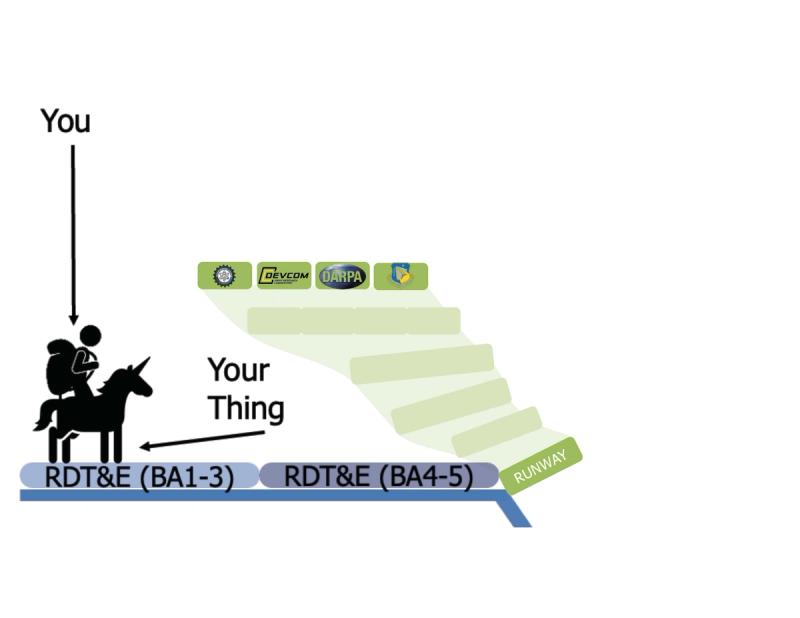

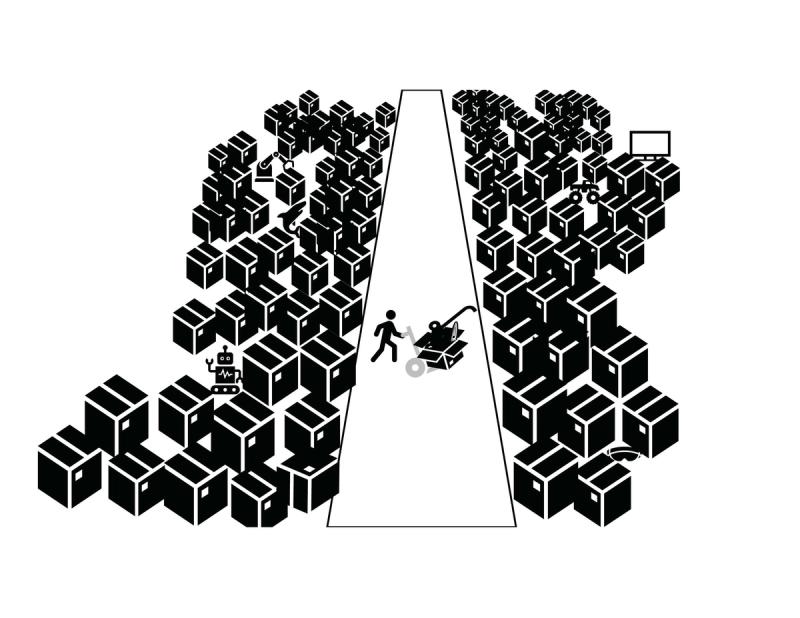

Building Runway

or "no plan survives first contact"

or "don't fall in love with your plan"

or "win by all means necessary"

How do you get over the valley of death?

Well you don't do it by dying on the journey, and by dying I mean running out of money to pay payroll.

This happens more often than you might think, you just don't hear about it. No one walks around bragging about how they quietly shut down their contracting company because they couldn't get a solid customer.

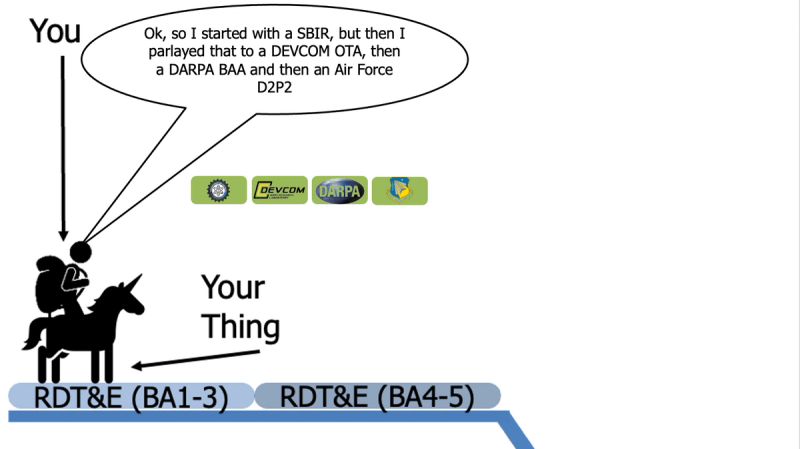

Don't get me wrong, landing a SBIR, OTA, or other research funding is awesome, it is runway you need.

It often offers exposure to potential customers.

It often offers exposure to potential end users.

But if you think a SBIR Phase 1 is going to smoothly roll into a Phase 2 with the same customer, and then they'll love it so much they'll give you a P3...you're dreaming. Don't be too married. to your plan.

But if you think your Phase 1 or Phase 2 SBIR is going to propel you over the valley of death, you are almost certainly wrong.

Why is this though? Why does the government seemingly spread bets around like a squirrel in a casino and then not come back to the table to collect the winnings?

Answer: incentives and objectives.

Half or more of the research dollars spent by DoD are not intended to make a winning bet.

They could be looking for new concepts

They could be creating new foundations for future development

They could be "buying down risk" for someone else to follow behind and pick up the technology

DARPA has something like 7 definitions of "technology transition" and only one of them is to a DoD program of record.

"Then how do I do it???" you ask.

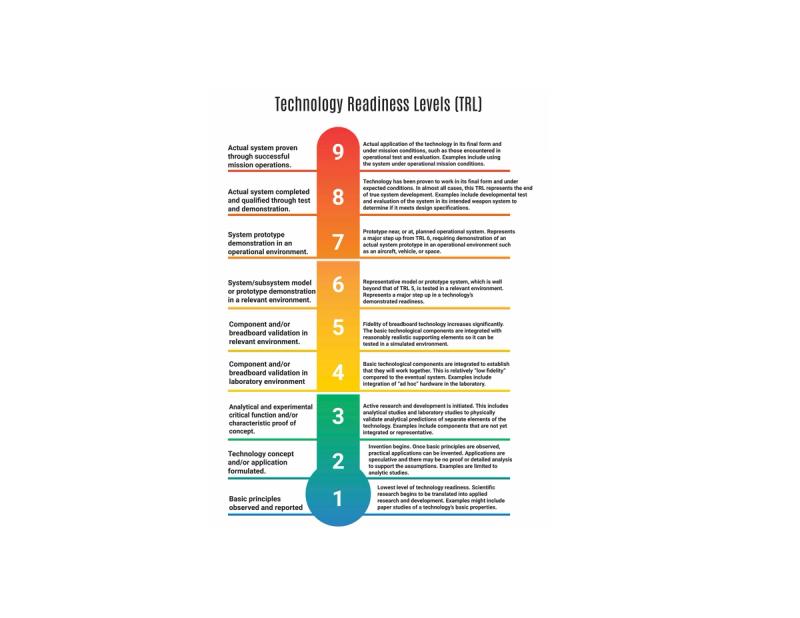

Lets take a step back for a minute and talk about Technology Readiness Levels. This age old metric, originally crafted by NASA is a measuring stick against which your technology will often be judged.

If it's a twinkle in your eye - or a concept on a Phase 1 SBIR white paper - odds are you're at a TRL1.

If you have a fully developed and integrated system that is operational on a mission capable platform, you're more likely a 9.

Why does this matter?

Because there's different colors of research and development money.

Wait, there's colors of colors of money?

Yes, and they're specified for particular purposes.

Your eye twinkle idea should be in the Budget Activity 1 or 2 range of basic or applied research.

If you're thing is a breadboard up to a prototype, it should probably be paid with BA 3.

BA4 is an important one, BA4 money is supposed to take your functional prototype and take it up to an operational prototype.

At the BA5 point you're making that prototype suited for a particular user/mission/system/platform so it can be used, or more importantly BOUGHT.

Why does this all matter?

Not least because that all colors of RDT&E come in the same quantity.

By the numbers, a smart person might want to go after the biggest pots in BA3-5.

But how?

Well, different people can spend different money.

For instance, DARPA doesn't even get BA4 money, they are all in the 1-3 realm. The same goes mostly for the labs, like Army Research Lab and Navy Research Labs.

Air Force Research Lab is a little different, they get a range of different money, but different shops, like materials and lasers probably get more 1-3 money than 4-5.

SOCOM and DIU don't really do much of any 1-3 work, but a lot more 4-5. So different organizations are interested in technology at different TRLs.

If you talk to these folks they'll straight up tell you what TRL they want.

Let's add a wrinkle: funded or fee for service research.

Many of the DoD labs are fee for service, meaning that they receive their funding from the Program Offices.

Wait, what, they're on the other side of the valley.

Think about this, Program Managers need a new thing for a new mission or a new threat, let's say hypersonic missiles.

They have a program, their program has RDT&E funding, because that's how funding is flowed from the Treasury.

So when a PM needs some research done, they throw a MIPR over the fence to the research houses.

What do the research houses do?

They do some internal research, but they also a fund a lot through vendors, like yourselves.

How? Broad Agency Announcements mostly.

They post broad solicitations that stay open for a year or more at a time with categories of things they want to research.

You in turn propose to do said research.

Why is this good, because you're generally working in a development stream that is (at least tangentially) aligned with a program.

Now, are we advocating that you go out, pull a BAA, find a topic that's related to your tech and start lobbing proposals like it's going out of style?

NO!

Go talk to the white coats in the labs and find out what they want. Just like you talk to the end user who is all jazzed about your tech, talk to the labs, rapid tech insertion, rapid prototyping organizations.

The number of organizations that have money and an onus for "innovation" and more importantly investment is growing.

This new DoD site has a good list of them: https://www.ctoinnovation.mil/innovation-organizations

So what are saying? Start with a SBIR or whatever gave you a toe hold, and then broaden your scope and look for other sources of funds, there are many.

Just because you started with a SBIR with one organization, don't hesitate to seek sources of funds in other organizations.

You can chain together sources of funds from multiple organizations to give yourself enough runway to get across the valley.

This also has the benefit of exposing you to more users, more customers, more use cases, more opportunities.

Government investors actually like for their companies to seek and secure investment elsewhere, everyone who puts resources into a technology gets to take credit for it's eventual success, so you are doing the government's work for them.

Why do you need to work on building runway?

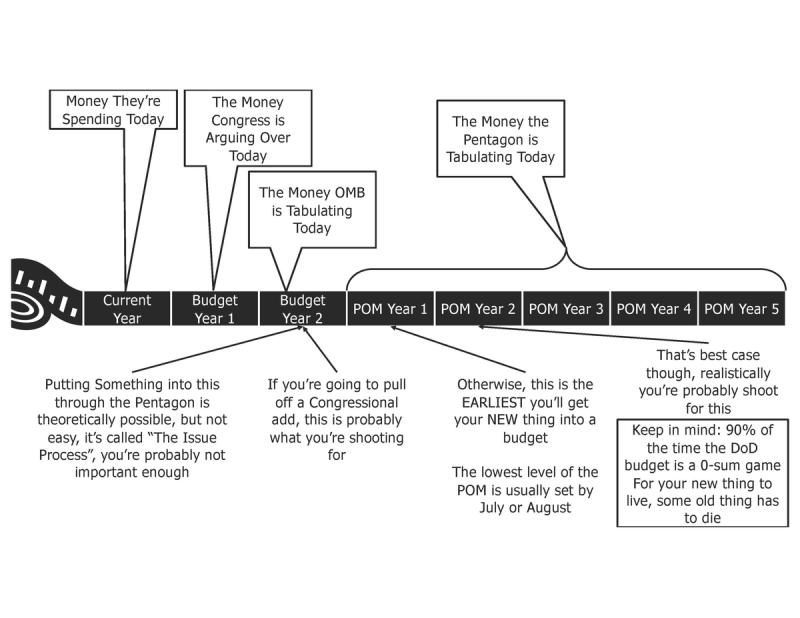

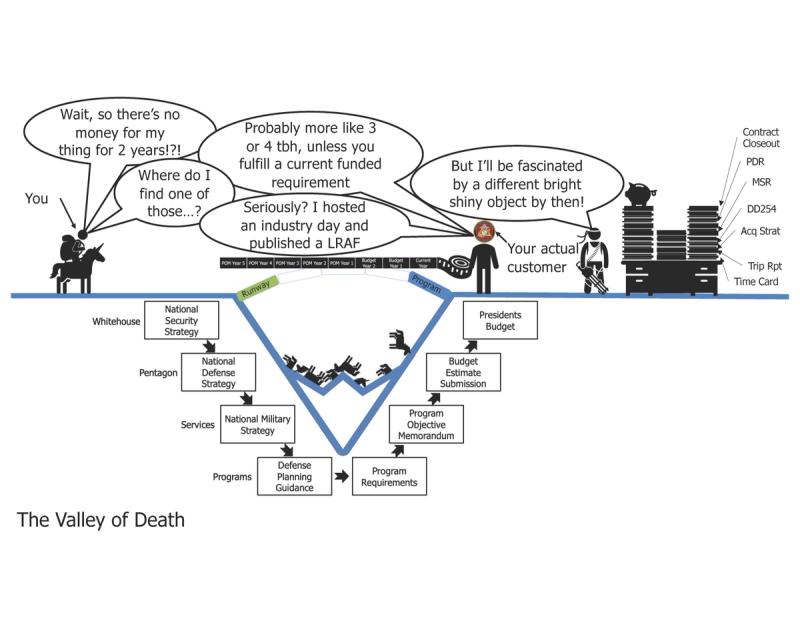

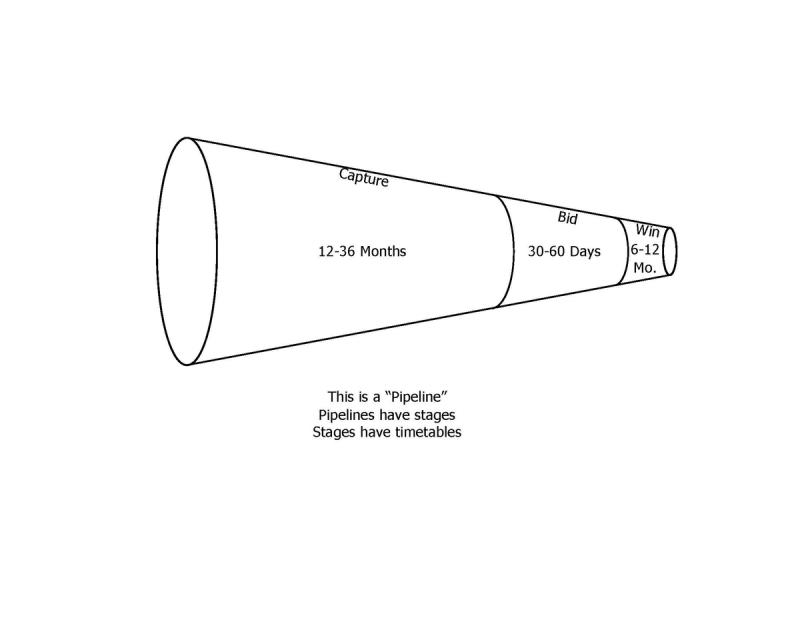

Because you are likely to be on the left side of the valley for 2-5 years, at a minimum. Why?

It's called the POM...

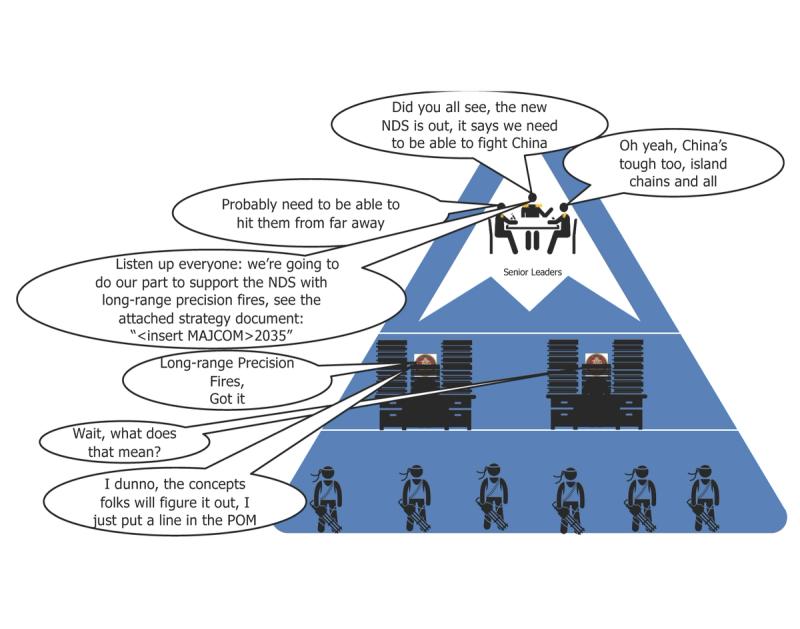

Where Does Program Funding Come From?

Believe it or not, there is not a magical, hidden pot of money laying around the Pentagon, Navy Yard, or Wright Patterson Air Force Base waiting for your awesome thing to come along.

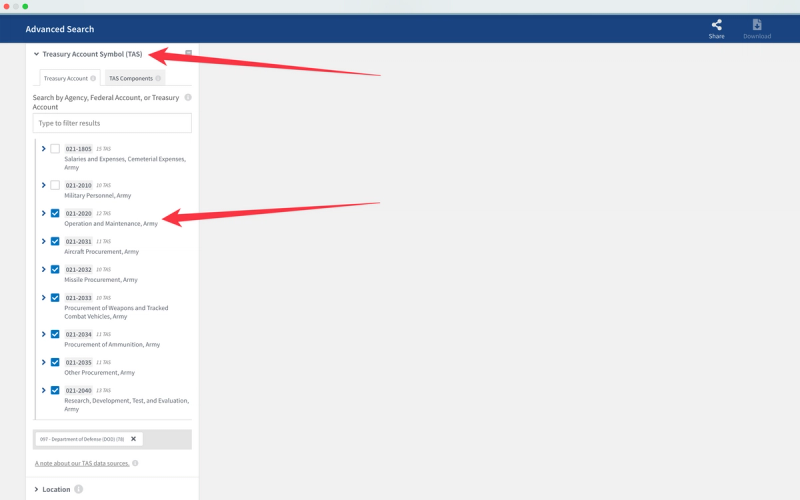

Every red cent is aligned to a purpose, going back to the Program Elements through which money flows like streams, those program elements have very specific purposes.

But wait, what purpose, where does THAT come from?

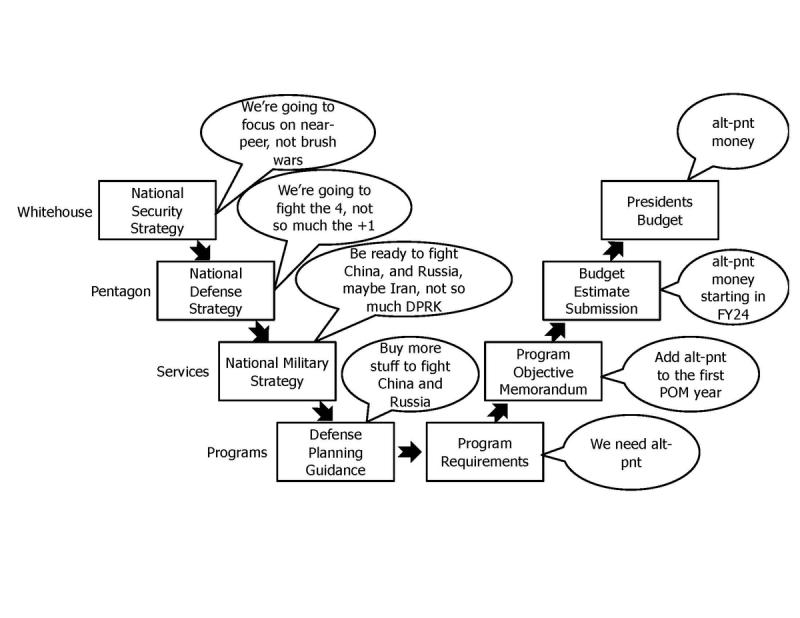

Glad you asked, it's simple, sort of...

The White House publishes a National Security Strategy (Defense, Homeland Security, Intelligence, etc). One of the biggest recent shifts in national security strategy was Obama's "Pivot to the Pacific"

From that, the Pentagon builds a National Defense Strategy, how the DoD is going to do it's part.

From that comes the national military strategy.

From that comes the Defense Planning Guidance - basically instructions to the Department on what they should be spending money on.

From the DPG, program offices start building their Program Objective Memorandum (POM) submissions and their budget estimate submission.

POM turns into BES, BES turns into a budget, budget comes through Program Elements to programs.

So, at the end of the day, every dollar that is spent in the Pentagon on research and development, operations and maintenance, procurement, military construction, or military personnel, flow down from the White House.

This all makes sense because the President, at the end of the day is the leader of the military.

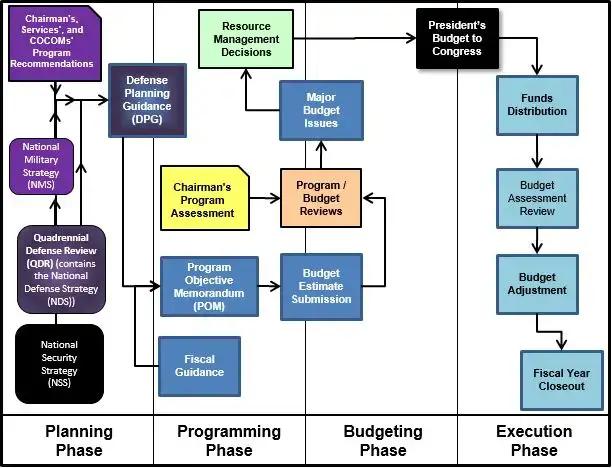

If you prefer a more Pentagonees version of the process, here's a slightly dated view.

There in lies the challenge.

If your thing is genuinely new, never been needed before, then there's a gap in funding where new money had to be "programmed".

The first place to put a new thing is in the first of 5 POM years, which is basically two years form now, whenever "now" is.

In reality, at the lowest program level, POM builds are wrapped up about half way through the year because there are strict timelines for the flow:

- February: Future Year Defense Program (FYDP) Updated

- April: DoD Send Defense Planning Guidance (DPG) to Services

- 30 July: Services submit POM and Budget Estimate Submission (BES) to OSD, CAPE, and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for POM Review (FYDP Updated)

- October – December: Joint OMB-OSD review leading to Resource Management Decision (RMD)

- December: DoD Budget Request sent to OMB

- 1st Monday of February: Presidents Budget due to Congress

Now, keep in mind, that's the "programming phase" of things.

Once a program gets money, they have varying timelines in which to spend the money.

O&M burns the quickest, MILCON burns the slowest, this is why you hear apocryphal stories about government folks spending money quickly at the end of the year to buy TV's and lawn mowers to "burn it" before they "lose".

Now, in some cases this can be an opportunity for folks who know a customer, have a good reputation, and have contracts that can receive funding. If there is funding at the end of the year that needs to be spent, and you have a way for them to spend it, you could be the beneficiary of "end of year money".

So...you find a customer, who has a program, who has a budget, so you can get some of it, right?

Not really. There's "requirements" that budget is supposed to fulfill.

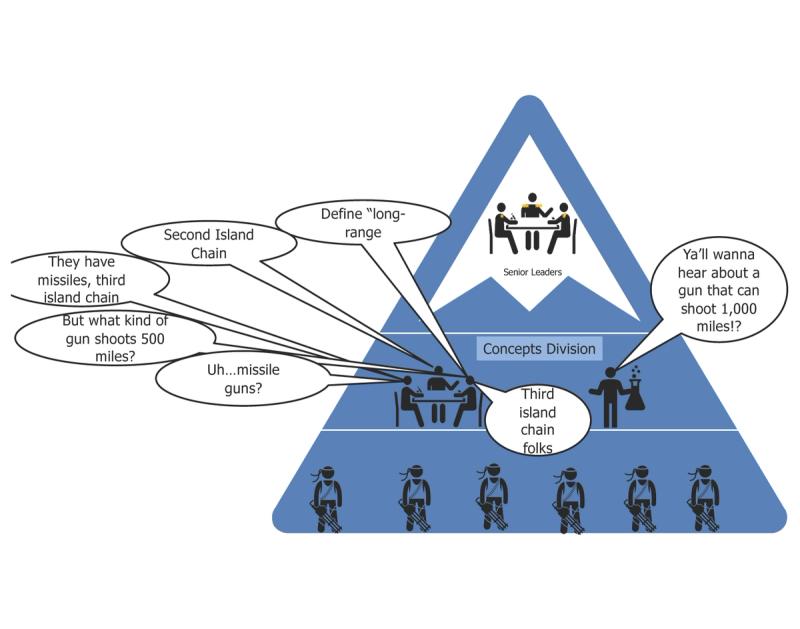

Let's talk about how these requirements come about.

Let's skip the Chart and the whole JCIDS process, we'll stick to the high points.

The NSS, NDS, NMS come down from on high, subordinate commands often develop thier own relevant strategies for how thier force structures will support the strategy.

There's typically a concepts division, like MCWL or ARCIC that tries to translate that vision into tangible operational approaches.

Those operational approaches have "capability" requirements, which translate into technology.

Those concepts flow down to the end users who will inevitably need to use the capabilities to implement the operational concept to fulfill the senior leader's vision.

So, your -customer- the program officers have to translate those capability requirements into things they can request from industry.

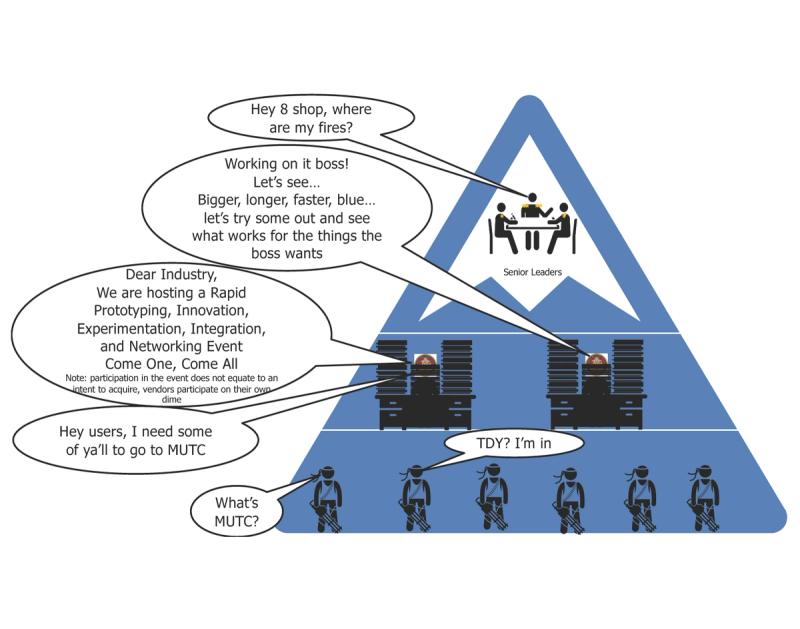

Often times they need to do market research, the FAR actually requires it. Further, they often don't know what sorts of technology is out there to satisfy the stated capability requirements.

In many cases these days they'll do this market research in real life at experimentation exercises where vendors can put up or shut up and leave the slick sheets at the door.

You got invited to a SOF-TE, Trident Spectre, NavalX, Project Convergence, etc, etc. Cool.

-----They hold an experimentation exercise-----

-----They hold an experimentation exercise-----

You MAY have put your product in front of a customer and/or a relevant operational end user. But results may vary, the people who get sent to exercises are not always your customers, or users, they just interested, or had nothing more important to do.

End users are often important participants in these exercises because they have to give feedback to the program offices on what they saw, what they liked, what they didn't, etc.

The program offices translate that feedback into refined requirements that they can in-turn publish in solicitations.

Even then, they typically go through the whole RFI->DRFP->RFP flow.

Why?

Honestly, part of it is the "rule of two", but also because it cuts down on protests. No matter how long the pre-solicitation process takes, it often pales in comparison to the protest process.

At the end of the day, you can get upset that the process takes soooooo long, or you can look at it as the game it is and learn how to play.

You may also be better served by a current requirement, that has funding in the current and next two budgets. What's the down-side? You have to compete, either against the incumbent or all of the other people who are going after the opportunity.

It's up to you, tailor your tech to a current requirement, or try to get a PM to wedge you into a future POM and extend your runway to get you there.

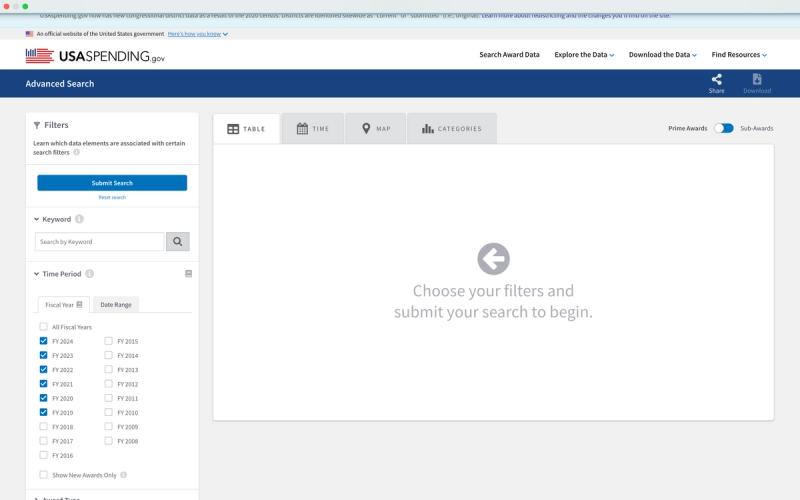

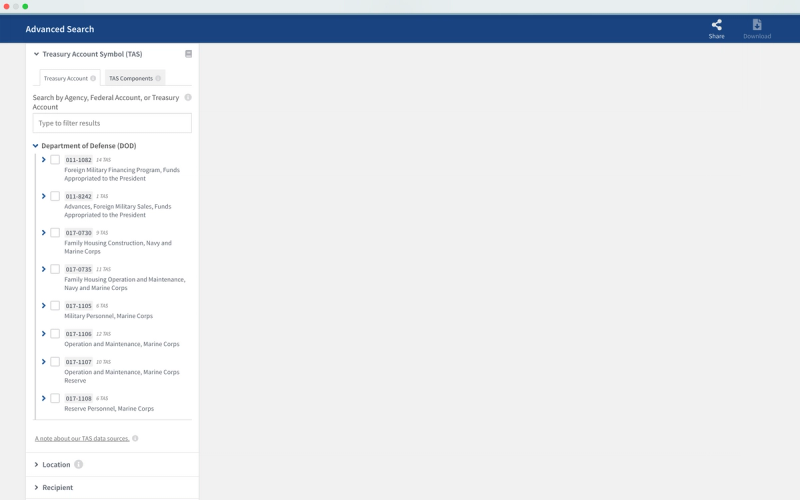

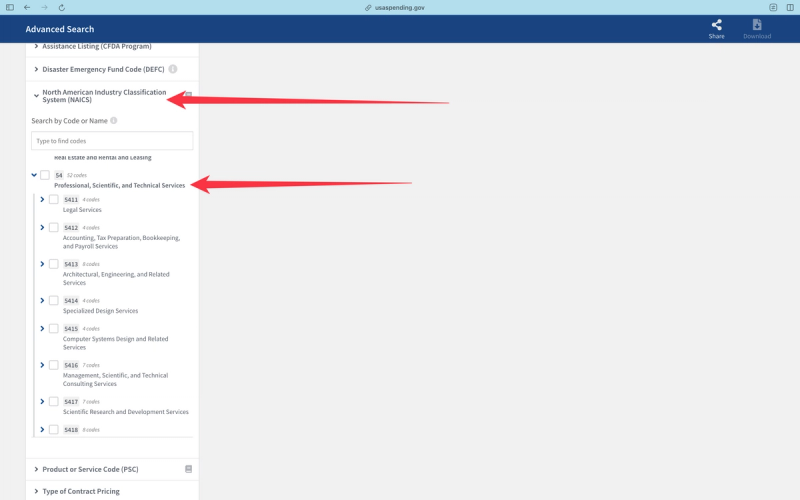

Regardless of your approach, you need to identify what funding you're going after.

Note: There are a multitude of people in the "innovation ecosystem" that neither money nor and influence over money, beware of wasting time with them.

Shortcuts in GovCon

Not to get too philosophical here; the age old Murphy's law rings true time and again:

"The easy route is always mined"

Does anyone like the time it takes to move money through the gears of government?

No.

No one.

Not the users or the vendors, not the leadership or even the folks in the middle. But it's there for a reason, like it or not.

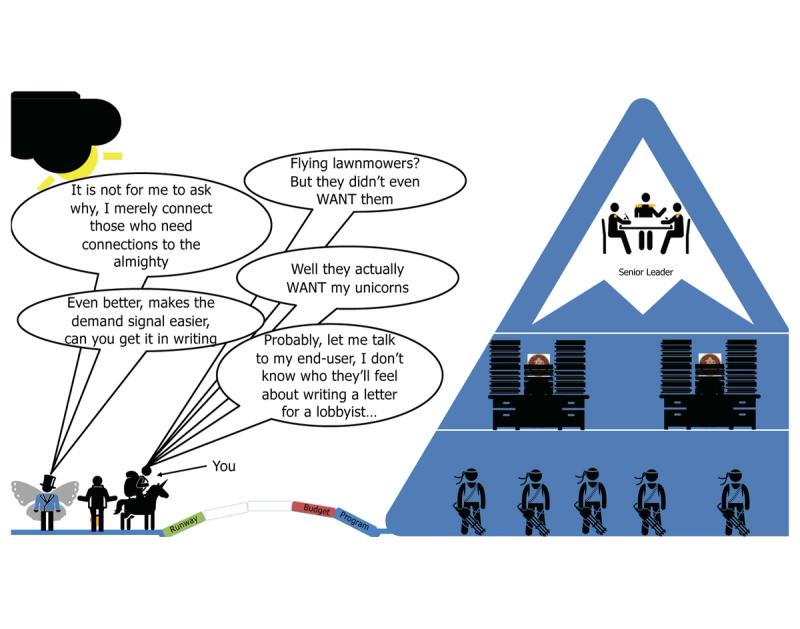

That said, there are a multitude of folks in the ecosystem offering shortcuts to success.

Not, let me be clear: nothing is a monolith, there are a lot of great folks doing great advisory work.

Another note: I fully support the folks who spent their entire lives - from their 18th birthday until they were a stone's throw from social security - serving their country becoming advisors to companies who are trying to understand bureaucracy they spent thier lives living in and leading.

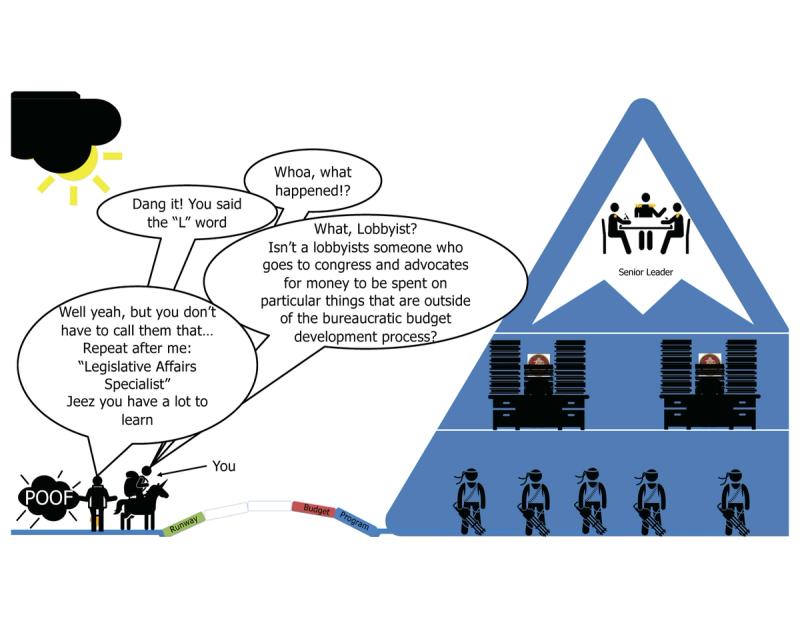

We're not throwing shade, but the uninitiated should know what WRONG looks like, so they can avoid it.

note: if this offends you, now might be a good time for self-reflection.

Folks who retie from the military, whether they were "green suiter" uniformed service members or DoD civilians have a lot of two things you don't:

1. knowledge of the mountain

2. relationships with people you want to talk to

A lot of these folks can directly call up their peers who are still serving, folks they went to school with, perhaps they worked together.

This is not a bad thing, it can be great for connecting with an important segment of the DevBurOps cycle.

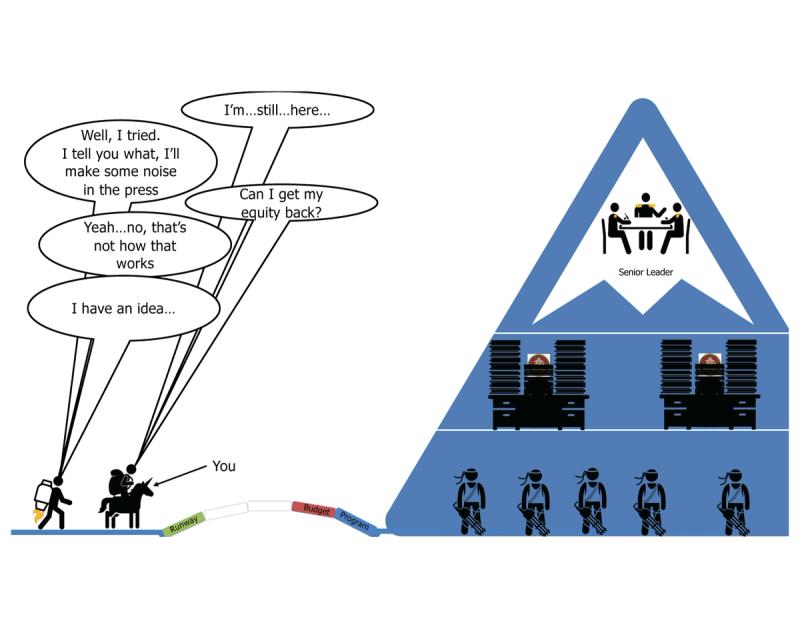

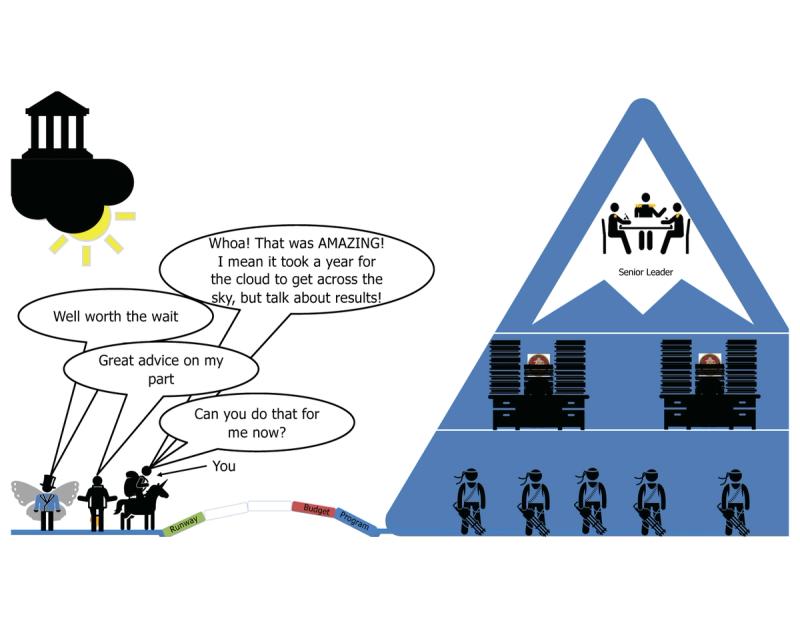

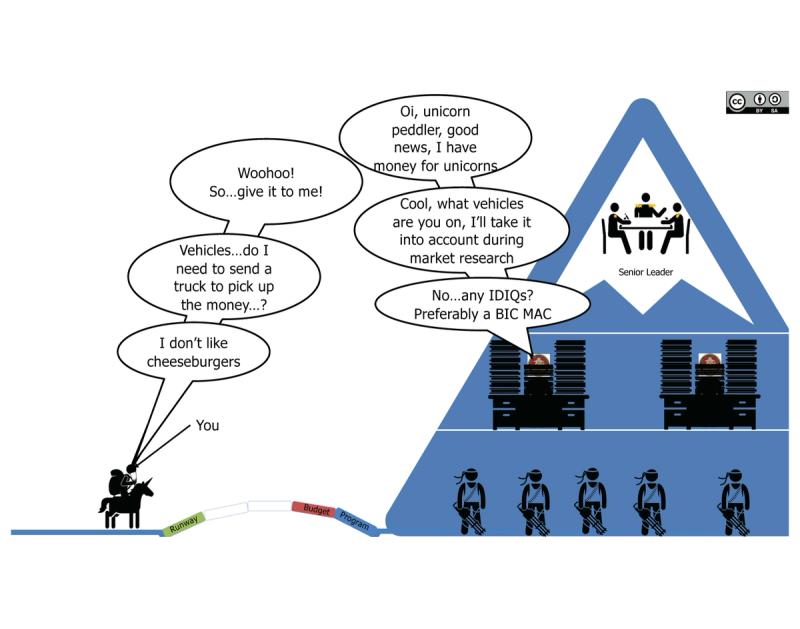

The issue comes when you think you're going to jump straight over the valley, lock in a GO/FO ("go-foe") and get the senior pull to drive budget allocation and user adoption.

Going back the sequence diagram at the beginning of this guide, going from the bottom of the mountain (users) to the top of the mountain (senior leaders) has an adverse effect on your esteem with the middle layer folks.

Here's the thing, GO/FO/SES type rotate (enter and leave the job) every two years, on average.

So, think about that in reality, imagine you just took a new job in charge of 1,000-10,000 people.

It takes about 3-6 months for them to get their feet under them and figure out what's going on.

At which point they are ready to take some action on their strategic plan, which each should have if they're in charge of something that big.

They have about a year to make SOMETHING happen.

Then they're 3-6 months away from either retiring or moving to their next gig and they "don't want to make decision for their successor", meaning that they don't take action that they won't see through. Which, frankly is pretty fair.

At the end of the day, the consultant get's thier due either way.

There's a few ways consultants get their due:

1. Retainer - you plunk down green and they work on your behalf

2. Fee - same as 1. but you pay per cup of coffee

3. Equity - you give them equity and make them a "board member"

In each case the incentives are never totally aligned, except maybe #3, in the case of #3 they are seldom board advisors to only one board at a time, so watch the diffusion of political/social capital and time/attention span.

AGAIN: nothing is a monolith and there are PLENTY of folks who do this well and above board. There's other that don't, don't be enamored with people who have fancy "Former <insert title here>", do your homework.

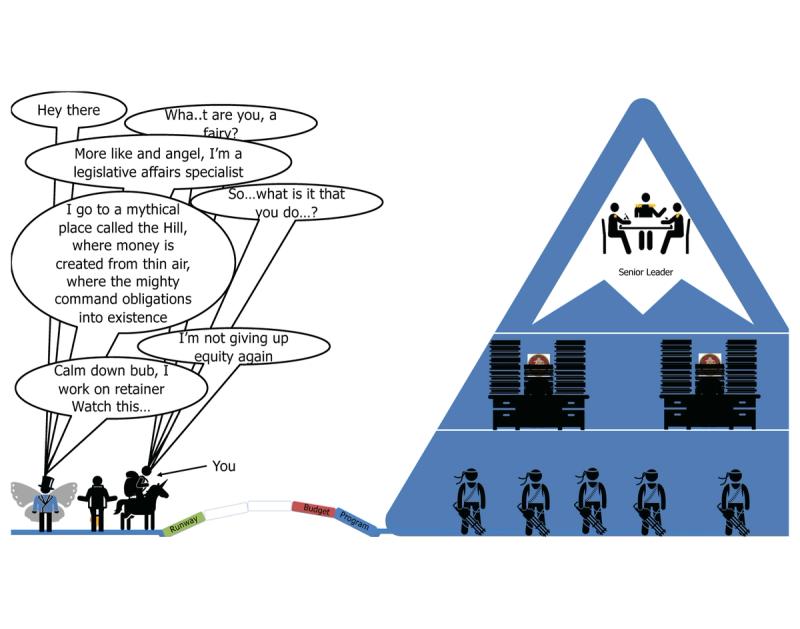

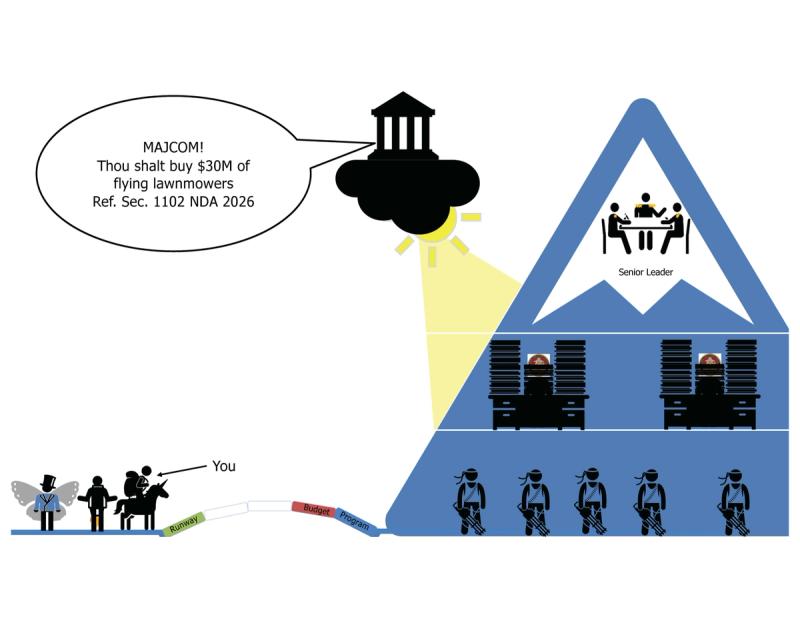

Now, let's talk about another common feature in the space; the legislative affairs specialist.

I'm not here to stand on a pork barrel soap box, there's good reason for Congressional "earmarks", I'm just here to share the facts:

First, you want to deal with the House of Representatives. Why?

Power of the purse.

I'm not here for schoolhouse rock, if you don't know what that means lmgtfy

Within the House, you probably want to focus on one of three committees:

HAC: https://appropriations.house.gov/membership-118th-congress

HASC: https://armedservices.house.gov/

HAC-D: https://appropriations.house.gov/subcommittees/defense/defense-subcommittee-members

All you have to do is:

1. Find a Congressperson in your district, or a district in which you have interests, or could have interests, or impact. (if you are not so lucky...sorry)

2. Go to their site.

3. Look for something like "earmark request", like this: https://mikerogers.house.gov/services/earmark-requests.htm

4. Fill out the request and submit...

You have to get this done early in the year, ideally before the bill gets out of subcommittee.

Want an idea about what you need to submit, most of it is in the open, check it out: https://mikerogers.house.gov/uploadedfiles/component_rebuild_shop.pdf

Try to keep your ask under 5-10 million the FIRST time.

Now, will you get your earmark? Maybe.

Probably not.

You didn't do any sales.

This is just another kind of sales.

You have to engage with these folks, go to the hill, meet with them in their offices, convince them that your thing is going to bring growth, prosperity, innovations, <insert current hot buzz word here>, to their district while also protecting our troops.

Meet with them in your district when they're on recess.

Or...

Pay a consultant to do all that.

They know the hill, they probably came from there. just like the jet-pack GO can fly straight to the top of the mountain, these folks can fly straight to Mount Olympus and speak the same language, make sure your thing is just what they are looking for with their limited earmarks.

Now, is that money going to immediately come directly to your pocket?

NO!

That's not how this works.

Congress puts, in the next NDAA, a mark that says $$$ is allocated to such and such for so and so.

That money flows down to the Pentagon.

The Pentagon puts it in an account, a Program Element if you will.

So...a little review here: what home work do you think you need to do in order to be successful and have that money flow into your revenue?

That's right!

Find a PM in the middle who has a PE that buys stuff for your users!

Simple. Not easy.

So once again, if you want to make this loop close, you need to engage with your customer.

Some customers (PM's) don't like getting earmark money forced upon them, so you really shouldn't do it...

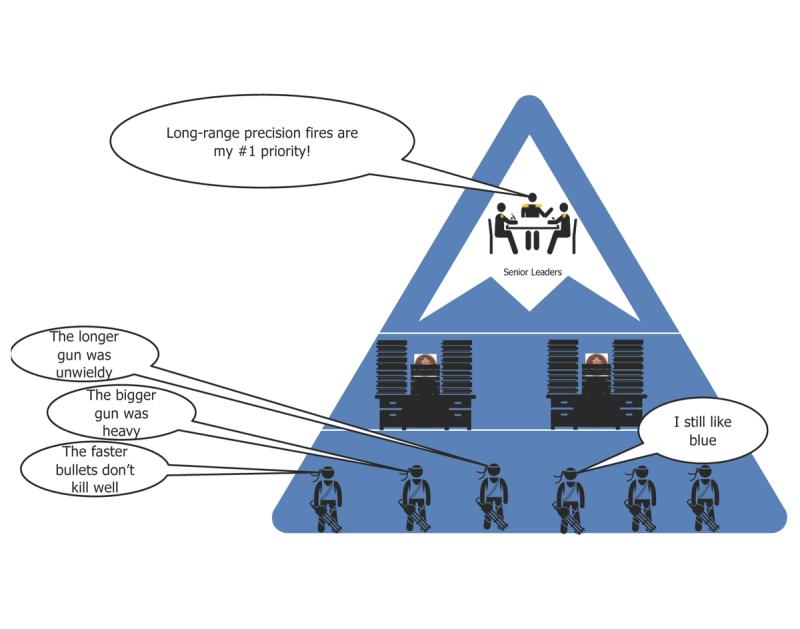

Now, let's be blunt here, anyone who has been the recipient of these good idea fairy, earmark, top-down force downs knows that the following:

1. Getting a first chunk of cash, doesn't mean you'll get a second

2. If you force tech on end users who don't want it, it might backfire over the long run

3. If you throw stuff at the end users and you haven't thought through what happens after it lands in their lap, it probably wont go well...

It might look like this...

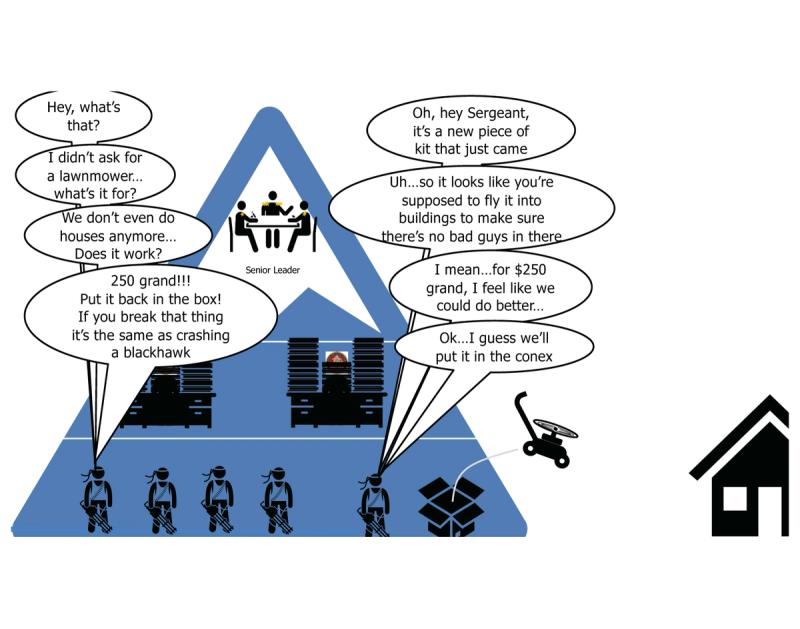

Do you have any idea the ramifications if a servicemember breaks your TRL7 prototype?

Probably not.

But they do.

Have you thought about who, what, when, where, why, and how someone might actually use your thing? like really visualize it. Now visualize it in the cold, rain, sea state 9...yeah...

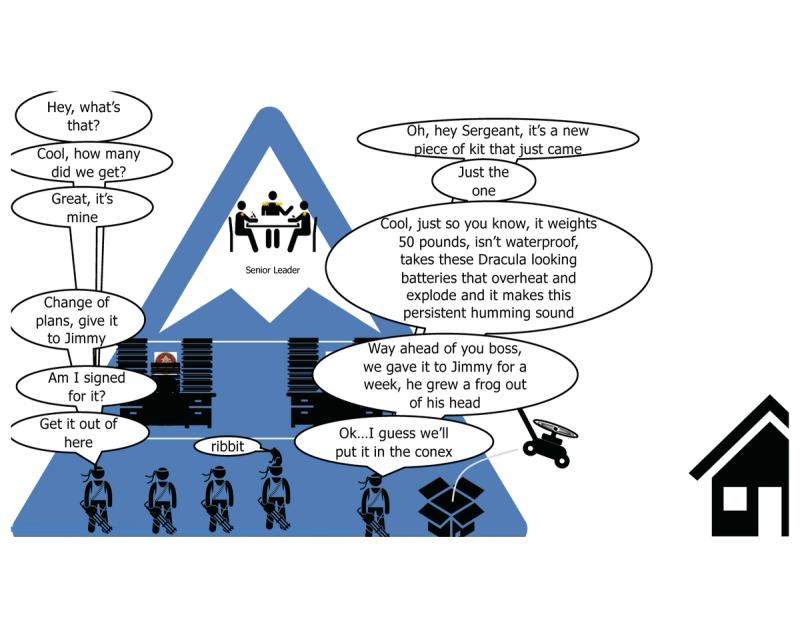

Military folks are used to being treated like lab rats, but after the whole burn pit thing, they're getting touchy about health hazards, so at the very least make sure your thing is safe. Even if it is safe, there's no assurance that product market fit is going to find itself simply because you managed to get some money to flow and some units to get delivered.

If you've never been in the military, you have NO IDEA what kind of shenanigans might go on with your tech. There is no force of creative destruction that rivals a military bored enlisted person on a field exercise or deployment.

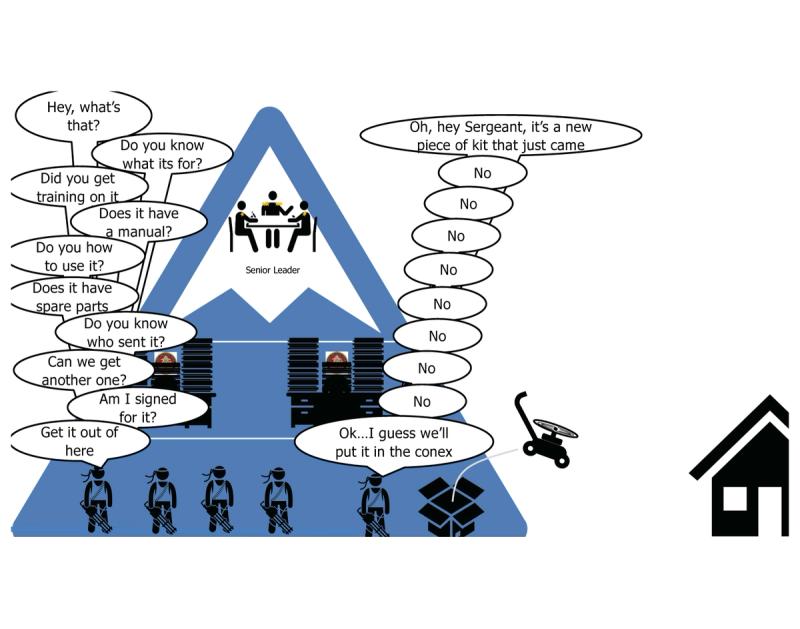

Also, a word for these folks: they don't have a whole lot of time off, or spare time in their annual training schedules.

There is, at any one time, a mountain of things they have trained on at some point in their career, which they may be expected to use at some point in the future, which they only have a foggy idea how to use.

Do your best not to make your thing one of those things.

Think about training, it's always an after thought for vendors.

...at the end of the day, the vast majority of new, nifty, non-standard things end up here, wedged between the holy grail, lost ark, and those smart touch marker boards that someone thought were a good idea 5 years ago.

Take a guess what that does to your annual recurring revenue.

Hint: it rhymes with frown.

Is this all the folks who "work the hill"?

No.

But it is SOME of the people.

So, from the senior leader, customer, and user perspective, how are you different?

How are you not just the latest in a long line of "I built a better mouse trap" vaporware vendors who sought the shortcut to the promised land?

Because you better bet your bottom dollar, they've seen one before.

What's worse: their life and thier ability to do their job may very well have been made worse as a result.

So do yourself a favor:

1. talk to the customer

2. talk to the users

3. think about how your thing can be a bolt-on value add

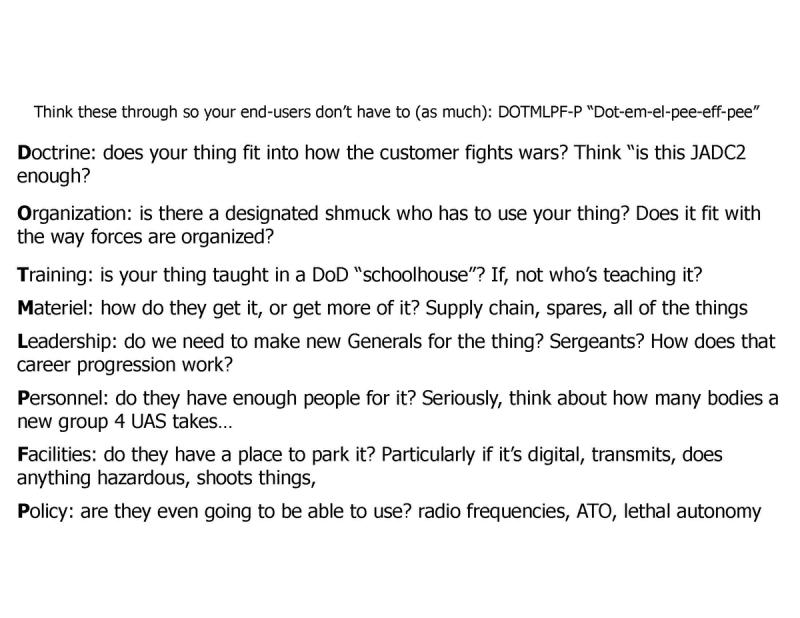

To do #3 , you may want to turn to trusty old DOTMLPF-P!

This is basically ABC's for anyone who has worked in requirements or program management.

For formal acquisition programs, they typically do a full analysis of these factors to assess the impact a new thing will have on the force structure.

Think about it: if the lawn mower peddler had considered DOTMLPF-P, how many of those conex scenarios would they avoid?

Most, if not all.

Also, your customer will likely have to do an analysis one way or another if you want them to buy your thing more than once, so why not give them a head start and at least think about it for them, and have some answers.

You Can't Have Money Without a Contract

An often overlooked, misunderstood, bewildering and opaque art is that of the contract. Sure, everyone knows you NEED a contract, but there's just SO MANY ACRONYMS, and different kinds, and half of them seem worthless from the point of view of a company.

Nonetheless, functionally, the government CANNOT give your company money without a contract (or agreement).

To put a fine point on things, only career field 1102 contracting officers ("KO's" don't ask me why it's K and not C) with a contracting warrant are legally allowed to obligate the government. All others are just people who talk.

Now, we wont dive into the difference between a KO, COR, COTR, etc, let's just stick to contracts and follow the bouncing ball.

As we briefly described long ago in this guide, when a customer (program manager) wants to spend money to buy things for their users, they need a contract.

Some have strong preference of what vehicle, contract type, contract agent, etc, sort of like buying your toothpaste from Target vs. WalMart.

Some are required to use particular contracts per their organization's rules and regulations. These are all things you should figure out.

The bottom line is that PMs are not necessarily paired or assigned 1-to-1 with a KO who's job it is to buy their stuff.

Remember, the PM has the money in their Program Elements for THEIR programs, they may very well use any number of contracts to buy the things they want.

Important point here: smart companies bring work from customers to contracts. If you have a customer (PM) who wants to buy your things, and you're on contract vehicle A but not vehicle B, often times you can convince the PM to buy the things through vehicle A.

Remember the golden rule.

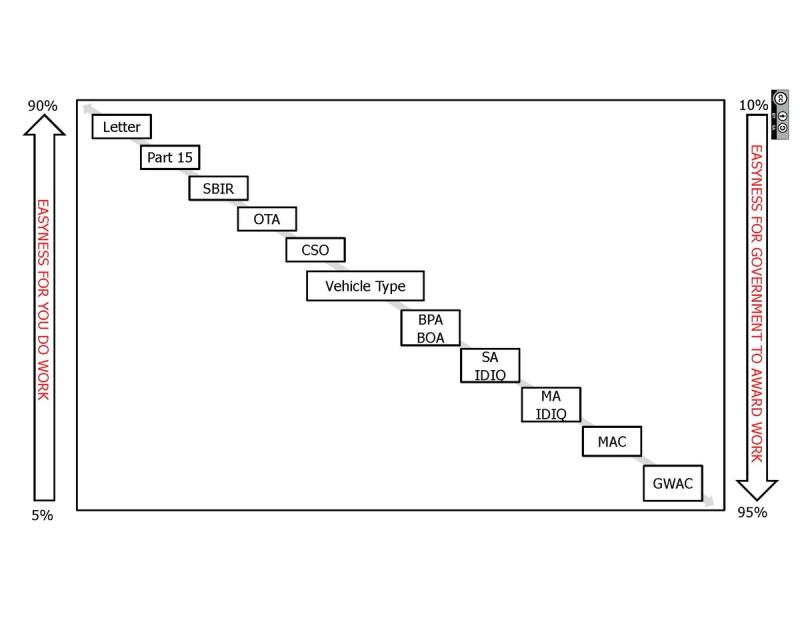

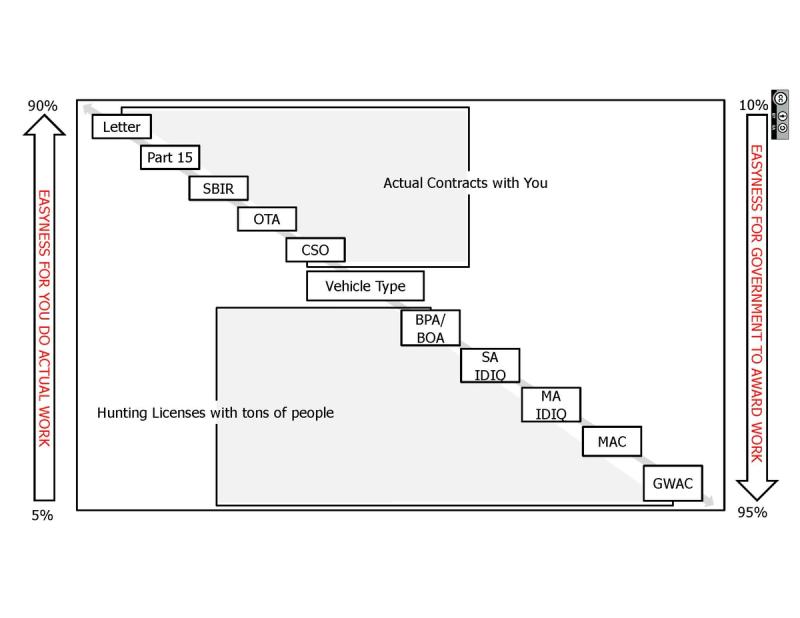

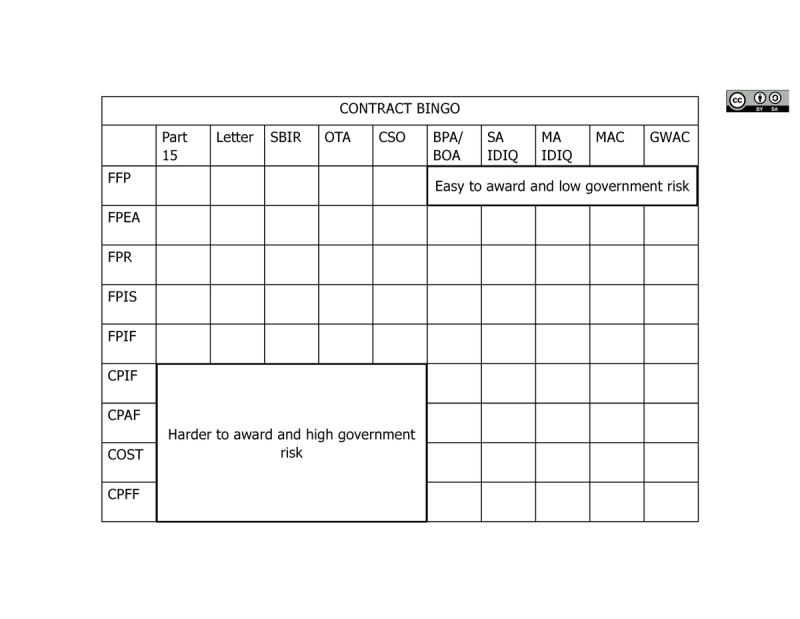

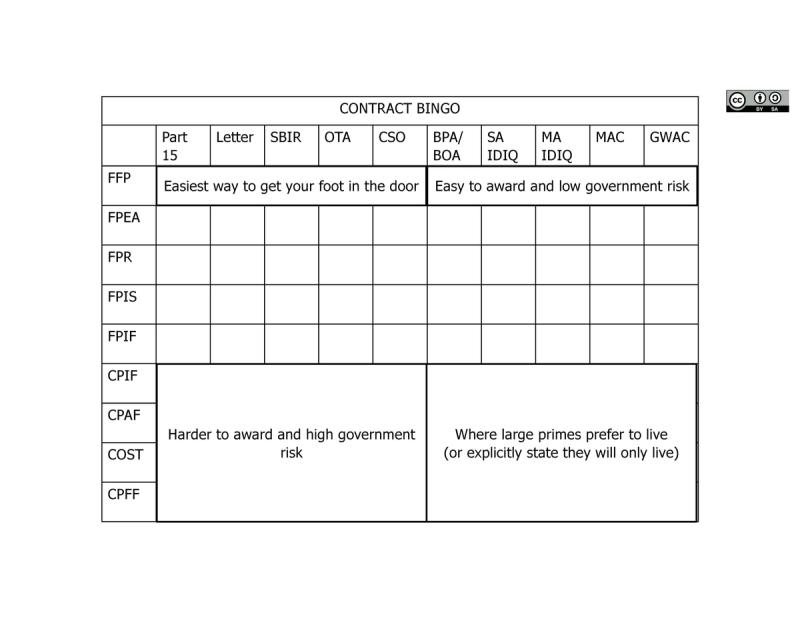

Now, there are a lot of contract "vehicle" types. Some are easier than others to award work on.

All the way at the top is a FAR Part 15 negotiated contract, legit a document written just for you to buy stuff just from you.

On the other end of the buying spectrum is a Government-Wide Acquisition Contract (GWAC) or Multiple-Agency Contract (MAC) like OASIS+, PACTS IV, NASA SOUP 6, etc.

These contracts are with 10's to 1,000's of companies, and are not really money-producing contracts per se.

Things like Blanket Purchase agreement, Indefinite Quantity/Indefinite Delivery, Multiple Award Schedules, etc are just "hunting licenses" for winning work. Just like if you manage to get your product listed on Amazon, you don't magically make sales. That means you have to invest blood, sweat and tears to "get on" the vehicle, and then you have to spend even more blood sweat and tears to actually win a money-producing task/delivery order.

Task order: an actual award to buy services on an IDIQ

Delivery order: an actual award to buy products on an IDIQ

Fun times...

But why?

Because those large IDIQ, MAC, GWAC contracts are easier.

Think about it, it's like having certified vendors for particular goods and services. the based contract vehicle competition takes care of baseline things like past performance, certifications, and in some cases prices.

I liken this to online shopping, I love buying things from Amazon, and I'm somewhat annoyed when a company doesn't sell l their things on Amazon. I have to go to their website, enter all of my address and credit card information, and worst of all, deal with their shipping timelines. I just want to swipe the buy button and know I'm going to get my protein shakes in 24-48 hours. That's sort of the difference between FAR Part 15 contracts and multiple award contracts.

So, when a PM wants to buy something, all the have to do is write the requirement, put it out for bid on the vehicle, and they know that everyone who responds has a certain baseline of capability, reliability, and affordability.

That vs. a FAR Part 15 contract where they have to cast their requirement into the wide open and take their chances with who will respond and then do all their own due diligence on the proposals.

Do you like picking through all of the reviews on Amazon, or do you just go to the "suggested by Amazon" products because you know they'll be mostly reliable? It's kind of like that.

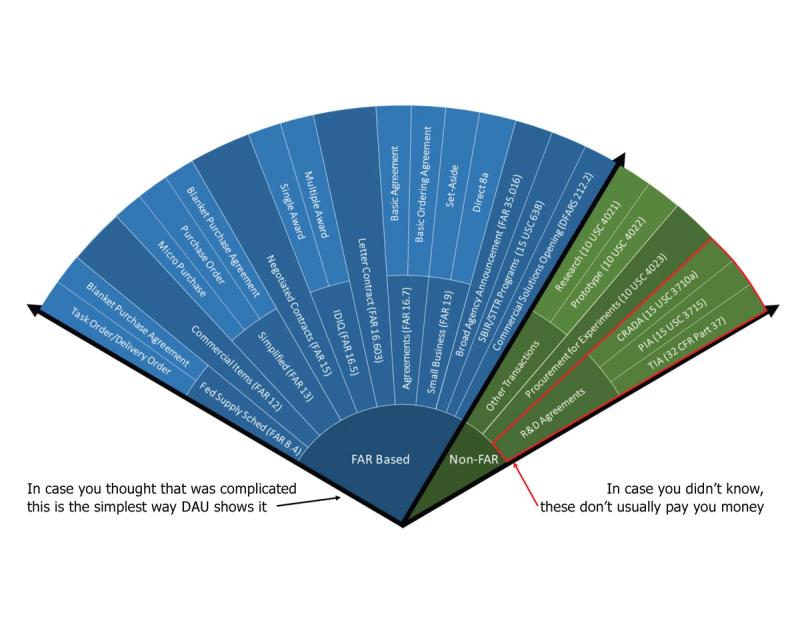

Now let's get the nitty details out of the way about ALL of the various DoD contract vehicle types...

Different vehicles are often used for different things, so knowing the difference can help you target which vehicles you'd like to be on.

- Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA): Think of a BPA as a charge account that the federal government sets up with trusted suppliers. It's used to fill anticipated, repetitive needs for supplies or services. Instead of processing a full purchase each time, the government can quickly order against this account, which streamlines frequent, smaller buys.

- Purchase Order: This is a basic contract where the government orders goods or services from a supplier at a set price. It's the equivalent of a standard shopping transaction but in a formal contract form.

- Micro-purchase: These are small dollar purchases that don't exceed a certain threshold (usually a few thousand dollars). They're made without obtaining competitive quotes, aiming to reduce administrative costs and increase efficiency.

- Task Order/Delivery Order: When the government knows it will need batches of supplies or services over time but can't determine the exact quantities, it issues these orders. They are placed against an existing contract, specifying what's needed at a particular time.

- Commercial Items (FAR Part 12): This type of contract is for buying things that are already available in the commercial market. The idea is to get what the military needs without reinventing the wheel, saving time and resources by acquiring off-the-shelf goods or services.

- Basic Ordering Agreement (BOA): A BOA is not a contract itself but an understanding between an agency and a supplier. It sets terms and prices for future contracts, making the actual contract execution faster and smoother.

- Letter Contract (FAR 16.603): This is a temporary contract that lets the contractor begin work immediately before the formal contract is finalized. It's like a "we'll pay you, start working now and we'll sort out the details later" arrangement.

- Agreements (FAR Part 16): These are varied arrangements that can be put in place for special working relationships or partnerships, like when companies team up to work on a government project.

- Small Business Set-Aside (FAR Part 19): These contracts are reserved exclusively for small businesses. It's a way for the government to support small companies by giving them a fair chance to compete for contracts.

- Negotiated Contract (FAR Part 15): Unlike buying something off a shelf, some military needs are so unique that they require back-and-forth negotiation to settle the terms and prices. These contracts result from that negotiation.

- Simplified Acquisition (FAR Part 13): This method is for purchasing lower-value items. It's a faster, easier process for the government to buy what it needs while keeping the paperwork to a minimum.

- Other Transactions (OTs) for R&D and Prototypes (10 U.S.C. 2371, 2371b): These are more flexible arrangements that the government uses when it needs cutting-edge research and development, including prototypes. OTs are unique in that they are not subject to many of the regulations that govern standard government contracts.

- Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO): A CSO is a modern approach for procuring innovative commercial products, technologies, or services that meet the government's needs, often with more relaxed rules to encourage non-traditional contractors to propose creative solutions.

- Research and Prototype Contracts: These contracts focus specifically on the exploration and initial development of new technologies, systems, or materials that the military could use.

- Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA): Under a CRADA, the government and private companies or academia can legally collaborate on research and development projects, sharing resources, knowledge, and expertise.

- Partnership Intermediary Agreements (PIA): These agreements aim to create partnerships between the DoD and intermediaries like universities or non-profits to facilitate technology transfers and support defense objectives.

- Technology Investment Agreements (TIA): TIAs help the government invest in advanced technologies. They're used to attract and involve commercial firms in military research and development efforts, with a particular interest in innovative technologies not usually developed under traditional defense contracts.

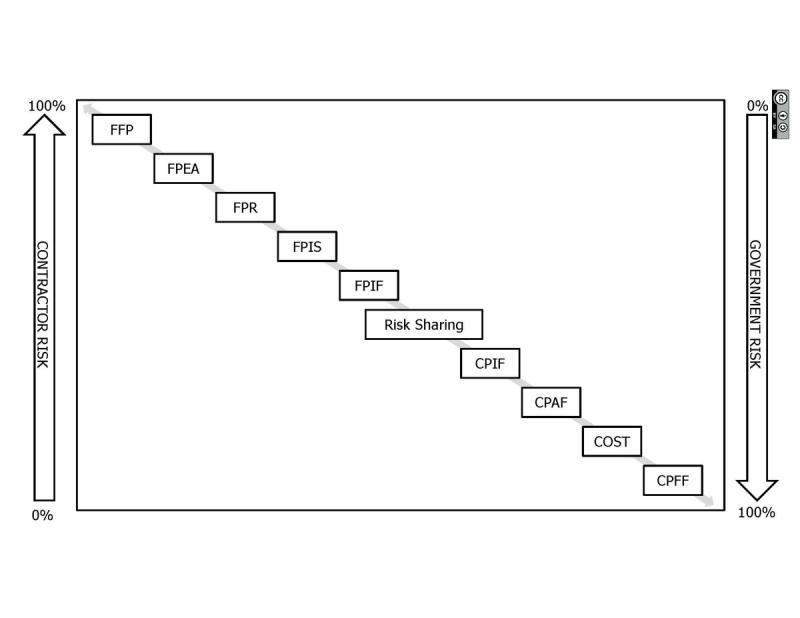

Ok, so that's all the types of contract vehicles, but there's also a ton of different ways that those contracts treat prices and costs.

And the major difference is all about risk.

- FFP (Firm Fixed Price): The contractor agrees to deliver a product or service at a set price.

- Government risk: Low, as the cost is fixed.

- Contractor risk: High, as they bear any cost overruns.

- FPEA (Fixed Price with Economic Price Adjustment): Similar to FFP, but includes provisions for adjusting the contract price due to specific economic conditions.

- Government risk: Moderate, as adjustments can increase costs.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, as it allows for some cost fluctuation coverage.

- FPR (Fixed Price Redeterminable): The price is initially fixed but may be adjusted based on certain conditions defined in the contract. This type isn't standard and might be less commonly referenced, potentially being confused with other fixed-price variations.

- Government risk: Moderate, due to potential adjustments.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, as it offers a mechanism to adjust the contract price under specified conditions.

- FPIS (Fixed Price Incentive Fee): A fixed-price contract that provides for adjusting profit and establishing the final contract price through a formula based on the relationship of total allowable costs to total target costs.

- Government risk: Moderate, as costs can increase if targets are met.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, incentivizes cost control and efficiency.

- FPIF (Fixed Price Incentive Firm): Similar to FPIS, it's a fixed-price contract that includes a formula for final price determination that incentivizes performance on the contractor’s part.

- Government risk: Moderate, as incentives can increase total cost.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, with potential for higher profit if performance targets are met.

- CPIF (Cost Plus Incentive Fee): The contractor is reimbursed for all allowable costs as determined by the contract plus an incentive fee based upon achieving certain performance objectives.

- Government risk: High, as costs can escalate.

- Contractor risk: Low, since costs are covered, plus an incentive for efficiency.

- CPAF (Cost Plus Award Fee): Reimburses the contractor for allowable costs and includes a fee consisting of a base amount fixed at inception and an award amount, given for meeting or exceeding certain performance criteria.

- Government risk: High, as costs can escalate, but controlled by performance criteria.

- Contractor risk: Low, with incentives for performance.

- COST (Cost Contract): A cost-reimbursement contract in which the contractor receives no fee.

- Government risk: High, as all costs are covered without direct profit for the contractor.

- Contractor risk: Low, but lacks incentive for efficiency since there's no profit.

- CPFF (Cost Plus Fixed Fee): The contractor is reimbursed for all allowable costs plus a fixed fee which is agreed upon at the contract's inception.

- Government risk: High, as costs can escalate.

- Contractor risk: Low, as all costs are covered plus a guaranteed fee.

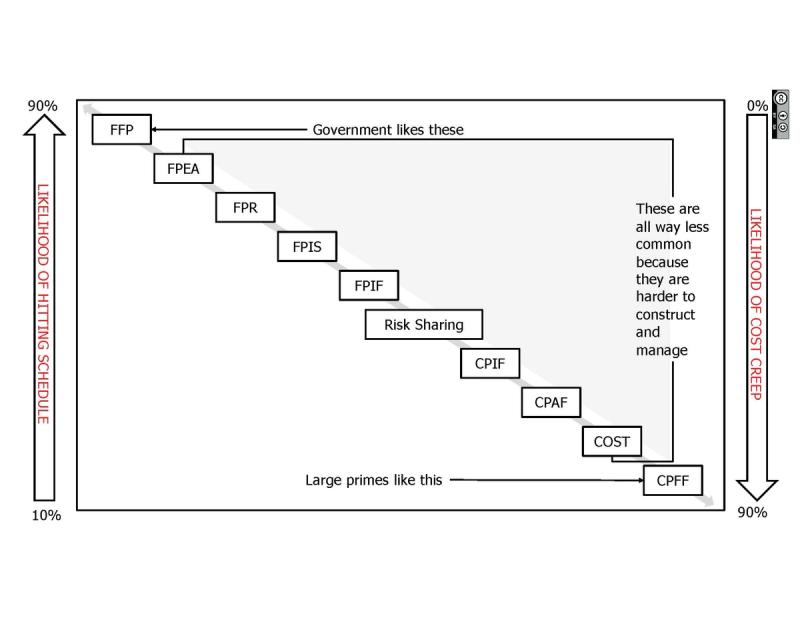

In general terms, the most common contract types are FFP and CPFF.

With the former, the contractor eats all the risk.

With the latter, the government eats all the risk.

Now there is a lot of talk about fixed-price vs. cost-type contracts these days, the big primes are saying they wont even bid on FFP development contracts. Meanwhile the government is very frustrated with cost-type contracts, particularly for large weapons systems that are never on time of budget.

We'll talk a little about why this happens all the time in another segment.

Just take it for granted that cost-type contracts seldom deliver on time and on budget, but hoinestly that's basically what they're for.

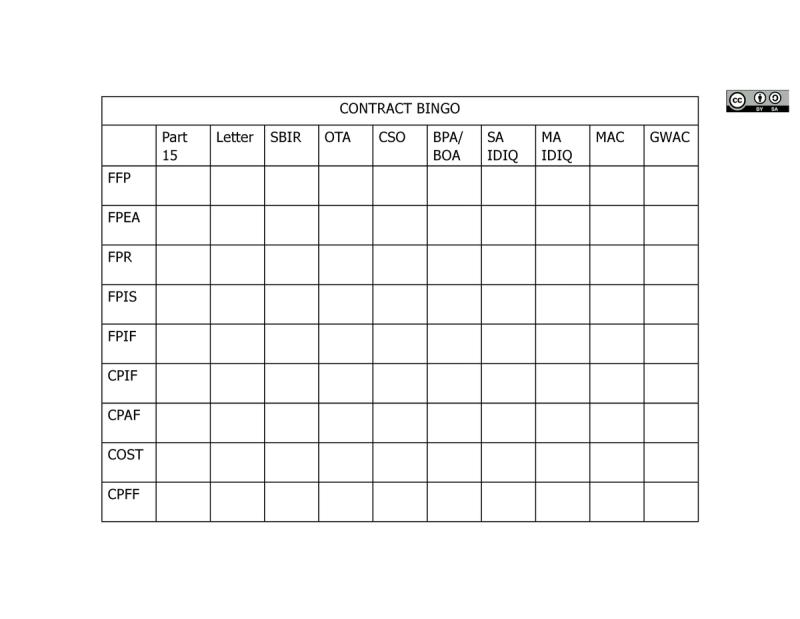

Now, you can sort of mix and match most vehicle types with most price/cost types, though most vehicles only allow for certain types of cost/price structures, so do your homework.

You could easily have a Firm Fixed Price Task Order and a separate CPFF Task Order on the same contract, it's up to the PM and the KO to determine how they want to do it.

Logically, the multiple award and IDIQ contracts are easier for KOs to award, and FFP is the lowest risk.

On the other end, singular contracts of a cost-type are a whole lot more work and much higher risk.

See how we're sort of making an easy/risky matrix here...

So, if you're trying to get your foot in the door, FFP contracts may be the easiest route.

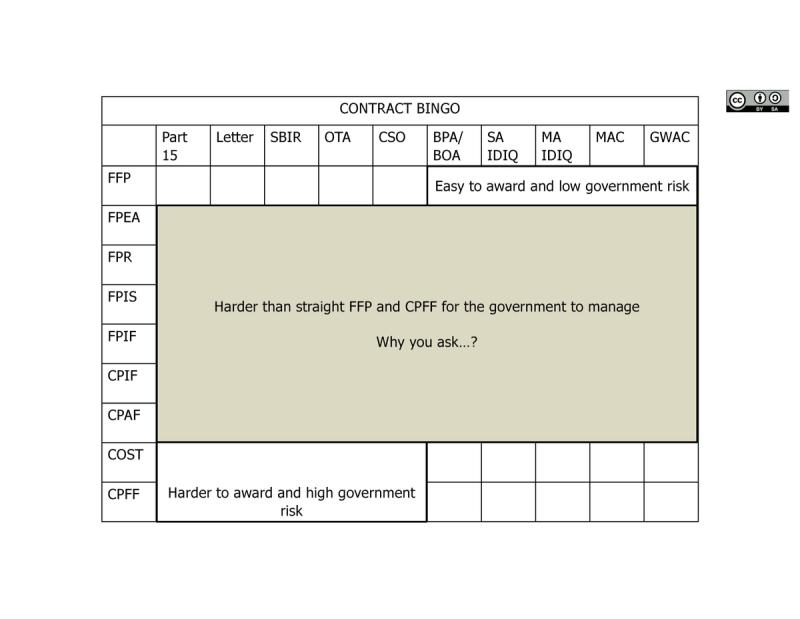

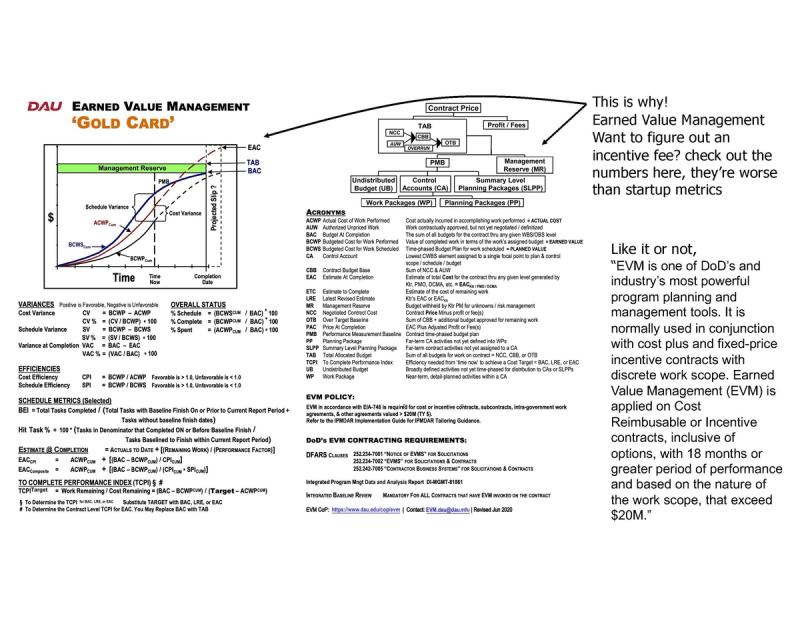

Incentive contracts seem like a great idea, align the profit motive of the contractor with the delivery objective of the government.

However, anything that involves calculating incentives, the government generally avoids having to do, because it's a lot of work and there's often hurt feelings with the contractor when you tell them that their fee is cut for not delivering on time.

And why are they complicated? Earn Value Management!

EVM is almost only used on very large multi-million/billion dollar systems contracts. It's a very logical system, it's just one extra thing to argue over.

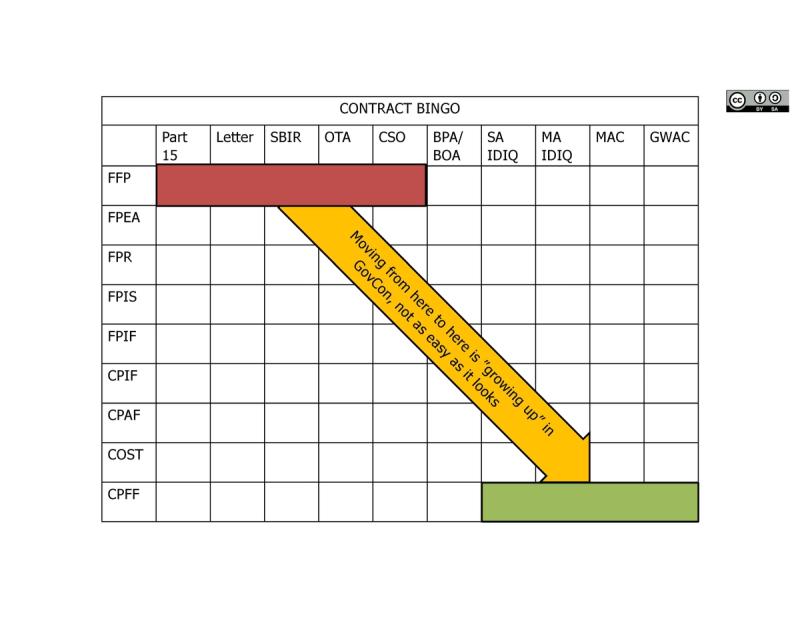

Now, down to brass tacks.

If you're new to the game, you're probably going to have to start in the "hard to award" contract vehicle type with a firm fixed price structure.

As you mature, you'll want to shift to the other end of the matrix, to the easy to award cost-type structures.

If you don't see why, this may not be the game for you.

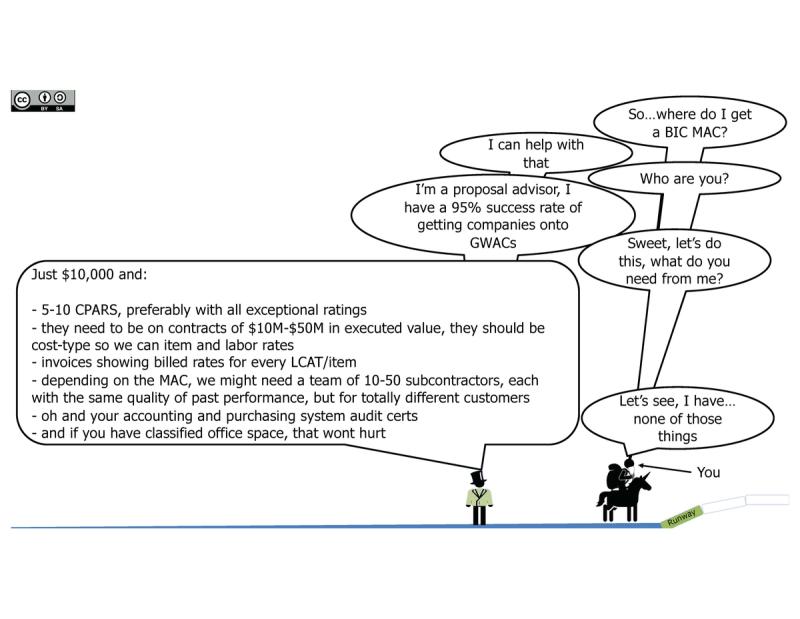

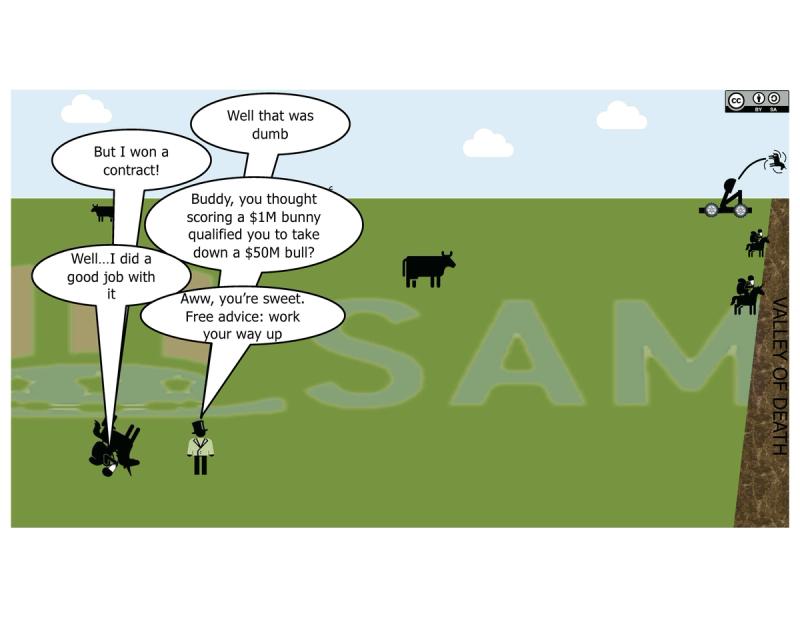

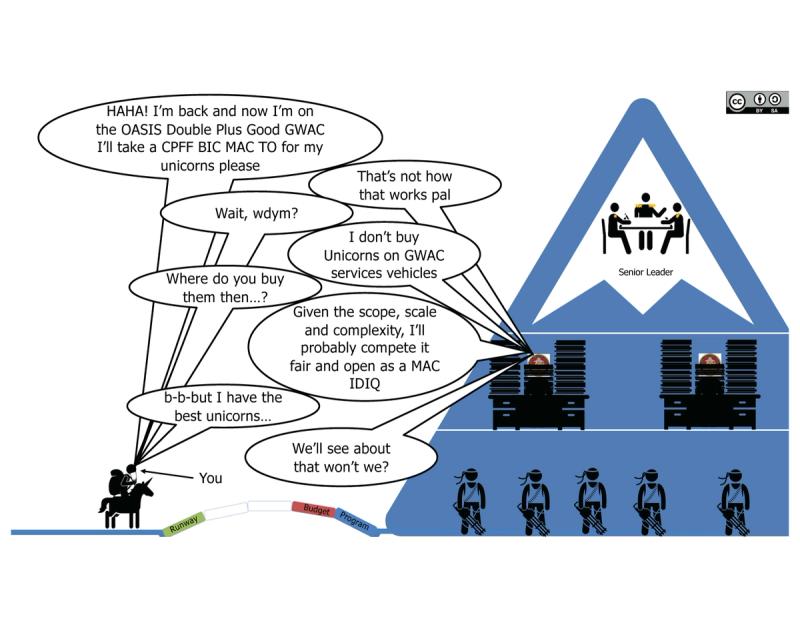

Newbie question: "But why can't I just skip to the end and win the MAC IDIQ CPFF contracts?"

Sage answer: "Because no one trusts you"

There are of course consultant to help you get contracts, many of them do a great job.

In GovCon there's basically a consultant for everything.

You can pay with time or you pay with money, either way you'll pay to win.

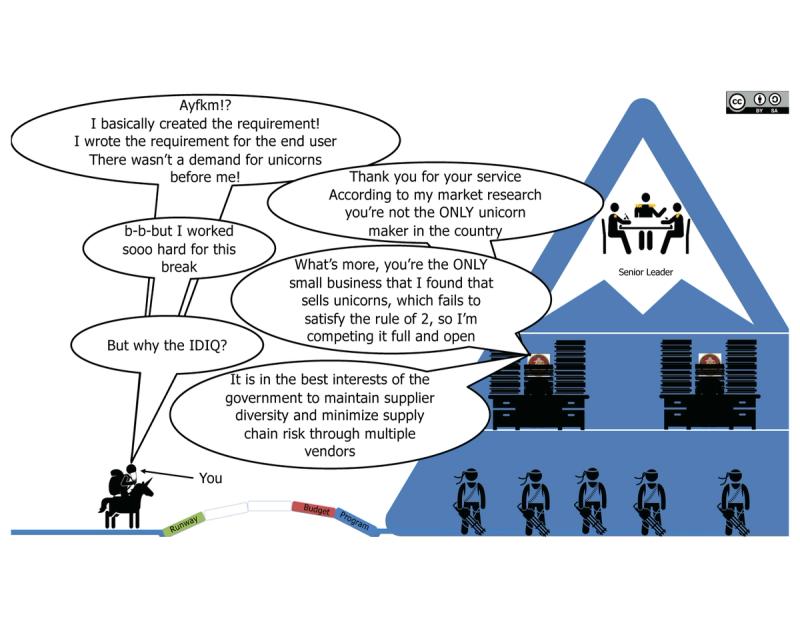

But to win a base award on an IDIQ you usually need GOOD, PRIME past performance (look up CPARS) that is RECENT (last 3-5 years) and relevant (is of a similar "scope and scale"), along with a varied list of GovCon merit badges (more on those later).

If you're new to the game, you won't have these items.

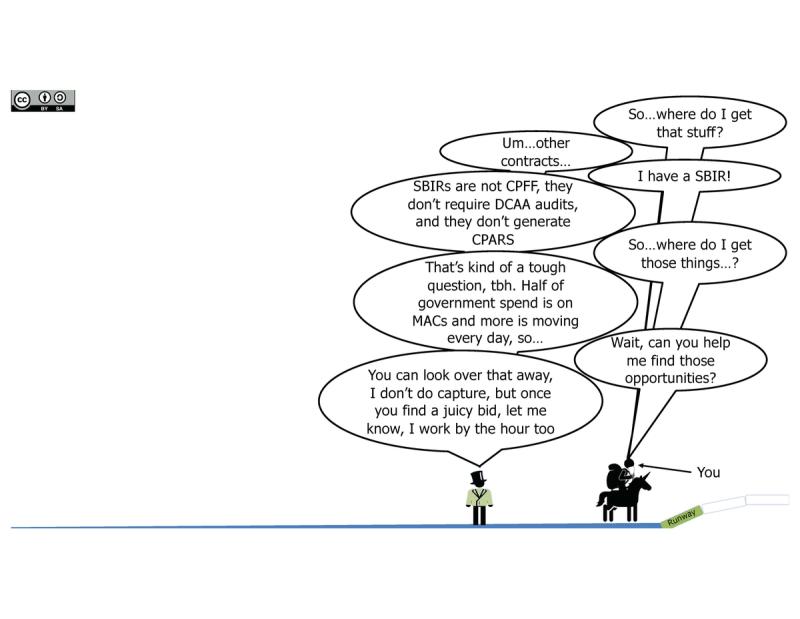

To make things more difficult, subcontract past performance usually isn't relevant(for good reason), and those wonderful SBIRs and OTAs that are such awesome ways to quickly get your technology funded and prototypes fielded...

They don't get CPARS.

And most of them are not of a relevant scope and scale for the major IDIQs.

So what does one do?

How does one get this critical past performance?

You go out to the plains and go hunting for opportunities.

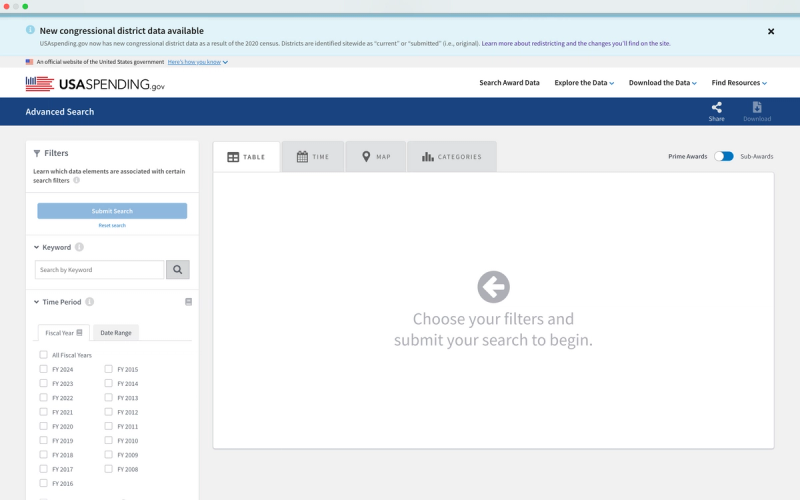

Now keep in mind that only about 50% of opportunities are listed on SAM.gov, the rest are on those IDIQ vehicles.

That said, you can and will find opportunities out there.

It's your job to go get 'em.

Winning these contracts out in the wide prairies of GovCon is one of the few ways to build up your past performance.

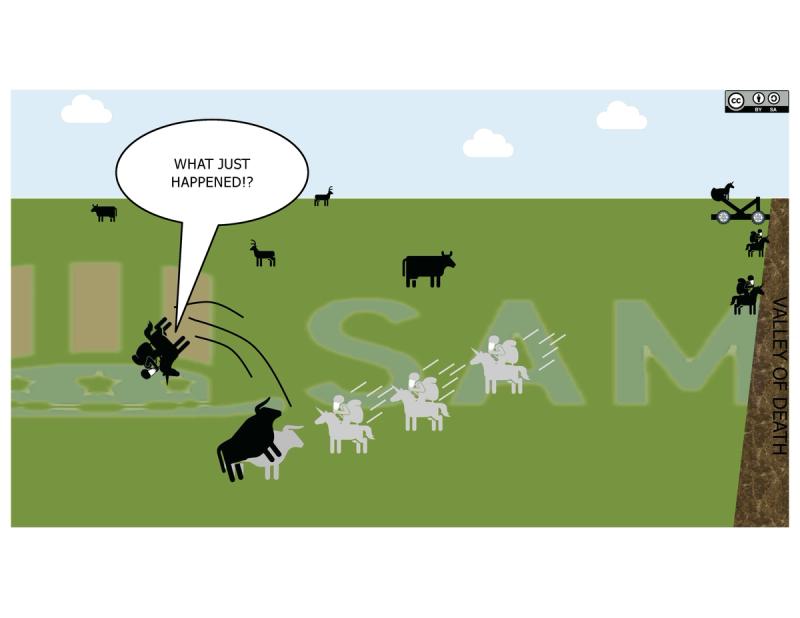

Now, again, trying to skip to the end is almost always a bad idea.

You will likely want to work your way up the food chain.

Trying to jump from a small prototype or delivery contract in the single-digit millions to one that's 10's of millions is quite a leap.

Again, why would any customer trust you to suddenly have the capacity to deliver on a $50M contract when you've only ever delivered on a $5M contract?

Major subs is a way to square that, but we won't get into that here.

When you're working your way up, try thinking about contract sizes in this rough scale:

>1M

1M-5M

5M-10M

10M-25M

25M-50M

50M-100M

100M-250M

Mind you that's executed value, not ceiling or potential value. No one cares how high the contract ceiling is, only the obligated and expended amount.

Headlines that read "<contractor X> won a contract with a potential value of Y" 9 times out of 10 it's either an IDIQ that means almost nothing, or that's the contract ceiling and means slightly more than nothing.

Ceiling: the limit of dollars that can be awarded on a contract

Obligated: dollars actually awarded on a contract

Expended: obligated dollars that are actually invoiced

Expended will be a fraction of the obligated will be a fraction of the ceiling

Bottom line: don't build yourself a reputation for making wild and unwise bids, it's both a waste of time and will likely turn off customers.

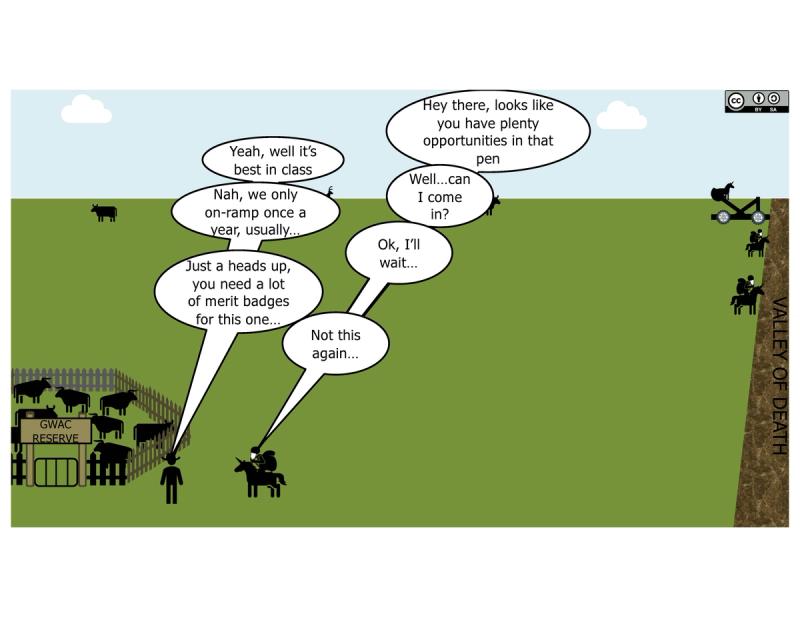

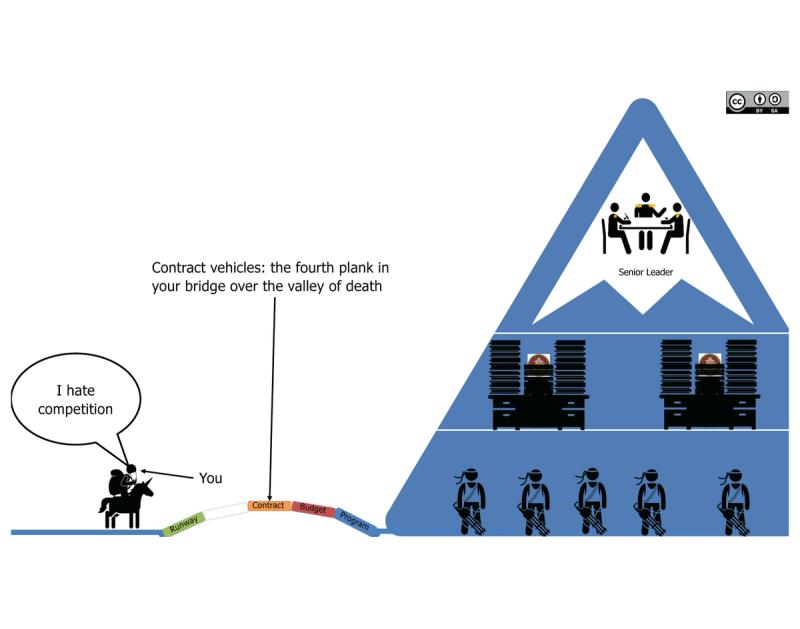

Now, once you work your way up the chain, you may want to go after one of those great Indefinite Delivery contracts.

After all, that's where all the big healthy opportunities are penned up, here's some things to know:

- There are agency-only IDIQs, like DARPA's TASS, that have multiple vendors but only serve one organization.

- There are Service specific IDIQs, like the Army's CHESS for IT stuff that anyone in that Service can (and often are required to) order from

- There are contracts run by organizations that anyone can order from, like EWAAC in the Air Force

- There are multi-agency contracts (MACs) that multiple agencies can order from.

- There are government-wide contracts run by GSA that ANYONE can order form

- Most large IDIQ's have on-ramp periods, every year or two, where they bring on new awardees.

- If you want to on-ramp onto one of these contracts, it pays to prepare well ahead of time, everyone else does.

It's your job to figure out which vehicles are best for your target customers and your product or service.

Because, if you don't you might do what so many companies do; go get on a bunch of irrelevant vehicles that do nothing for your customer.

And staying on vehicles is not a one-and-done prospect, once you get on the vehicle, you have STAY on the vehicle, which often means you have to win, or at least bid on task/delivery orders, or else they'll off-ramp you.

Now, keep in mind, even if you do ALL OF THE WORK, creating a requirements with end users, working it up to the customer, getting them to put in in their budget and then put out a contract to buy it, 99% of the time you will still have to COMPETE for it.

Sorry, that's called equality of opportunity, don't like it, move to Russia.

Newbie question: "but what about sole source?"

Sage answer: "yes let's

Sole source contract happen, sure. But they're hard to pull off and undergo thorough scrutiny (unless you're an 8(a)).

You may think that your things is so special and unique that it justifies a sole source contract.

But, remember that requirements are DESCRIPTIVE not PRESCRIPTIVE, so describe your thing in words, then see if anyone else describes their thing in a similar fashion. If so, then good luck with a sole source.

To put a fine point on it, in order to award a sole source contract, the KO has to write a justification (J&A) that has to be blessed by the lawyers as satisfying one or more of hte following criteria:

Here's the concise list of the specific circumstances under which the U.S. Department of Defense may limit competition in contracting due to various justifications:

- Only One Responsible Source [FAR 6.302-1]

For continuation of a project with a major system or specialized equipment.

When awarding to another source would cause substantial duplication of cost or unacceptable delays.

When unique items are available from a single source or limited sources. - Unusual and Compelling Urgency [FAR 6.302-2]

Emergencies requiring immediate action to prevent significant financial or operational detriment. - Industrial Mobilization [FAR 6.302-3]

To maintain necessary facilities or suppliers in case of national emergency.

To retain services of experts for anticipated litigation.

To preserve critical research, engineering, or developmental capabilities. - International Agreement [FAR 6.302-4]

When a foreign government reimburses the acquisition and dictates the source.

When an international treaty or agreement specifies the solicitation source - Authorized or Required by Statute [FAR 6.302-5]

When law directs procurement from a specific agency or source.

For brand-name items intended for authorized resale. - National Security [FAR 6.302-6]

When revealing the government’s needs could compromise national security. - Public Interest [FAR 6.302-7]

When the head of the agency determines that open competition is not in the public interest for a particular acquisition.

So yeah, good luck with that.

At the end of the day, if you want to get paid, you need to figure out the contracts through which you customer can and will spend their money.

This takes research and probably conversations.

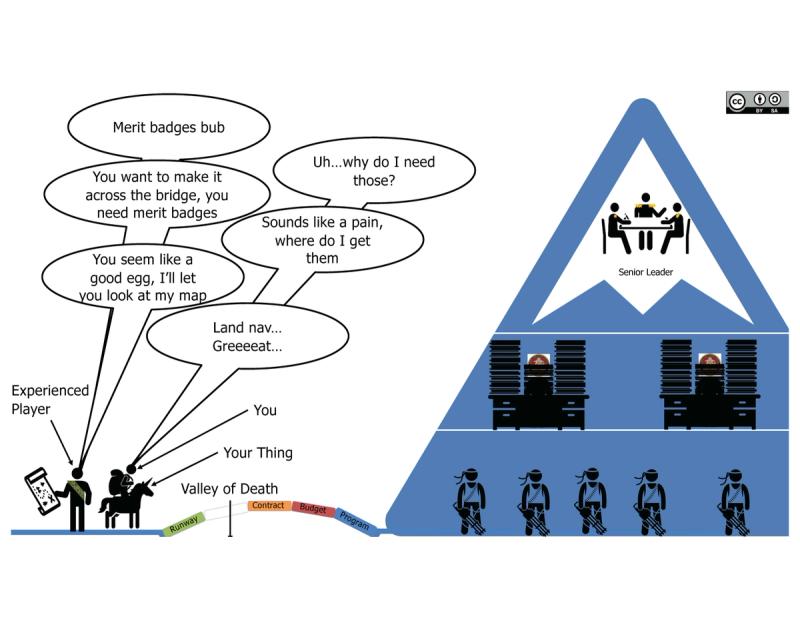

Collect Them Merit Badges

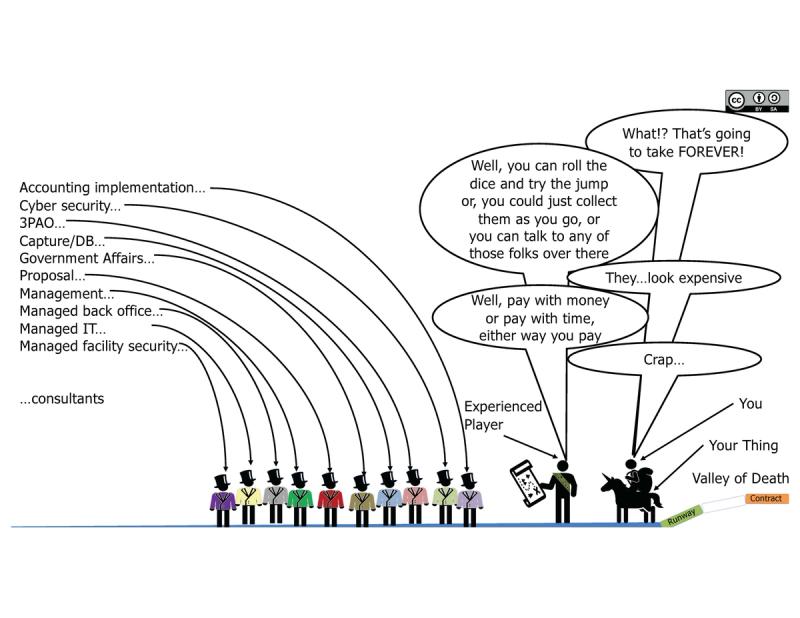

So, there's a lot of regulatory requirements in Government Contracting.

It can be overwhelming.

So many folks throw up their hands and say "it's too hard to work with the government".

But let's reframe the issue.

It all comes down to risk to the government buyers. Can you deliver the goods and services they need without winding them up on the front page of the newspaper.

Remember, regulators don't just sit around thinking up new ways to make your life hell, there's for the rules, maybe everyone forgot why the rule was originally made, but it was almost certainly made because someone screwed up majorly.

You might look over at folks who have been in the game a while and say "how'd you get all those merit badges?!"

"this is impossible"

But it's not, they're cumulative.

You don't need them all at once, but you do need to collect them.

Because here's the thing: merit badges open up opportunities, not having them closes off opportunities.

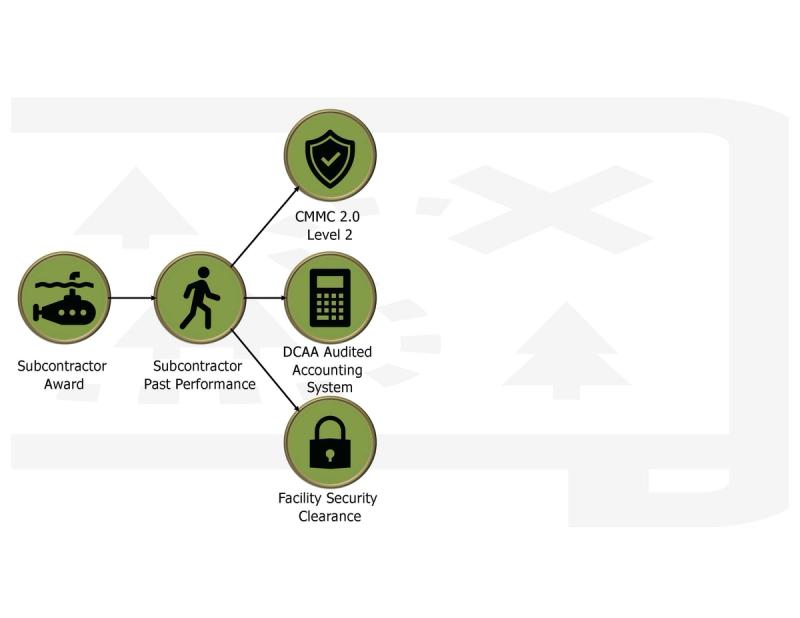

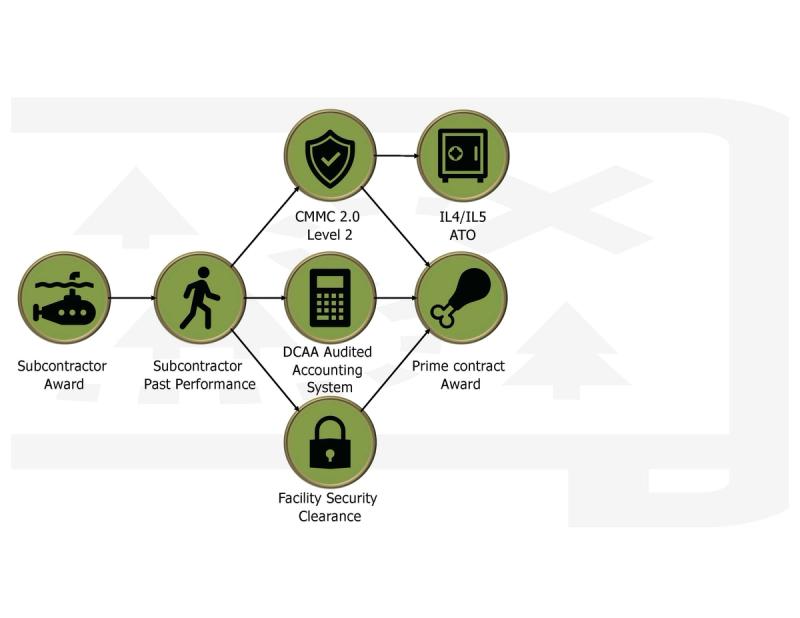

Subcontract Awards