The Secret SBIR/STTR Playbook

What the experts don’t want you to know about winning more SBIRs

Table of contents

Introduction

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program is a highly competitive program that encourages domestic small businesses to engage in Federal Research/Research and Development (R&D) with the potential for commercialization. Over the years, it has become a popular source of funding for startups and small businesses looking to bring innovative ideas to the market. However, like with any government program, navigating the SBIR program has its intricacies, challenges, and best practices.

First, Some Framing

Let’s be honest, not everyone in the government loves the SBIR program, Congress forces them (the executive branch) to do it. It is legally mandated that agencies with research budgets of $100M or more spend 3.2% of that on SBIR projects and agencies with $1B or more per year have to spend 0.45% on STTR projects. Brass tacks that’s $3.2 and billion and $450 million per year respectively each year.

Congress: “you want your R&D budget? you have to spend part of it on these tiny small business projects” Agencies: “ok, fine, if we have to”

Is this a uniform attitude? No, some government folks love the SBIR program. But in reality they don’t have a choice in the matter, they have to spend the money each year.

Avoiding SBIR mills and Expert Consultants

The first recommendation here is to stay away from or at least be highly suspect of SBIR mills and expert consultants, which are often just rent-seekers in this ecosystem. The main goal of the SBIR program is to allocate funds directly for developmental projects, without diluting these funds through intermediaries. It highlights a growing concern within the community, particularly government customers about funds meant for innovation being diverted to other channels that don't directly contribute to the project's objectives.

What is a SBIR Mill?

What are these mythical creatures you ask, how do you spot them in the wild? Well in general terms it’s a middleman company, they generally don’t do the actual research, they keep contact with the technical points of contact and they know where and how to connect with end users so they can win contracts pretty easily. Many of them leverage that connection to go out and find companies whose technology they can propose to SBIR topics. So the mill finds the coming topic or they find the technology and the SEED the topic (more on that later). They then take a fat chunk of the SBIR funding while doing little or none of the work. Other SBIR mills may not use this passthrough practice but simply live off of SBIR money, doing research for the sake of research with little or no actual intention to productize anything that the operational force can actually use.

How do you spot a SBIR mill?

Well, we’re not going to name names, but a good indicator is a company that has more than $50M in SBIR awards and no real products on the open market.

The cool thing is that the data is 100% open on the SBIR website,

“But what about commercialization requirements and reporting, doesn’t that address the problem???” Seriously, be real. If you tell industry which has no interest in making a product that they have to make a product, you know what they’re going to do? they are going to TECHNICALLY make a product, and then go right back to doing what they want.

Why Do They Even Exist?

Let’s be fair, and this is for you government readers everywhere:

MAKING AND SELLING PRODUCTS IS HARD.

Like, REALLY hard. So you want your cake and to eat it too, you want these research houses to do cutting edge TRL 1-6 research, then you want them to turn around and stand up a product development, sales, advertising, customer service, customer delivery, logistics, and help desk shop too!

With what? That $1M Phase 2 award is maybe 5 people’s salary, tops. Oh, and the likelihood of getting a Phase 3 contract is somewhere between hopeless and highly unlikely, so what you are effectively asking is for a private enterprise to:

- Come up with an original idea for solving YOUR problem

- Solve that problem with $50k-$1.5M

- Figure out how to sell that product to you, with little or no help from you (more on that later)

- And do every part of #3 with no additional resource, except maybe $5 grand in TABA funding that we are supposed to pay to your anointed consultants (more rent-seeking)

Don’t hate the players, hate the game, but don’t be shy about calling the balls and strikes.

Connecting with End-Users:

It's crucial to engage with end-users early in the process. This not only provides valuable feedback but also demonstrates market demand, which is essential for SBIR projects. According to a Forbes article, understanding your customers is a cornerstone in marketing and project validation, which can significantly enhance the potential success and impact of your SBIR project.

The three players in the government game

There are three main important stakeholders on the government side of the technology development and capability acquisition process:

- End-users - doctors, scientists, pilots, infantrymen, immunologists, border agents, submariners, maintainers, logisticians, etc. These people do things. They deliver the functions of government or support those who do, full stop. They have operational problems, capability shortfalls. These folks have the problems that your technology should solve, full stop.

- Program Managers/Acquisition Professionals/Technologists - these are typically the Technical Points of Contact (TPOCs) in the SBIR program. These folks don’t have the problems, they have to deliver the capabilities (read: technologies) that SOLVE the problems of the end-users. End-users are these peoples’ customers. Paradoxically if you sign a contract, these typically contractually YOUR customers. so YOUR customers have customers who problems you are actually solving. Wrap your head around that one, int’s important.

- Senior leaders - these are the folks whom you will likely never meet. But, they almost always have strategic visions, plans, strategies, roadmaps, etc. Often, the things on those sundry vison documents directly affect the end-users, because the end-users have to actually fulfill said vision. Visions are almost always of the future, where their organization (read: end-users) will be doing something they are not doing today. Well, to do that new thing they will need new capabilities - insert your technology. Is this always the case? No. Sometimes your technology is solving the challenges created by the last senior leader’s vision, either way, if end-users were being asked to do something they could already do, they wouldn’t need your new technology.

So you see this is a cycle: senior leaders have a vision, they require end-users to do something to fulfil that vision, that creates capability gaps, which Program Managers are obliged to fill, with your technology.

End-user Endorsements:

When pursuing a SBIR topic, particularly Air Force SBIR projects, securing endorsements is a huge contributor to improving your probability of a win, it’s like having a stamp of approval or support for your project. These endorsements are seen as a level of vetting and support that can greatly enhance the credibility and potential acceptance. Honestly, this should be intuitive at this point, if your customer is the Program Manager, and their customer is the end-user, then getting a stamp of approval from their customer should strongly influence the decision of your customer. From another perspective that may be less apparent, technology transition is very difficult, so think of this step making the transition path for your proposed technology easier on the PM. The easier you can make it for the government to say “yes”, the more often they will do so.

“But where do I meet these end-users?” 😩

Great question, do your own homework. There’s a plethora of engagement events all over the place all the time. Start at the SBIR sites for your chosen target customer, they all have them, and look for events. Failing that, reach out to the TPOCS, failing that look for relevant industry events.

Government Support Post-award

After receiving the award, it's important to temper expectations of extended support from the government. The Project Managers (PMs) overseeing these projects have many responsibilities, and your SBIR project is just one of them (and a small one). As per the SBIR Phase II Guidelines, the primary goal is to move towards commercialization, with the government's role being more of a facilitator through funding rather than ongoing support. So again, make it easier on them, be proactive, take responsibility and initiative.

So what do I do???

In short, be proactive. I know it’s a lot of extra effort, but let’s look again at the triangle here: End-User ↔ Program Manager ↔ Senior Leader

If you want to be proactive you should do some research and find way to approach these three groups. There a myriad of end-user engagement events (in DoD in particular) that you can sign up for. Things like SOF Technical Experimentation, Trident Spectre, Project Convergence or DHS SVIP. Many of these events require government “sponsorship”, which means your TPOC will have to help you sign up. But, you can be proactive, you can go out and find these events, you can ask your TPOC if you can attend. More often then not, if you go to your TPOC and say “hey, we found this relevant test and evaluation or demo event, we want to try and get in front of your customers, will you sponsor us?” the answer will be “sure”.

Now, lets be clear, if you’re doing a phase 1 that will only result in a white paper, you have no need to go to these events to be a demonstrator, but you can still sign up to be there, engage with end-users, and learn about the tangible aspects of operational challenges.

Engage with the TPOC Early

It's a good idea to engage with the Technical Point of Contact (TPOC) DIRECTLY over email and do it early on, like as soon as the prerelease drops. This communication can provide valuable insight and understanding that may not be available later when topics go live. According to the DoD SBIR/STTR Help Desk, early engagement often brings clarity and helps align your proposal with the program's expectations. Important note: be prepared to ask questions that will clarify your proposal and sharpen your approach.

Important note: they can’t answer questions that would hint towards directing your proposed approach, so steer clear of “would you be interested in <insert specific technology approach here>?” but they may be open to answering something like “have you tried a <insert technical approach> in past research?” or “are there <insert technology> aspects or considerations” you could even to try an inverse answer “are there policies or integration barriers to the usage of <insert technology>?”.

Bottom line: reach out, be prepared, and be smart, they’ll probably only give you 30minutes, so have an idea of what you’re going to propose before you reach out, and then use the call to INDIRECTLY validate or sharpen your approach.

Here’s the Secret of How the Game is ACTUALLY Played

So you think that TPOCs come up with these problem statements from thin air? Yes, some of them do. But the folks who really play this game seed the requirements.

What is seeding you ask? Well imagine you know the strategic vision of an organization because you read the senior leader’s vision document. Now imagine you also know some of the TPOCs, either because you previously bid on/won a SBIR contract and you know what kinds of work they do, who their customers are, etc. Now further and finally imagine that you see the vision document, you imagine a problem it creates for end-users that your technology can solve, and you type that up and bring that PROBLEM to the TPOC (program manager, etc).

Now remember, these TPOC have to do this SBIR thing, they don't have much choice in the matter, so if you show up with a capability shortfall that you observed in their customer (end-user) base that aligns with their senior leader’s vision, well then you just solved a problem for them. Now they don’t have to spend their own time coming up with a topic to submit, they can just use yours. When the topic (seed) you planted ends up being selected and published, it is a money tree growing for you to harvest. This is the way the game is really played, this is the game the SBIR mills play.

Now, planting season is key, you don’t want your topic to be buried under a pile of paper because you tried planting it at the wrong time. The SBIR process, just like agriculture goes in cycles, here’s how it generally works:

- There is typically an agency office that handles the overall program - think DoD SBIR, or DHS S&T

- Below them there is usually an organizational office that manages the process - think Office of Naval Research

- Below them there is typically a Point of Contact at each major organization - think NAVSEA or Team Subs

- Below them is typically the PMs who have programs and customers and way too much work to do

So here’s how it works each cycle:

DoD SBIR does a call the all of DoD → ONR does a call to all of Navy → NAVSEA does a call to all sub orgs → sub org POCs call to all PMs

PMs send their topics to their org POC → they consolidate and maybe a down-select → Org POCs send them NAVSEA → they consolidate and maybe a down-select → NAVSEA sends consolidated topics to ONR → they consolidate and maybe a down-select → ONR Sends to DoD SBIR → DoD SBIR wraps them up and pushes out the quarterly Broad Agency Announcement.

There are caveats, DARPA has special authority to do SBIRs out of cycle, other probably do too, but above the general process.

So what does that mean to you? Look at all of the points where you can slide in and influence the topics that are going to be published. These folks are not hard to find, it’s usually in their job title on LinkedIn, they also tend to host industry days and webinars and all of the other typical outreach events. Failing all of the, you can always go through the local small business advocate.

Budgeting

It's a good idea to bid only what's necessary for the project, DO NOT BID $149,998 for a SBIR phase 1 when the max is $150K. From your point of view this makes sense (government readers tune in here):

- You need to make payroll, and more top line means more bottom line

- Dollars = hours of work, its a linear function, so the more hours you bid the better product you can produce and increase the likelihood of getting the next phase, right? After all, you can ALWAYS do MORE research.

- They wouldn’t make a limit if they didn’t expect us to use it, right

Not necessarily, think about it from the government perspective (industry tune in here):

- You’re a PM who has technology challenges to address, and you (or your organization) have a SBIR budget, so if you can make one large bet or two smaller bets, which one are you going to do?

- If you’re a PM and one company says they can solve your problem or answer your question with $1M and another says they can do it with $1.49997M, which one do you trust more?

- If the company is going to the limit on their bid now, what happens when they eventually bid on follow-on work, are they going to try and squeeze every time out of you when it’s coming out of your real R&D budget.

- If a company comes in with a bid that’s a hair’s breadth from the limit, did they really think through the budget, or did they just back in to the number? Probably the latter.

Bottom line, as the guide on SBIR budget suggests, a well-thought-out budget reflects a better understanding and planning of the project, which is always more favorable during the evaluation process.

Relying on Multiple SBIR Awards

While some companies have relied solely on SBIR awards, it's not considered a sustainable or reputable business model. The ultimate goal is to transition to a self-sustaining model. There are numerous SBIR Success Stories that have successfully transitioned from dependency on SBIR awards to establishing a strong market presence. Every time you get an SBIR award, assume that you won’t get another one, and act like it.

While we’re on the topic, lets talk brass tacks, if you’re going to bid on a SBIR topic and you have no intention of commercializing what you’re proposing DON’T BID!

Seriously, do everyone a favor and don’t put in a bid if you don’t have any intention of fulfilling the purpose of the program which is the following:

Invest in early technology so that companies don’t have to solely rely on outside investors so that the companies can commercialize said technology so that the government can then buy it.

If you don’t commercialize the technology (because you’re just looking for the easy cash) then the government can’t buy it and in turn realize the return on their investment.

Now let’s be clear, just because you plan and have every intention to commercialize your technology, there are a variety of reason why that may not happen; the technology doesn’t pan out, you can’t fine product-market fit, etc.

However, there is a difference between planning and failing to commercialize and planning on failing to commercialize.

Define “Commercialize”

Commercialization does not necessarily mean making a commercial product that appeals to the private market and has a shot at trending on Amazon. Commercialize simply means turning your research into a thing someone can buy, ideally a government someone. If your technology is software, this could be as simple as setting up a Shopify page with a download source. Not to trivialize license management and customer service, the point is that “commercialize doesn’t mean you need a production facility and fully sales staff - start small if you have to. But, if your plan is to make a breadboard bench-top prototype and then go “back to the well” for another traunch of R&D money from government to keep your research going, with no intention of putting that prototype into a product, you are a SBIR mill.

One final note: if your “commercialization model” is to perpetually do research and offer to “license” the technology for other companies to productize, you’re a SBIR mill.

Transition Planning

Having a clear plan to transition your SBIR project into a marketable product is crucial. Government funding is meant to serve as a springboard for your innovation, not a perpetual support system, as we discussed above. So how do you really go about this, how does one plan to do something they have never done before? Good question. Aside from the mandatory commercialization plan slides that some SBIR topics require, there’s not a ton of insights on how to actually lay one of these plans. We’re not Silicon Valley-philes per se, but those folks do have a lot of reps on turning ideas into products, and probably about the same success rate (~3%) as SBIR program. Y Combinator has a pretty good and free Startup Bootcamp with a great module on finding “Product-Market Fit”. Stretch your mind a bit and replace all reference to customers with your TPOC/PMs customers and it should make sense. If you can’t make your product fit with that market of customers then you’re just as lost as the 97% of valley startups who fail.

For the basics Try thinking about this:

- What are you building? Is it a full-up system (think iPhone), is it a subcomponent (think better iPhone camera), is it software (think iPhone app), is it an enabling technology (think 5G waveform that the iPhone uses to connect to towers). It has to fit somewhere in the technology ecosystem, and more importantly the capability ecosystem. So be clear up front what it is you’re actually looking to build. This will help you be very clear about HOW you need transition it. If you can’t or don’t want to build an entire iPhone, then you’re going to rely on other people’s technology (and possibly customers, contracts, IP,

- Who buys it, what’s your Total Addressable Market (TAM)? We see a lot of people building for cool folks like Green Beret’s and Navy SEALS, why not, they have cool missions and cool problems. But, how many are there? Like a few tens of thousands. how many regular Army Infantry Soldiers are there? If you’re going to build a product, even if you do it under a SOCOM SBIR, wouldn’t you build it to address that larger Army market? the same goes for every other Executive Branch Agency, don’t JUST focus on your TPOC/PMs customer. When you’re talking about transition planning, broaden your scope and see who else can use your technology, including the private market.

- HOW DO THEY BUY IT? This is critical in the government market, HOW they buy is as important as what they buy. It is (sadly) completely plausible that a customer could want your technology but they are only allowed or able to buy your type of technology on a particular vehicle, or using particular funding, etc. If you want to be successful you need to find this stuff out, your TPOC can probably explain some of this to you if you ask, so ask.

- Again, make it easy for your TPOC to help you help your TPOC. Your TPOC/PM wants you to transition your technology, they get kudos for you doing so, they may not know how best to transition your technology, after all they are probably technologists, not acquisition experts. If you can map our a transition path and they can write a letter, memo, endorsement, email, or make a phone call, that will help you transition, they’ll probably do it.

Utilizing SBIR as a Customer Engagement Tool

This may be an overly obvious opinion at this point, but just to put a fine point on it: an SBIR contract should be seen as an opportunity to build relationships with potential customers. If you look at it as a paid opportunity to build a product and actively sell it to a potential customer base, the whole program looks different. Active business development is encouraged to maximize this opportunity. If you look at a SBIR as fee-for-service development for a government customer then you're more apt to expect something that likely wont come. But if you likely it to the commercial model of coming up with an idea → seeking angel investment → finding product market fit → grind on sales efforts → try to sell your product and turn a profit, consider the SBIR program an angel investor who doesn’t take equity. You still have to do all the other steps to be successful, but you don’t have an investor breathing down your neck to “go to market” so they can recoup their investment.

Keep Bidding:

Persistence in bidding is a virtue in the SBIR arena. If your initial proposals don't make the cut, refine and resubmit them or explore other topics. Keep track of the TPOCs you work with, see if you can reengage with them in the next cycle. There are few challenges that cannot be overcome with more persistence and effort.

What About STTRs

The Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program is intended to foster collaboration between small businesses and research institutions. It's tailored to convert scientific discoveries into commercial products, a step towards propelling the U.S. into the forefront of technological advancements.

First - What is STTR Really For

The STTR program is really there to try and pull research out of the Universities and get it into products. Universities CAN’T make products, the best they can do is “spin out” a startup with one of their researcher professors. Imagine how often that happens. So, if you’re a company diving into STTR, be clear about your role: productize the research!

What sets the STTR program apart is its emphasis on partnerships. It requires small businesses to work with nonprofit research entities, creating a synergistic relationship. This collaboration not only augments the innovation capacity of small businesses but also facilitates the transition of academic discoveries into market-ready products.

Now, let’s draw a parallel with the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. While SBIR is a significant funding source for small businesses, it has a different set of dynamics compared to STTR. Here’s a closer look at how STTR stands out:

- Fostering Collaboration: The STTR program is grounded in collaborative research, making it a conducive environment for shared innovation. Unlike SBIR, which doesn’t necessitate partnerships, STTR brings a communal aspect to the R&D process.

- Accelerating Technology Transfer: STTR is designed to fast-track the transfer of technology from the academic realm to the commercial sphere. This dimension of technology transfer is less accentuated in the SBIR program.

- Access to a Wealth of Intellectual Resources: By partnering with research institutions, STTR grants small businesses access to a rich reservoir of intellectual resources and cutting-edge research facilities, a feature less prominent in the SBIR program.

- Commercial Transition of Academic Innovations: STTR serves as a gateway for academic innovations to find their way to the market, ensuring that valuable discoveries don’t just remain confined to the labs.

- Broadened Funding Spectrum: With its dual focus on innovation and technology transfer, STTR expands the funding horizon for applicants, unlike SBIR’s more singular focus on technological innovation.

Second - Your Odds of Winning Quadruple

There are simply fewer STTR funds, there are also a fraction of STTR proposers. Why? because it’s harder, you have to find a topic, find a University, make a teaming agreement, come up with a joint approach, bid together and THEN ideally work together. So much easier to just go it alone.

But, because there are fewer STTR proposers, your odds of winning an STTR topic are generally 4x that of an SBIR, because there are just 1/4 of the proposals.

Third - There’s Safer Bets

Look up Universities who do STTR work, and look at what kind of research they’ve done. Match the tech to what you want to research and back into who to call. Keep in mind that Universities have contractual idiosyncrasies based on their State laws, bylaws, etc. Also, Universities are large bureaucracies that may take longer to process paperwork than companies with pressing profit motive, so plan extra time for admin matters.

Summary

Navigating the SBIR/STTR program requires a blend of innovation, strategic planning, early engagement with relevant entities, and a thorough understanding of the budgeting and proposal process. It's a competitive space where persistence, accurate budgeting, and a clear transition plan towards commercialization are highly regarded. The discussion accentuates the importance of direct engagement, be it with end-users or Technical Points of Contact (TPOC), and underscores the necessity of viewing SBIR awards as a stepping stone rather than a final destination. Through a meticulous approach, grounded in the insights provided, small businesses can significantly enhance their prospects of securing SBIR awards and subsequently, achieving successful commercialization of their innovative solutions.

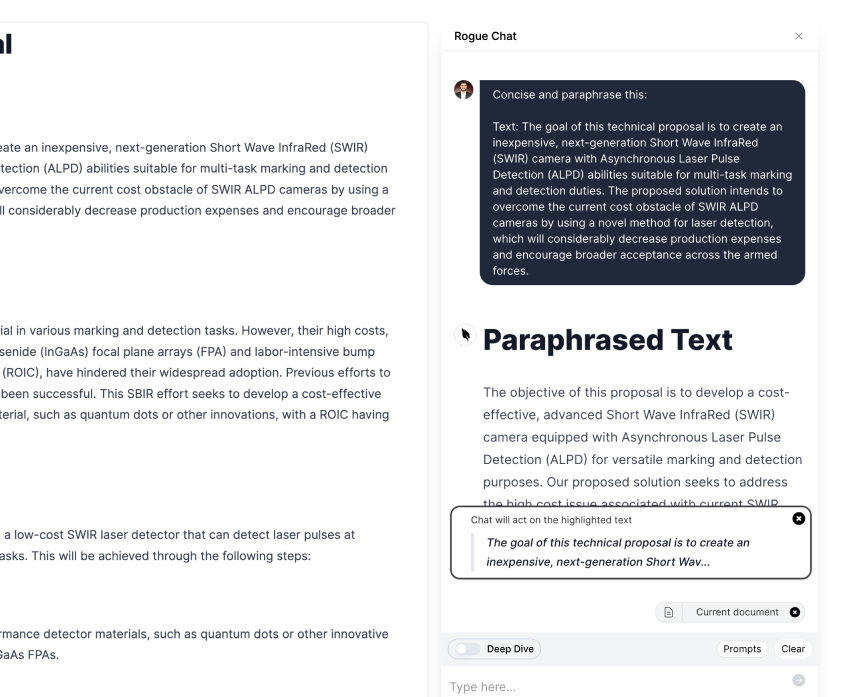

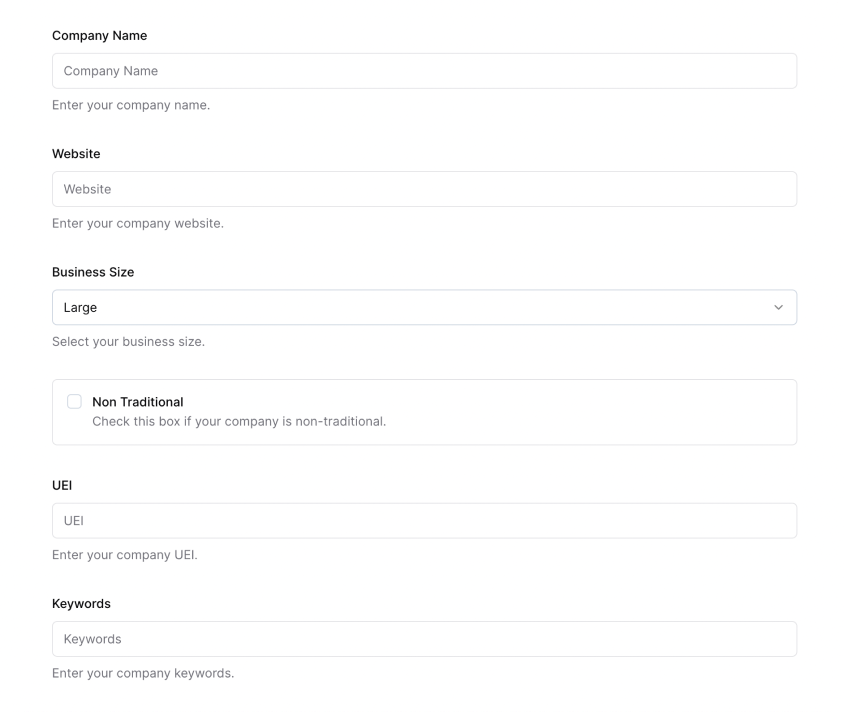

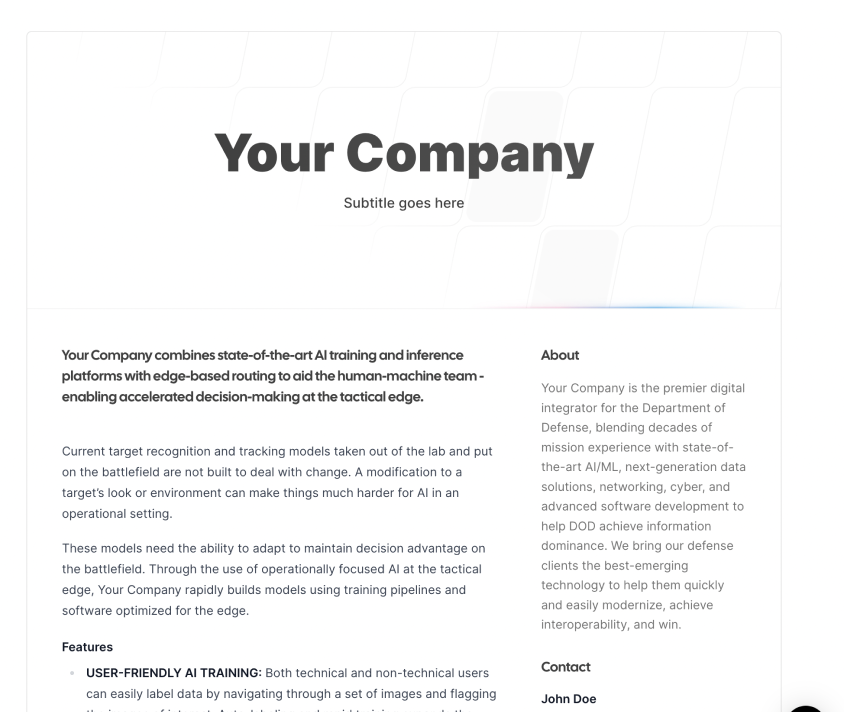

Sign up for Rogue today!

Get started with Rogue and experience the best proposal writing tool in the industry.